At 2:30 on February 14, David Hogg was not yet a spokesperson for radicalized young America or a renowned media savant or a resistance fighter or, to some, the encapsulation of everything terrifying about where the country is going, but a high-school senior crouched in a dark classroom while a gunman with an AR-15 ranged beyond the walls of his hiding place, slaughtering 17 people in six minutes. In the quiet aftermath, when the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School had stopped but before the SWAT team had given the all clear, the 17-year-old debate geek did what first came to mind: He detached himself from the situation by turning on his phone’s video recorder and, in a perfect simulation of the news correspondents he had watched in his bedroom for years, narrated the events that had just taken place. To an imaginary audience, Hogg explained that he, like many of his classmates in Parkland, Florida, had initially thought the massacre was a drill. “And then we heard more gunshots,” he said somberly, still in a crouch, his face in shadow, “and that was when we realized, This was not a drill.”

Like so many young men in so many foxholes before him, Hogg discovered in himself a powerful drive not to leave this Earth without making a mark. “We really only remember a few hundred people, if that many, out of the billions that have ever lived,” he told me at his house in a gated community in Parkland, ten days after the shooting. “Is that what I was destined to become?” Hogg was home alone that day, checking his phone and keeping company with Tater, the family terrier (allergic to grass but fond of tangerines and bananas), and he struck me as surprisingly composed. After the shooting, he had met up with his father but then driven himself home. That’s when he lost it, alone in the car, screaming “Fuck!” again and again at the top of his lungs and hammering his fists on the dashboard. By the time he got to his house, he was calm enough to send his video to the Sun-Sentinel, the newspaper where he worked as an intern. “I had the exclusive for about six hours,” he told me.

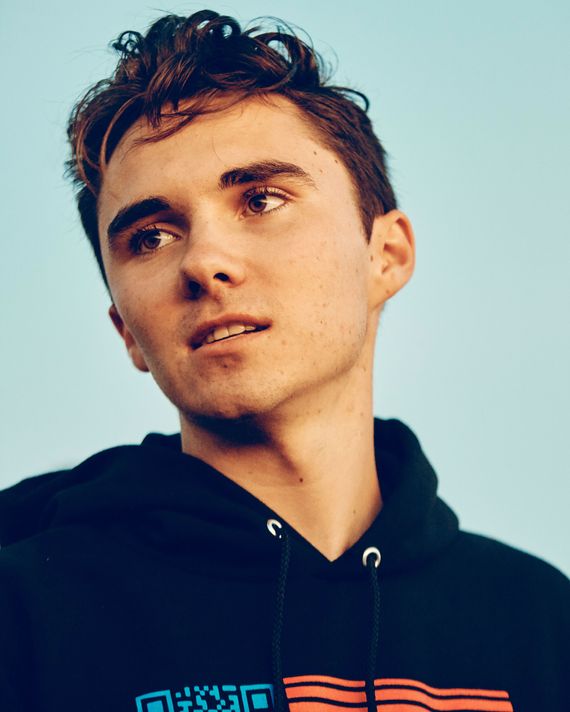

Hogg understood that he was living in a historical moment. Later that evening, he shouldered past his father, who was blocking the door, and biked back to school, where he offered his eyewitness account to the first television producer he saw. The segment with Laura Ingraham aired live at 10:05 on Fox. It is remarkable to watch — Hogg with his stoic poise, his David Byrne cheekbones and wide-set stare, his grave expression and small impatient nods of understanding, narrating the day’s atrocities. But it’s most memorable for its final moments, when he refuses to allow Ingraham to offer her condolences or to get off the air. “Can I say one more thing to the audience? I don’t want this just to be another mass shooting. I don’t want this to be something that people forget.”

By 6 a.m., to his parents’ astonishment, Hogg was in an ABC News van riding back to school, preparing to interview with George Stephanopoulos. Just past nine, on MSNBC, he was smoother now, more assertive and armed with facts. “Everybody’s getting used to this, and that’s not okay,” he told Stephanie Ruhle. He referenced statistics from Everytown for Gun Safety: “There have been 18 more mass shootings than there need to be this year at schools. It needs to come to an end.”

Instantly he was absorbed into the crew camped out at the house of a schoolmate named Cameron Kasky, a loose association of Parkland juniors and seniors who saw the shooting with the moral clarity of revolutionaries. Soon the group was operating under a hashtag, #NeverAgain, and planning a march on Washington. Hogg was so obviously an asset, a connoisseur of news cycles and sound bites, with the ability to hoover up facts and figures like his idol John Oliver and then spew them in angry torrents before the cameras. When Anderson Cooper asked Hogg if banning bump stocks was a good idea, his answer was succinct: “Absolutely, but that should have been done after 50 people were slaughtered in Las Vegas.”

Hogg was good on TV — great, even — and in the marathon of coverage that followed the Parkland shooting, he honed his persona. Angry, edgy, righteous, relentless, he was the warrior who would take anyone on and refused to be knocked off message. The White House called to invite him to the president’s “listening session” on guns, and he hung up on them. He told this to Bill Maher on his HBO show, physically leaning across his friend Kasky and into Maher’s face to make his point. “I ended on this message with them: We don’t need to listen to President Trump. President Trump needs to listen to the screams of the children and the screams of this nation.”

Emma González, also a senior, was friendly with Hogg from the previous year, when they collaborated on Project Aquila, an experimental weather balloon for astronomy club. (She tracked the data; he was the documentarian.) After the shooting, they became figureheads of what has felt like a natural phenomenon: a groundswell, a tidal wave, perhaps something more lasting than the grief-and-outrage cycles that accompanied previous mass shootings. They were an irresistible pair. González spoke to the cameras and crowds with transparent emotional intensity, bringing the nation to tears with her heartbreak and fury. Hogg, also intense, was sharper, more aggressive, and spoke more strategically. His Twitter following exploded into the high six digits, hers past seven. Mostly, she drew adoration. He was easier to hate. Right-wing conspiracy theorists accused him of being a “crisis actor,” a pretender, a fake. Ted Nugent took a special dislike. Death threats became a regular part of his life.

At the March for Our Lives one month later, before a crowd of as many as 800,000 in Washington, D.C., Hogg took a deep breath, his voice finding new bass notes when he led the crowd in chants of “No more!” He afterward called for a boycott of Ingraham, forcing an apology from her on Twitter for insulting him (she accused him of whining about not getting into UCLA). After that, he led a coordinated die-in at Publix supermarkets for its contributions to Florida Republican gubernatorial candidate Adam Putnam, who accepted money from the NRA. In May, Hogg and González led the first dance at prom, she in vamp lipstick and he in a red bow tie. In June, they announced their summer plans: Along with other kids from Stoneman Douglas, they would take a bus tour across the country to register young voters. Three legs, 75 cities, two months. The parallels to 1964 and Mississippi were unmistakable.

The sun was setting on Huntington Beach Pier in Orange County, California, last month, where Hogg and his classmates were visiting on week five of their tour. Several hundred people had gathered there for a vigil for the victims of gun violence: little girls wearing French braids and heart-shaped sunglasses, older lefties with weather-beaten faces wearing Obama T-shirts. Hogg was the last person to speak. Wearing a black MARCH FOR OUR LIVES hoodie, he first addressed the problem of police violence against unarmed people of color. Then, with relish, he raised the subject of Dana Rohrabacher, the local congressman in the midst of a surprisingly close race and entangled in Robert Mueller’s Russia investigation. “I tweeted today that I can smell fear, and I think I can smell an indictment, too!” He concluded with the words “Your hope, your vote,” before turning to lead a short march to the beach.

The scene might be taught in future courses on political stagecraft. Hogg positioned himself at the head of the pack, instructed someone to fetch him a megaphone, and led a short chant — “Tell me what democracy looks like!” — striding face-first into the lenses of the backward-scrambling photographers, the sunset reflected in his sunglasses and the wind ruffling his hair. As the procession moved down the boardwalk along Huntington Beach, where a Democrat has not won a House election in 42 years, cyclists and runners and parents pushing strollers stopped and stared at the young man who, having turned 18, looked more than capable of achieving what he told me recently he has decided he now plans to do: run for Congress when he’s 25.

The tour had begun with anti-gun activists on the South Side of Chicago and swept across America, through the cities of the industrial Midwest and Indian reservations and the open-carry state of Texas, up through red California and blue California and then back again, ending finally on the second Sunday in August, in Newtown, Connecticut, where 20 first graders had been killed one morning in 2012 by a man with an AR-15. “We were inspired by what the Freedom Riders did and what the farmers’ movement out in California did,” says Matthew Deitsch, a past graduate of Stoneman Douglas, whose younger siblings survived the shooting and who has taken a leave from college to work with the students. “It was conscious, because these parts of our history really move the dial, really change the way we talk about certain issues.” All this was paid for through the March for Our Lives Action Fund, which was established in the weeks after the shooting, quickly raised more than the roughly $5 million it spent on the march, and continues to support the students’ activities.

The bus was silver and looked impermeable. It carried between 18 and 22 kids at a time, along with a handful of adults. A representative from Precision Strategies, a communications firm founded by members of the 2012 Obama campaign, frequently traveled with them, as well as Michael Skolnik, once the political director for Russell Simmons and co-founder of the Soze Agency, which is “committed to amplifying the authentic narrative of a vibrant global generation.” There was also a therapist on the bus, chosen by the students but insisted upon by their parents, along with a trio of hefty security guards whose job was not just to protect the kids but to constantly assess the level of threat against Hogg in particular.

Hogg, in fact, was frequently not on the bus but traveling separately in a black SUV accompanied by bodyguards. If he were a politician, one of the staffers told me, the intensity of interest in him would merit 24-hour Secret Service surveillance. “We get people armed to the teeth showing up and saying, ‘Where’s David Hogg?’ ” Deitsch told me. An outfit called the Utah Gun Exchange had been following the kids on tour all summer — on what it called a pro–Second Amendment “freedom tour” — sometimes in an armored vehicle that looks like a tank with a machine-gun turret.

The NRA seems to take Hogg’s existence as an affront, having tweeted out his name and whereabouts and inciting its approximately 5 million members by perpetuating the falsehood that the Parkland kids want to roll back the Second Amendment. Hogg’s mother, Rebecca Boldrick, says that in June she received a letter in the mail that read, “Fuck with the NRA, and you’ll be DOA.”

The seniors at Stoneman Douglas all approached this summer differently. Some escaped Florida the minute they graduated; others chose to avoid the celebrity-activist vortex. Mei-Ling Ho-Shing, a student who has criticized the bus tour as not being welcoming enough to the school’s students of color, spoke at the U.N. and, later, attended a spiritual retreat. “I made sure nothing would mess up my week,” she told me. “I did not have my phone, and I did not bring my MSD shirt.” González, both galvanized and emotionally spent, has hired a separate public-relations firm to help her manage the flood of requests for her time.

Hogg has emerged as the leader of a newly invigorated anti-gun-violence movement, the living embodiment of its message and a human front in a new culture war. The refrains he tweets — “The young people will win,” #USAoverNRA — have become battle cries for his young followers, and when big-ticket donors call to contribute to the Parkland fund, what they ask for is face time with Hogg himself. “I think he has no fear,” said Bella Robakowski, a 17-year-old who was waiting to speak with him recently at a block party in L.A., where supporters were eating Ben & Jerry’s while a small group of NRA protesters gathered out front. Robakowski is president of NeverAgain SoCal, one of the countless organizations founded by students in the weeks after the shooting. “Someone needs to get on the news and say, ‘We’re dying.’ ”

A lot of what has catapulted Hogg to this elevated and precarious place is his wonkishness: his dexterity on social media and cable news, his appetite for the nitty-gritty of policy disputes. He is aware of the way his particular talents mesh with how his generation thinks. “It’s like when your old-ass parent is like, ‘I don’t know how to send an iMessage,’ and you’re just like, ‘Give me the fucking phone,’ ” he told a young journalist two weeks after the shooting. At the march, he hung an orange tag stamped “$1.05” off the microphone: It was the price the Parkland students calculated that their senator, Marco Rubio, put on each of their lives, given the donations he’d accepted from the NRA. (At graduation, he attached it to his mortarboard like a tassel.)

Hogg’s Twitter feed is a study in narrative discipline, its relentless focus on the politicians who accept gun-lobby money twinned with exhortations to his nearly 900,000 followers to vote. “People call us snowflakes,” he tweeted earlier this month. “What happens when all the snowflakes vote? That’s called an avalanche.”

“It’s so funny,” says Delaney Tarr, Hogg’s good friend and a founding member of the #NeverAgain crew. “The way David tweets is legitimately the way he is in person. If he has an opinion, he’s not going to silence it for a moment.” Unlike many of his peers, Hogg appears not to care much what people think about him. He’s been bullied before: “I’m easy to pick on because I’m a string bean,” he says. “I’ve had this shit said about me my entire life” — not death threats, but “twig arms and shit like that. I don’t care.” He’s discovered the power of escalation, how calamity can be turned into rage can be turned into provocation. He told one journalist, “The pathetic fuckers that want to keep killing our children, they could have blood from children spattered all over their faces and they wouldn’t take action because they all still see those dollar signs.” At one point, I asked him whether he worries, using that language, about riling up NRA members enough that they threaten his life and his mother’s. “If somebody is stupid enough to try anything on us, that will make the movement even stronger,” he said.

At stops throughout the tour, Hogg meditated in public on the difference between sympathy and empathy. “You can’t have empathy for somebody that’s gone through something you haven’t — because definitionally you can’t,” he told me in an empty seminar room at USC, between a session of a kids’ summer camp and meetings with local legislators. “But you can feel for them and have sympathy for them. And that’s what this country needs to practice more. It’s about realizing that you do come from a different place. I come from a privileged white community in South Florida where the median household income is over $128,000 a year.”

In part, Hogg was trying to address the criticism that he and his movement are siphoning attention away from the underrepresented victims of gun violence. The students at Stoneman Douglas have learned a lot this year about problems in this country that run far deeper than individual sociopaths who can get their hands on an assault rifle. Gun deaths are an epidemiological problem in poor communities, and African-American children are ten times more likely to die from a gunshot than white ones. But he was also reflecting on himself, on his own temperamental impulse to remain disconnected, even haughty sometimes, and the way the events of this year have cracked something inside of him.

Hogg is the son of a Republican father and a Democratic mother. His sister, Lauren, just finished ninth grade; four of her friends were killed in the shooting. Until David was in high school, the Hoggs lived in Torrance, California, where his father, Kevin, worked as an FBI agent at LAX and his mother taught at an elementary school. Kevin always kept a gun in the house — including, when he was on active duty, a rifle called an MP5. He carried his service revolver with him even when he wasn’t working. “I had it on my hip every time I went anywhere,” he says. “I took it to David’s Little League games.” Rebecca says she always hated guns, though she once accompanied Kevin to the shooting range. (In his retirement, Kevin maintains a Glock for personal use.)

Even as a very young child, David was strong-willed. “You could not convince him to do anything he didn’t want to do,” says Rebecca. In #NeverAgain, the memoir David and Lauren recently published together, he reflects on his anti-authoritarian tendencies, recalling how he refused to learn to ride the Spider-Man bike his parents gave him in kindergarten, or to take the sailing or golf lessons they pressed on him. “I would just turn everything into an us-versus-them situation,” he writes.

Also he is dyslexic. He didn’t learn to read until the fourth grade and recalls teachers “telling my parents I would amount to nothing, like I was some kind of broken toy.” He found a way to process their skepticism. “They taught me not to give a shit about what other people think — all that matters is what you think.” Lauren attributes the way he talks today to his early dyslexia. “He gets absorbed in his words because he’s been doubted so much,” she says. “He needs to overcompensate when he’s arguing.”

Hogg frequently uses the word narcissistic in reference to himself. When Kevin was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease and chose to retire and move the family to Florida, with its lower cost of living, David threw a massive fit, refusing at first to go at all — “Screaming up the stairs,” according to Lauren, “ ‘I don’t want to move to Florida! I’m not moving!’ ” — and then capitulating finally but with numerous demands: a new computer, his pick of bedrooms and paint colors. He showed up at Stoneman Douglas in the middle of ninth grade, acting like he already knew everything. He rejected the girls who liked him and looked down on those who didn’t. “He always was an attempter,” says Deitsch, who was running the TV-production club. “He would attempt to be great. He would come into TV production like he was the president, and I’d be like, ‘Sir, I’m in charge here.’ ”

But “midway through my junior year, I kind of had an existential crisis,” Hogg told me. It was familiar high-school stuff having to do with unrequited love and, with college applications looming, an undistinguished academic track record. At 16, Hogg started waking at 3 a.m. to meditate, not with a guru or through an app but following the tenets of Metta meditation. “I sat there in my room very creepily in the dark,” he says. “I would hold on to this rock that I got in California the last time I was out there, when I was hiking with my best friend. You could tell it used to be really rough, but because it was in the ocean so much it was really smooth and soft. It fit perfectly in the palm of my hand, and then I would just hold that and try to focus. It’s really focusing on loving anyone, including those you hate.”

The early-morning regimen of meditation and study seemed to work. He cultivated an identity as a super-dork, fanatical about journalism, always carrying a camera around and suggesting drone shots in the television production club. (He was obsessed with the YouTube filmmaker Casey Neistat and wore sunglasses to emulate him.) In AP Government he always sat in the front row. “He constantly had questions about everything, to the point where other kids were rolling their eyes,” says his teacher Jeff Foster. After class, Hogg worked in the school garden, experimenting with hydroponics in order to develop ways to grow food on Mars.

His grades started to rise and his confidence took on a mellower cast. He became close with González, who was frequently at his house, as well as Tarr and Matt Deitsch’s brother Ryan, both journalism students who are now among the more visible Stoneman Douglas activists. “He was always wearing these little snap-backs,” says Tarr. “He was so awkward and so eager.” This small clique would stake out a lunch table outside in the sun and sit there sweating rather than have to deal with the social stress of the cafeteria. “We’re the misfits,” Hogg told me months ago, before he became famous. “We’re really nihilist. We love making jokes and being self-deprecating. It really lightens the mood.”

Hogg believes this new rootedness prepared him for the events of February 14 — not just enduring the horror of the shooting itself but shouldering the responsibility of speaking for a generation. “It just feels really weird because, like, months ago, nobody knew me at my school, even. I basically knew Emma, Ryan, Delaney, and a few others, but that was it. And now the world knows who we are. It feels like I’m living in a fucking terrible version of The Truman Show.”

Throughout, González has been his guide. “She’s incredibly emotionally intelligent,” he says. The kids in the movement “use her as a translator, essentially, of emotion and sympathy. And she’s helped me more than I’ve ever known about what it means to listen to somebody and actually, just quite frankly, give a shit about them. Because before, even up until junior year, I didn’t really care about people. I only cared about myself.” Tarr has watched the two of them grow closer as they’ve each become spectacularly famous. “They are on a platform that’s leaps and bounds above any of us,” she says. “They know who they were before all this. They understand each other the way nobody can.”

The bus tour was another kind of awakening. “The amount of suffering I’ve seen is beyond belief,” Hogg says. “The amount of inequality is beyond belief.” He has listened every day, multiple times, to stories of personal tragedy. Trans people told him how guns helped to stoke already high suicide rates. Native Americans, too. And parents, of course, talked about losing children for no reason at all. On Father’s Day, Hogg and the other students met Michael Brown Sr., whose son Michael was killed by police in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014. “He told us to close our eyes,” Hogg says, “and imagine the person that we love most, that we hold dearest. And then imagine them being shot and left on hot asphalt for four hours. And not knowing where they were, if that was them, and not being able to see them. I imagined my sister. I imagined Emma. I was really just thinking of, like, pretty much everybody on our team, because we’re all family now.”

Hogg met a 16-year-old girl who was pregnant in a juvenile-detention center — the same jail in which her own mother, at 16, had been pregnant with her. The situation in which that girl found herself, Hogg told me, “that is not evidence of her failing in any way, shape, or form. The system perpetrates that.”

The bus was a retreat for the kids — no reporters, no documentarians. I saw Hogg escape there one afternoon, in the middle of an outdoor event, when the gathering was packed with well-wishers elbowing each other off painted paths into cactus gardens. “I don’t see myself as narcissistic as I used to be,” he told me. “The feeling that I get when I’m on that bus around my friends is the feeling that you get when you take your warm clothes out of the dryer and you put them on your face.”

From the beginning, the tour had two intersecting priorities. The first was to register young people to vote. The second, Matt Deitsch says, was “to make America meet America” — a national consciousness-raising effort around gun violence, introducing kids from different neighborhoods to each other and building coalitions. To put it in 21st-century terms, they were hoping to scale the movement.

Everyone was aware that young people, historically, do not vote. Just 20 percent of people aged 18 to 29 voted in the last midterm election. The kids’ basic idea was to travel to districts where youth voter turnout had been especially low, though they are so focused on Florida they decided to send a second bus to every congressional district in the swing state. They wanted Hogg and González on the national tour, for obvious reasons. They were the headliners, the media draw, and the ones regular people would come out to see. But also, “David has so much hate targeted toward him, we really wanted people to meet him,” says Deitsch. At a rally in Dallas, Hogg and Deitsch hopped a wall to speak with gun-rights protesters after a man in a red STRAIGHT OUTTA MERICA T-shirt approached them to ask if it was true what he heard, that these kids wanted to take away their guns. Hogg assured him that it was not true — his dad was FBI — and that they were for “common-sense gun reform,” like universal background checks. There had been multiple FBI warnings against the shooter at his school, he said. Should that kid really have been able to get a gun? By the end, he and the protester were shaking hands. “They’re not anti-gun! They’re just common-sense whatever,” the man told his friends. “This is what America’s about. Come on, let me shake your hand. Someone take a picture right now.”

Hogg, who had fulfilled all of his Eagle Scout requirements when the shooting occurred and then refused to participate in the initiation because of the Boy Scouts’ affiliation with the NRA, is passionate and earnest about the democratic process in a way that’s far more reminiscent of the Greatest Generation than of his own. He told me, unprompted, about his fantasy of reforming high-school civics education, of making it a requirement for all four years, creating a knowledgeable citizenry that’s invested in the mechanics of government. “People need to realize that people have died for your vote,” Hogg says. “Free college is on the ballot. The draft is on that ballot. Universal health care is on the ballot. Abortion is on the ballot. Supreme Court is on the ballot. Everything that affects your life and, more importantly, affects the people that come after you is on that ballot. Your inaction today will affect you tomorrow.”

Gun violence has become a galvanizing focus for Hogg’s generation, a direct way to engage in a wide range of progressive issues — the environment, racism, inequality. It could, potentially, be the issue that actually gets people to vote, similar to how abortion drove an invigorated cohort of social conservatives to the polls in 1980. Seventy-seven percent of voters ages 18 to 29 say gun control will be an important factor in determining their vote in the midterms, and the share of registered voters in that group is up more than 2 percent nationwide since the Parkland shooting. In certain states — Pennsylvania, New York, Indiana — it’s up much more than that. In Florida, youth voter registration is up 41 percent.

Civic disengagement in poor communities of color is high in the post-Obama years. “Going into 2016, I heard this, and it was painful: ‘My vote doesn’t matter,’ ‘We can’t change things,’ ” says Cornell Belcher, a pollster and founder of the Brilliant Corners research firm. One of the Parkland kids’ explicit goals has been to help turn this around by telling the whole story of gun violence, not just of mass shootings in schools and nightclubs.

At any one time, at least half the kids on the national tour were students who grew up very far from Parkland. Some had made connections with the Parkland kids way back before the march; some were invited on the bus at the last minute. Alex King, a senior from North Lawndale College Prep in Chicago, belonged to Peace Warriors, a support group for students who’d lost a loved one to gun violence. The Parkland action fund had flown him down to meet with the students at González’s house in February, and he had stayed involved in the #NeverAgain activities; at each stop on the bus tour, he told audiences what it was like, at 17, to have attended more funerals than graduations. Bria Smith, a student activist from Milwaukee, was on a panel with them on the first week of the tour. Afterward, one of the students invited her to dinner. Then “Michael Skolnik pulled me aside and asked me for my perspective on the tour. I was so shook to my core when they asked me to come.” The next morning, her mother drove her to meet the kids at their hotel, and together they hit the road.

Smith comes from a neighborhood where gun violence is so ordinary that as a child she believed it was normal. “In my community, it’s easier to get a gun than it is to find a parking spot,” she says. As a teenager, she joined as many activist and organizing groups as she could. The media frenzy around the Parkland shooting was difficult to watch. “So many people giving media coverage to a couple students, I felt really salty,” she says. “We’re not given millions of dollars in donations.” And when she met Hogg for the first time, “I thought he was another white boy.” At her school, Smith says, “I hear white boys speak about politics all the time.” And then he did something she thought was extraordinary. “He asked me a question that no other person has asked me. He asked, ‘What do you need? We can get it for you.’ And I thought, Whoa. Maybe I do need to speak up about that. Maybe I do need to ask for favors.”

The Parkland kids did their best to cede the spotlight and neutralize some of the structural inequalities they were spending their days talking about. It didn’t always work, though. When the tour came through New York, González and Matt Deitsch were invited on the Daily Show; in Newtown, while the official program of speeches by Connecticut activists and Newtown students took place in a humid tent, the real action was behind the tent, where Senators Richard Blumenthal and Chris Murphy and three gubernatorial candidates all scrambled for face time with González and Hogg.

At a session of a Freedom Schools summer camp at USC — while younger kids sang and chanted and danced around him — Hogg receded completely, slinking down in his chair and pulling his cap over his eyes. When participants were asked to stand and fill in the sentence “What sparks my interest in justice,” Hogg said what was clearly on his mind: “What sparks my interest in justice is how people aren’t treated equally by the press.”

Jammal Lemy, a Stoneman Douglas graduate who returned to Parkland after the shooting to help with the organizing effort, wishes Hogg would relax. “He overcompensates for his white guilt,” Lemy says. “He wants to fix everything. He needs to be more of a hand of support rather than a crutch.” Hogg told me that if he’d learned anything on tour, it’s how to listen. “I’m not here to speak for anyone,” he told the website Complex.

At an event at the California African American Museum in L.A., Hogg did not speak at all. He sat backstage with his phone beside a long table littered with half-eaten Chick-fil-A, while in the auditorium a panel of Parkland students and local activists assembled by a Black Lives Matter group discussed urban gun violence. After the panel, I watched González, who is tiny, get swarmed by an admiring throng and then, upon hearing that two women in wheelchairs could not approach the stage, vault over her fans to hug them. When Hogg emerged from backstage to shake hands and chat, he stood slightly apart, dutifully posing for selfies, giving each person in turn a small, mechanical smile. Later, out in the parking lot by the bus, the kids were fooling with Hula-Hoops. Ryan Deitsch demonstrated expert-level skills. González was pretty good. Hogg held his Hula-Hoop away from his body, game but hesitant, not quite sure he was up for the gyrating it required.

And then suddenly he was on fire again. Maybe he got a good night’s sleep. Maybe it was his visit to his grandparents nearby. All the kids had accompanied him there on the Saturday after the Freedom Schools session, filming his grandparents’ 30-year-old pet tortoise, Toby, as he munched on a humongous leaf and then tweeting the video to his followers, comparing the wrinkly reptile to Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell. When he walked into the COR AME Church in Orange County that morning, he was still laughing at the video, passing it around and counting the thousands of retweets.

More than a thousand people had arrived at the church to hear the panel on gun violence. It was standing room only, security everywhere, a sign-language interpreter, and giant video screens magnifying the stage: five local activists on the left and the Parkland kids on the right. Hogg was seated at the far end of the panel, his long legs sticking out from beneath the tablecloth. Every time he offered an insight or a sound bite, remarks he must have made hundreds of times by now, the audience cheered as if he were speaking truths they were desperate to hear. “Honestly, Wounded Knee was the first mass shooting.” “In the same way we all have a right to bear arms, we all have a right to live.” “If you are shooting someone from 1,600 feet away, you are not defending yourself. You are hunting.”

Hogg is adjusting to sudden fame in all the ways you might expect — he wears it uncomfortably sometimes, then other times it’s as if he has practiced for it his whole life. (“He’s like, ‘I’m not a celebrity,’ ” his mother told me, “and I’m like, ‘Shut up. You’re a fucking rock star.’ ”) After the panel, the line to see him, hug him, and take photos with him snaked almost to the back of the room, and he was clearly enjoying himself. I saw, in every place we went, teenage girls hovering just outside his circle. “I think he’s really cool, obviously,” a 15-year-old named Sami Shanman told me one night, as she waited to interview him for a teen-news website. “For me, it’s the way he speaks. He’s the one I’ve seen the most hate on. But he’s also one of the strongest in the movement. He is so strong and not going to give up.”

At one point this summer, I asked him if he was ever tempted by all the attention from girls his age. “No,” he answered. “They think they know me, but they only know the me that I choose to put out there. Emma and Delaney, and the people in our group — they know me. I may be a teenage boy and a walking hormone, but I just care about everybody.” Later that evening in Orange County, at a bonfire on the beach, Hogg was talking to half a dozen girls who were looking for advice on how to organize anti-gun movements at their schools. He talked about the way women get shafted at work and in culture. “Promise me you won’t take anybody’s shit,” he said. It was as teen-earnest as a John Hughes movie. Then he looked around at the blackness, the beach, the waves. “Beaches are a place for a mass shooting,” he said. “I hate to bring that up.”

Hogg is working on a seven-year plan. Now that the bus tour is over, he and his friends in the March for Our Lives organization plan to spend the next several months meeting more activists and canvasing in advance of the midterm elections. And if he could design his future without any obstacles, he would go to college in the fall of 2019, “read a shitload of books,” then take some time off in 2020 to work on a presidential campaign.

(Certain candidates have already approached him, he told me.) Then, after college, he would prepare for his congressional run. “I think I’ve come to that conclusion,” he says. “I want to be at least part of the change in Congress.”

In the past five months, Hogg has developed political opinions on just about everything. He is against charter schools and for universal health care. He is obsessed with Mueller’s investigation and especially the indictment of Maria Butina, the alleged Russian spy who infiltrated the NRA. He believes that Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez is “a future president of the United States.” He is interested in the idea of placing age limits on politicians. “The reason Republicans are successful right now is because they’re empowering young people,” he told me, pointing out that Paul Ryan was 45 when he became Speaker of the House. “Older Democrats just won’t move the fuck off the plate and let us take control. Nancy Pelosi is old.” I am old enough to be Hogg’s mother, and pushed back on the idea that age equals ineptitude. Later, he posted a survey on Twitter. “I had an interesting conversation today when the question of congressional age limits came up. Do you think there should be an age limit on congressmen, congresswomen, and congressthem?” Of more than 33,000 votes, 59 percent said yes.

His antenna for adult hypocrisy has made it especially difficult to find a comfortable vision of a future self — he sees so few real-life examples of the kind of politician he aspires to be. Bernie Sanders: “A great guy, terrible on guns.” Obama: “He increased drone warfare and killed a lot of civilians.” Hogg’s mother says that from birth her son has been an old soul and preternaturally mature. But sometimes he thinks and speaks exactly like a teenager. “Honestly, they all kind of suck,” he said.

More immediately, Hogg needs to figure out college. He has declined an offer of admission at UC Irvine, where he might have otherwise gone, but applying to schools again this fall isn’t very appealing — he knows he tests poorly, and he doesn’t like to write. Then there’s the problem of money. Kevin Hogg has always been famously cheap, and now that his health is deteriorating, his son is preoccupied with how he’ll pay for the stuff he needs: college, gas, food. “Wherever I go, I want to go for free, because I don’t want to put that over my parents or myself.” The students on the tour had received a stipend from the action fund — Hogg earned about $6,000 — though they received it with ambivalence, some referring to the payments as “blood money.”

Of course, Hogg is now the kind of applicant many colleges would be happy to consider. Hogg’s mother told me that even Harvard is a possibility. The family was in Boston in the spring, at a gala dinner — “They shut down Fenway Park, and I was like, ‘Oh, wow, these people know how to party’ ” — and Harvard professors kept coming up to their table and introducing themselves. David went on a private tour, and Rebecca says that alumni told her, “There is the potential that your son will be the leader of this country, and we want to make sure he goes to Harvard.” Rebecca was out of her mind with pride. But “we could never afford Harvard. Never. It wasn’t on our radar. I looked it up and saw how much it cost and said, ‘There is no way.’ With any luck at all, he can get into Harvard and they can help us financially.” (Harvard declined to comment on potential candidates.)

Backstage at the AME church, while the kids were still laughing from their visit with the tortoise, Hogg approached me. It was clear that all of the decisions he faced were piling up and making him crazy. He is being bombarded with offers and opportunities from everywhere. One of the California colleges that had rejected him just invited him to a paid speaking engagement. The tour was moving to Oakland next, where Hogg was planning to meet briefly with a Silicon Valley philanthropist who wants to pick his brain about strategies for youth engagement. “I’ve been offered jobs that are six or seven figures” — at media companies, at nonprofits. Recently, he met Michael Bloomberg and asked him how he schedules his life. “He was like, ‘I have a scheduler.’ ”

Hogg has always been earnest, Lauren says, but in recent months he has grown even more so. “He’s very critical of everything and he’s super-serious, and that has become his whole life,” she says. At an age when all decisions feel consequential and all outcomes dramatic, Hogg’s reality corroborates that perception. He is hyperaware of the terribleness of his circumstance, that his own future has opened up through the unimaginable murder of 17 people and is built, in some ways, on the inevitable deaths of others. On his right wrist he wears a collection of brightly colored bands stamped with the names of the Stoneman Douglas dead, and he tries to keep them constantly in mind. “A kid is going to die today on the South Side of Chicago,” he told me a few minutes before it was time to speak. “And I hate to accept that reality.”

We finished talking, and he left to take the stage, where I watched him heed the advice he regularly gives to teenage fans who ask what they can do if they’re not old enough to vote. “The most important thing about being young is your face,” he tells them. “Get in people’s faces.”

*This article appears in the August 20, 2018, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!