The Republican Party’s economic policies have grown so corrupt and regressive as to be literally unbelievable. In focus groups, Democratic operatives have found that swing voters will often dismiss simple descriptions of the GOP’s self-avowed fiscal priorities as partisan attacks — after all, how could any major political party actually favor slashing Medicare benefits to lower taxes on the one percent?

Alas, a plain recitation of the Trump administration’s agenda on student debt is sure to strike many Americans as even more implausible.

But before we examine the president’s (absurdly corrupt) “college affordability” policies, let’s take a quick tour of the crisis that he inherited.

In the United States today, 44 million people carry $1.4 trillion in student debt. That giant pile of financial obligations isn’t just a burden on individual borrowers, but on the nation’s entire economy. The concomitant rise in the cost of college tuition — and stagnation of entry-level wages for college graduates — has depressed the purchasing power of a broad, and growing, part of the labor force. Many of these workers are struggling to keep their heads above water; recent research suggests that 11 percent of aggregate student-loan debt is more than 90 days past due or delinquent. Other borrowers are unable to invest in a home, vehicle, or start a family (and engage in all the myriad acts of consumption that go with that).

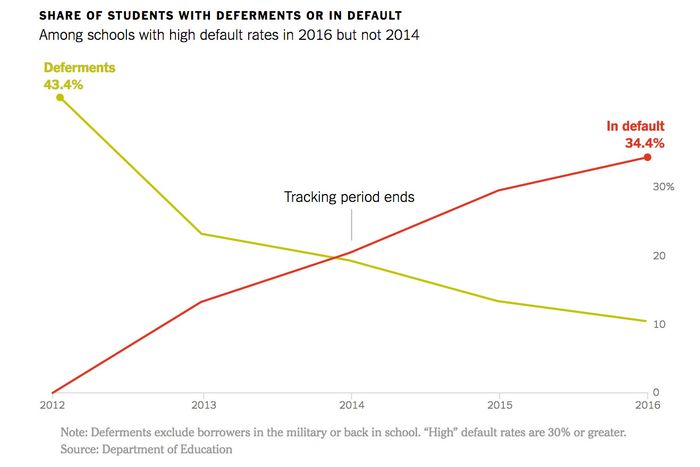

The full scale of this disaster is still coming into view. Just this week, the Center for American Progress (CAP) revealed that official government statistics have been hiding the depths of our student-debt problem. Federal law requires colleges that participate in student-loan programs to keep their borrowers’ default rates under 30 percent for three years after they begin repayment. But once those three years are up, federal tracking ends. Using a Freedom of Information Act request, CAP’s Ben Miller secured never-before-released data on what happens to default rates after Uncle Sam stops watching.

He found that many colleges (especially for-profit ones) have been artificially depressing their default rates during the three-year window by showering their borrowers in deferments — essentially, special allowances that empower debtors to temporarily stop making debt payments without going into delinquency. After the three years are up, the deferments disappear — and the default rates skyrocket.

Just about all of America’s institutions of higher learning are complicit in this sorry state of affairs. But for-profit colleges have been far and away the most malevolent actors. The entrepreneurs behind such schools looked at the masses of Americans struggling to claw their way up the socioeconomic ladder — and then at the giant stack of federal student loans available to such strivers — and hatched a plan for “disrupting” the higher-education market: Whereas many traditional universities had inefficiently concentrated their capital on research centers, student services, and faculty, for-profit colleges recognized that an ounce of marketing was worth a pound of quality instruction. Providing students with a good education and competitive job opportunities is a difficult, time-consuming, capital-intensive endeavor — but leading students to believe that you can provide them such things could be done with a few targeted investments in video and graphic design.

Through this innovative strategy — and a boom in the supply of desperate, underemployed Americans following the Great Recession — for-profit colleges quickly claimed an outsize share of federal student dollars. In 2014, 13 of the 25 colleges and universities where students held the most education debt were for-profit institutions. Collectively, students who attended such schools held $229 billion in debt.

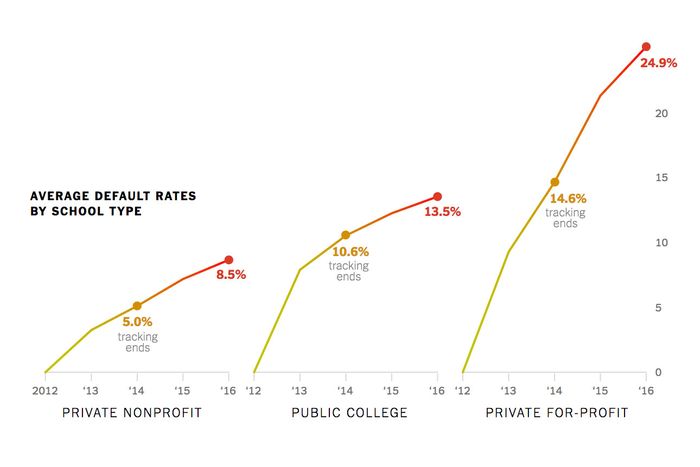

And they were getting little bang for their buck. As shown above, default rates among students who attended private, for-profit colleges have run three times as high as those at private, nonprofit schools — while the former’s graduation rates are more than 30 percent lower.

In light of these facts, the Obama administration concluded that it was actually a bad idea for the federal government to subsidize an industry that specializes in the production of useless diplomas and debt-burdened Americans. So, in 2014, the Education Department established new rules that denied taxpayer-backed loans and grants to colleges whose graduates routinely failed to meet a minimum debt-to-income ratio. In other words, if your school excelled at using sleek advertisements to get students through the door — but failed to place your graduates in jobs that pay enough to make their student debts sustainable — you wouldn’t get to live off taxpayers’ money anymore.

The Trump White House took exception to this policy. In its view, denying government subsidies to businesses that engage in massive fraud is a tyrannical violation of “free market” principles. Thus, Education Secretary Betsy DeVos launched a plan to throw out the gainful-employment rules earlier this month. In making the case for her rollback, DeVos suggested that the Obama administration had unfairly targeted for-profit institutions for scrutiny — a claim ostensibly substantiated by the fact that dozens of for-profit colleges have opted to close (rather than submit themselves to accountability) since the rule went into effect. According to the Education Department’s own estimates, ending Obama’s lending restrictions to for-profit colleges will cost the federal government $5.3 billion over the next decade (as the number of student-loan borrowers who are forced into default will skyrocket).

As DeVos works to funnel more taxpayer money to low-performing, for-profit colleges, she’s cracking down on federal-student-loan forgiveness. The secretary believes that the Obama administration’s standards for forgiving a student’s debts (on account of financial hardship or false advertising) were far too generous — explaining, under “the previous rules, all one had to do was raise his or her hands to be entitled to so-called free money.”

Meanwhile, DeVos is diligently working to ensure that banks and loan servicers remain entitled to every penny that they can squeeze out of student debtors through fraud and abuse. (In a bizarre coincidence, DeVos has close financial ties to a debt collection agency that does business with the Education Department.)

In 2017, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) sued Navient, America’s largest servicer of federal and private student loans. The watchdog agency found that Navient had worked to keep debtors from repaying their loans too quickly (so as to maximize the interest payments they could skim) by “providing bad information, processing payments incorrectly, and failing to act when borrowers complained.” The loan servicer had also (allegedly) “illegally cheated many struggling borrowers out of their rights to lower repayments.”

DeVos has done everything in her power to undermine that lawsuit. Last September, her department announced that it would no longer share its student-loan data with the CFPB, arguing that the regulator had grown “overreaching and unaccountable.” In reality, the move rendered America’s largest student-loan companies unaccountable by making it impossible for the CFPB to conduct routine oversight of their businesses. DeVos proceeded to prevent Navient from giving the consumer bureau access to the documents that the latter would need to determine whether the loan-service provider’s practices had been above board.

On Monday, the CFPB’s top regulator of the student-loan industry resigned in protest. In a letter to the agency’s interim director, Mick Mulvaney, student loan ombudsman Seth Frotman wrote, “Under your leadership, the Bureau has abandoned the very consumers it is tasked by Congress with protecting. Instead, you have used the Bureau to serve the wishes of the most powerful financial companies in America.”

Frotman’s assessment surely reads like a partisan jab. But it is an objective summary of White House policy.

The Trump administration looked out on a student-debt crisis that was financially ruining millions of young people, sapping economic growth, and allowing scam artists to grow rich off taxpayer funds — and concluded that the core problem with Obama’s college-affordability agenda was that it had failed to hold students and federal regulators accountable for their abuses of loan servicers and for-profit colleges.

Students might still find a way to be our nation’s future — but kleptocracy is its present.