One of the most overrated and misunderstood political phenomena of the modern era is 1994’s Contract With America, a ten-point set of “promises,” often not very specific, embraced by House Republican candidates, who went on to win big in the midterms and regain control of the House.

It was adopted so late (September 27) in the midterm cycle that it could not be said to have represented the bulk of GOP messaging in 1994. Polls showed most voters had never heard of it. As James Fallows observed at the time, it dodged many issues on which Republicans didn’t entirely agree. And to the limited extent that it mattered politically, it wasn’t so much the agenda it advanced but the idea of a “contract,” a set of pledges the party promised to keep if it won, that was the big deal. It became legendary partly because one of its authors, soon-to-be-Speaker Newt Gingrich, flogged it incessantly, and also because the 1994 GOP House takeover — the first in 40 years — seemed like an earth-shaking development at the time instead of being the culmination of all sorts of trends (e.g., ideological polarization, the consummation of the white southern flight to the GOP, a record number of Democratic retirements) that had finally matured. There is very little doubt Republicans would have won the House without the Contract.

But here it is again, along with 2006’s Six for ‘06, as a key piece of evidence in a New York Times indictment of the Democratic Party for failing to adopt a comprehensive and detailed national agenda in its drive to regain the House:

For at least the past 20 years, whenever a party has won control of the House, it has done so with some kind of unifying message or pitch. In 1994, Republicans ran and won on their “Contract With America,” a 10-point legislative plan. In 2006, Democrats flipped the House with a legislative platform they called “Six for ’06.”

But this year, says the Times, the Democrats, riven by ideological divisions and unable to tell voters who they are, are fleeing from this essential tool:

House Democrats, looking to wrest control of the chamber from Republicans in November, are discarding the lessons of successful midterms past and pressing only a bare-bones national agenda, leaving it to candidates to tailor their own messages to their districts.

It is a risky strategy, essentially putting off answering one of the most immediate questions facing the Democratic Party after its losses in 2016: What does it stand for? The approach could also raise questions among voters about how Democrats would govern.

There are a lot of problems with this argument. The most fundamental is the implicit claim that voters have enormous curiosity about “how Democrats would govern” in a midterm election driven, as they always are, by attitudes toward the president of the United States. The particular POTUS in office right now has dominated news coverage and political discourse to an extent prior imperial presidents could not have imagined . Democrats could publish 100-page agenda books and together croak out poll-tested message slogans like frogs after a summer storm — but it’s not going to override the basic fact that Democrats are the party that’s not the party of Donald J. Trump.

Besides, Democrats have articulated some common principles and policy goals, as the Times acknowledges while mocking them as “only a bare-bones national agenda.” As noted above, the Contract With America had its soft spots and evasions, too. And parties have always left “it to candidates to tailor their own messages to their districts.”

I wrote about national politics in 2006, and I honestly don’t remember a thing about the “Six for ‘06” platform of that year. I do remember an electorate that was weary with the Iraq War and disgusted by the Bush administration’s shabby domestic governance (viz. Hurricane Katrina) turning against the president’s party, as it so often does. I also don’t recall any tightly constructed GOP national programmatic agenda in 2010, when Republicans picked up 63 House seats and regained control of the chamber, or in 2014 when they made additional gains (an election about which I wrote a whole book).

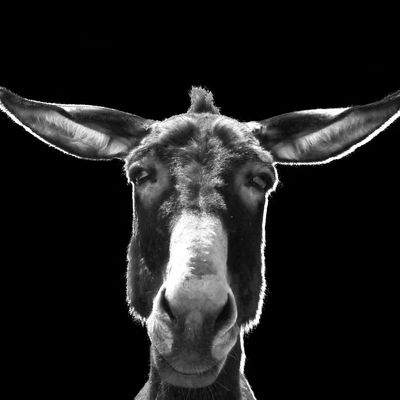

What seems to be driving this argument that something’s terribly wrong with the Democratic midterm campaign is a conviction that the Donkey Party is so paralyzed by ideological divisions that it can’t do the obvious thing by writing up a campaign platform or a five-year plan.

[A]s Tuesday night’s election results made clear, the primary season drawing to a close has made the search for a unifying message that much more difficult, elevating self-described democratic socialists like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in New York and Rashida Tlaib in Michigan to argue policy with a Trump-voting populist like Richard Ojeda in West Virginia and a centrist like Conor Lamb in Pennsylvania.

But here’s the thing: they aren’t arguing with each other; they are running their own campaigns. And anyone who thinks policy divisions in the Democratic Party are sharper than they were 10 or 20 or 30 years ago has a very limited memory.

When it’s not blasting Democrats for failing to have lockstep unity, the Times piece offers fine anecdotal evidence of Democratic candidates around the county who are indeed “tailoring their own messages to their districts.” There is no absence of enthusiasm in the party base, and at this point it looks like Democrats are poised to make gains in districts as dissimilar as Conor Lamb’s 18th Congressional District in Pennsylvania and Latino-heavy suburban districts in Orange County, California.

Yes, if Democrats win the House they will need to get their act together more uniformly and systematically. And in the 2020 cycle they will nominate a presidential candidate who will indeed define the party, just as Trump has come to define his. Right now they need money and smart tactics and good strategies for getting out their vote. What they don’t need is their own Contract With America.