Chances are that you’ve never heard of General Magic, but in Silicon Valley the company is the stuff of legend. Magic spun out of Apple in 1990 with much of the original Mac team on board and a bold new product idea: a handheld gadget that they called a “personal communicator.” Plugged into a telephone jack, it could handle e-mail, dial phone numbers, and even send SMS- like instant messages—complete with emoji and stickers. It had an app store stocked with downloadable games, music, and programs that could do things like check stock prices and track your expenses. It could take photos with an (optional) camera attachment. There was even a prototype with a touch screen that could make cellular calls and wirelessly surf the then- embryonic web. In other words, General Magic pulled the technological equivalent of a working iPhone out of its proverbial hat—a decade before Apple started working on the real thing. Shortly thereafter, General Magic itself vanished.

Andy Hertzfeld: The Macintosh had a great launch; it was really successful at first. Steve laid down a challenge at the introduction, which was to sell first thousand machines in the first hundred days, and it exceeded that. But then starting in the fall, sales started dropping off.

Steve Wozniak: It just didn’t have any software at first.

Fred Davis: MacPaint and MacWrite were like demo programs. They weren’t real tools that you could use to do stuff.

Steve Wozniak: The Macintosh wasn’t a computer—it was a program to make things move in front of Steve’s eyes, the way a real computer would move them, but it didn’t have the underpinnings of a general operating system that allocates resources and keeps track of them and things like that. It didn’t have the elements of a full computer. It had just enough to make it look like a computer so he could sell it, but it didn’t sell well.

Andy Hertzfeld: By December of 1984 the forecast was to sell eighty thousand Macs, and in fact they sold like eight thousand. So something had to be done. If the Mac wasn’t going to catch on, Apple didn’t have a future. So what to do about it?

John Sculley: In 1985 Steve introduced the Macintosh Office, which was a laser printer—the LaserWriter with PostScript fonts from Adobe—and a Macintosh. One problem: The product just didn’t work. It wasn’t until at least a year later that the microprocessors were powerful enough that you could actually do the kind of things we were actually promoting back in 1985. So people weren’t buying it.

Steve got depressed. And then he turned on me.

Andy Hertzfeld: It got to the point where Steve was openly sabotaging Sculley. Something had to be done. Sculley and the board didn’t fire him, but they removed his responsibility from running the Mac. And so he had to leave.

Ralph Guggenheim: Steve left in 1985. There was a rumor that he was starting a new company, NeXT.

The NeXT machine was Steve’s effort to build his vision of a desktop workstation with lots of computing power and a CD-ROM. It was his attempt to show what he could have done at Apple.

Steve Perlman: It was big, it was black-and-white, it was clunky.

Andy Hertzfeld: NeXT was a revenge plot. That’s the reason I didn’t work at NeXT. Steve denied it and we’d argue till he was blue in the face. But it was true: The purpose of NeXT was to eclipse Apple. And I loved the Mac. I didn’t want to work against the Mac. But Steve wanted the Mac to fail, and so he started NeXT.

Meanwhile, back at Apple:

Larry Tesler: Steve was gone. Where are the new ideas going to come from now that we got rid of Steve? We’re going to run out of Xerox’s ideas. Where are we going to get ideas from? The management wanted new ideas. And so they decided they needed what they were calling the Advanced Technology Group. It was really an R&D group, a lab.

Steve Perlman: We were building a color Macintosh.

Steve Wozniak: The Mac wasn’t ever really selling until we introduced the Macintosh II in ’87.

It had color.

Larry Tesler: One of the things that grew out of it was the Apple Fellows Program. The first three Apple Fellows were Steve Wozniak, Bill Atkinson, and Rich Page. The initial definition of a fellow was someone who had made a big impact on the industry. Al Alcorn was recruited—he had done Pong. And they also wanted to recruit Alan Kay. So we brought them both in.

Alan Kay: Steve never forgot where his ideas came from.

Andy Hertzfeld: Alan Kay was my hero. I was like Damn! But it was still time for me to quit.

Larry Tesler: And then as the program expanded and it even included a person who was not an engineer—Kristina Hooper Woolsey.

Kristina Woolsey: I came in ‘85 when the HyperCard stuff started. Bill Atkinson spontaneously decided to do the product. He and a small team just popped this thing out.

Al Alcorn: HyperCard was developed by Bill and two or three guys in Advanced Technology and—it wasn’t supposed to be released. Products are supposed to be released by Product Development, not by Advanced Technology, understand? But Gassée, who succeeded Jobs as head of Macintosh development, wasn’t going to have it. So Bill and his team just conspired. And while Jean-Louis Gassée did his French thing and went off for a two-week summer vacation on the beach in the south of France, Bill just released it. And when Gassée got back he was furious, but he couldn’t stop it because HyperCard was really well received. It got great press. There are a lot of stories like that.

Andy Hertzfeld: But the beginning of General Magic is really Marc Porat. He’s a very clever nontechnical person—an impresario businessman who in the thesis he did at Stanford came up with the first use of the term “information economy.” Marc was a college friend of Larry Tesler’s. So that was his connection to Apple. And he was hired on in the fall of 1988 to work in the Advanced Technology Group at Apple to try to help figure out what’s the next thing beyond personal computers.

Megan Smith: Marc was very tied into Nicholas Negroponte and is part of that whole MIT Media Lab conversation.

Andy Hertzfeld: Marc started by interviewing everyone at Apple trying to come up with a consensus—what’s in the wind. Eventually he decided the next thing beyond the personal computer combined two things. One is communication. The other thing is instead of being on the desk it was in your pocket.

Megan Smith: And Marc came up with this idea that he called a Personal Intelligent Communicator—a smartphone, basically. The whole idea was there.

Marc Porat: Remember something called the Sharp Wizard? It was a screen with some chiclet keys: one of those silly little organizer things, but useful. I took that and a Motorola analog cell phone and I duct-taped them together. That was the concept: “Imagine this screen was beautiful, imagine the applications were amazing, imagine that it was linked wirelessly with you everywhere.” And that little concept went around, and then we reduced it to something that was smaller and more beautiful.

Andy Hertzfeld: And the smartest thing he ever did to make his vision real was make little models out of plaster.

Steve Perlman: He was showing what looked like a little wallet—a block of plastic wrapped in leather.

Marc Porat: Everything was going to become very small and in your hand, and intimate and jewelry-like. You’d wear it all the time, and if there was a fire in your house you’d think, Family goes first, and then I grab my Pocket Crystal.

Megan Smith: Pocket Crystal—that was his nickname for it.

Andy Hertzfeld: The first thing I said when I saw his models was, “Well, they’re not realistic.” And he said, “I know—but they will be.”

Michael Stern: Marc Porat was an incredible visionary. His Pocket Crystal project at Apple was really a previsioning of everything that we now take for granted.

Marc Porat: I wrote a book on it, all the things that this thing is supposed to do and why this computing-communication object would change the world.

Michael Stern: Devices in your pocket, social networking, social media, a notion of an electronic community, anytime-anywhere communication, handheld devices that could enable you to do just about anything from shopping to research to talking to your mother. It’s all there, in that book he wrote. He was at Apple to help springboard the project and get it funded.

Al Alcorn: So Marc was pushing this thing, and he infected Bill Atkinson and some of the other guys with this idea.

Andy Hertzfeld: Marc met with Bill Atkinson, who had just finished HyperCard and was kind of looking around for what to do next. And he got Bill really excited about it. So one day right after my friend Burrell Smith went insane and I was dealing with that emotionally shattering experience and all of the fallout there, I get a phone call from Bill, incredibly excited, “You’ve got to see this new thing at Apple! It’s the next thing!” And my first thought was, Oh my God, Bill went insane too!? But he didn’t. And I called Bill and he said, “You’ve got to meet with this guy Marc.” And so Marc called me up.

And I said, “Yeah, this is pretty interesting but I don’t want to work at Apple again.” And Marc said, “I understand you don’t want to work there. Why don’t we just pay you to be a consultant, and you know, just get started?”

Marc Porat: Bill loved it. Andy saw it, was impressed that Bill was there. Bill was impressed that Andy was there. They immediately started seeing how to do it, and they signed up.

Andy Hertzfeld: Bill created a prototype user interface in HyperCard. I wrote a server that allowed you to send little electronic graphical messages.

Michael Stern: There were these beautiful little “tele-cards” with animations and handwritten notations and sound embedded in them.

Andy Hertzfeld: All kinds of whimsical wacky animations—like we had a walking lemon. As well as these little graphical decorations also had meanings associated with them. Some of them you could even interact with, like one that was lips with a speech bubble. When you tapped on it a microphone appeared and you could talk into it and it would send your voice as part of the tele-card.

Michael Stern: These beautiful little things you could exchange with each other. That was Bill’s thing.

Andy Hertzfeld: We had what are now called stickers, which is part of instant messaging. You know how you could use little stickers in your messages? We had that working twenty-some years before the iPhone, in a better way than most people have it now.

Steve Jarrett: You’ve got to remember, this was before even digital cellular existed.

Marc Porat: Many of us had analog cell phones, which were bricks, and some of us carried batteries in a little, tiny briefcase to go with the brick.

Steve Jarrett: People were just using mobile phones to talk. So, it’s very, very early.

Marc Porat: The theory and the strategy, right from the beginning, was to create a global standard. Apple and Microsoft would have the personal computer, IBM and Digital would have the bigger hardware, and we would do everything else. We would do telephones, we would do television set-top boxes, we would do kiosks, we would do absolutely everything else that had an operating system.

Al Alcorn: But it clearly wasn’t going to get supported by management at Apple. It wasn’t going to happen.

Marc Porat: It would need a lot of communication networking, including wireless, and it would need something that did not exist, which was a network to run on, which Apple did not have.

Andy Hertzfeld: One company can make a computer, but it couldn’t make a communicator all by itself, because it wouldn’t be able to establish the communication standards. So it couldn’t be an Apple product.

Marc Porat: But it was also clear that politically, it was going to be okay to spin this thing out.

John Giannandrea: I think a big part of spinning General Magic out of Apple was this idea that it was too big even for Apple, right? Apple couldn’t deal with this thing.

Marc Porat: So there were two projects established: General Magic on the outside, and Newton on the inside.

Andy Hertzfeld: The Newton project was an 8-by-11 tablet that was supposed to cost $5,000.

Marc Porat: The Newton was a hedge in a big strategy that we had described to Sculley.

Andy Hertzfeld: Basically Marc convinced John Sculley to not only let us spin out from Apple but also to help us convince Sony and Motorola that they should join Apple in trying to create this new standard. We called it “the Alliance.”

Marc Porat: Apple, Motorola, Sony: So now we had the three board members as licensees, who were the core of the founding partners.

Michael Stern: This is before the web; this is 1990–1991. And so after we’d already formed a company and spun out of Apple …

Andy Hertzfeld: We decided to bring AT&T into the fold. AT&T became the fourth investor in General Magic on par with Sony, Motorola, and Apple. And that kind of worked, I was surprised. We were off and running.

John Giannandrea: It was a ridiculously ambitious company.

Marc Porat: People of enormous quality began to come over and see what this crazy team in downtown Palo Alto was doing—and joined.

Andy Hertzfeld: We had a lot of the original Mac people.

Steve Perlman: It was a great group of people. To have a chance to work side by side with Andy and Bill? Come on! They’re the real deal. These guys are just geniuses. I didn’t care if they called it General Pickle. I was going to work side by side with Andy Hertzfeld and Bill Atkinson; what else could anyone ever dream for, right? I think I was employee number thirteen.

Michael Stern: Andy and Bill were the gods of the universe, and then these kids came to work for them. Andy in particular was the mentor for and helped train a cohort of brilliant kids. Many of whom had their first job at Magic, like Tony Fadell.

Tony hung around and would just talk to people until we finally hired him.

Tony Fadell: I had my own start-up in Michigan doing educational software and getting frustrated being a big fish in a little pond. There was no internet then, so I would religiously read MacWEEK and Macworld, and there was always the last page of each of those rags which were like the murmurs, the rumors, the goings-on, and this company called General Magic kept popping up in it. I was like, Whatever that is, I have got to learn more about it.

Marc Porat: General Magic had all the buzz. All the buzz. It was where the pixie dust was.

It was where you wanted to work if you were cool and smart.

Tony Fadell: I am looking all over for General Magic, and I find out that their office is in Mountain View in this high-rise, and so I show up about eight thirty in the morning with a tie and a jacket on, with my résumé in hand, and walk in the door. There was no one around. Or at least I did not think so. So I walked down the hall, and I saw a couple people who looked like they had been there all night. I was like, “Hey! I wanted to bring my résumé by, wanted to see if you guys were hiring?” They looked up at me with these bloodshot eyes, like, “Leave us alone, kid.”

Michael Stern: But Tony just keeps pestering people until they hire him.

Tony Fadell: I was humbled in the first ten minutes of being there, I was like, Oh my God, this is not like Michigan, these are the smartest people ever, I have got to be working here. Whereas Apple was still making computers, these people were making the next form of a Mac! It was the iPhone, fourteen years too soon. It had a touch screen, it had an LCD, it was not pocketable but it was portable—the size of a book. It had e-mail. It had downloadable apps. It had shopping. It had animations and graphics and games. It had telecommunications—a phone, a built-in modem. I was like, I want to go with them, where they are making this stuff from scratch. I can be part of it.

Marc Porat: He just walked in the door and impressed Bill and Andy and got his first gig to do stuff. General Magic was Broadway, and Andy and Bill gave this kid from the Midwest somewhere a break.

Tony Fadell: Ultimately, they gave me the job, and I was the lowest guy on the totem pole. I came in and I was working with my heroes.

Michael Stern: We had a building right on the Mountain View–Palo Alto border. That building had been empty for ten years, and it had a pack of feral dogs living in the basement. So we were the first tenant. We had the top floor. It was a jungle. I mean they had built like a model railroad that ran up the top of the building.

Tony Fadell: That was not a train set, that was a remote-controlled car track, but I had a Lego train set in my cube and put that up, and a bunch of other toys in my cube.

Michael Stern: We had Bowser, the pet rabbit which lived there and would shit everywhere.

Steve Perlman: Bowser was never trained to use kitty litter, so he would leave little gifts around the office. I typically walk around barefooted, and I would collect these little gifts between my toes. But Bowser was so cute and adorable—we all loved him.

Michael Stern: People brought their dogs and the parrot few around and the trains rattled around and everybody lived there kind of 24/7.

John Giannandrea: Zarko Draganic famously slept under his desk for months at a time. Zarko shared a cube with Andy Rubin.

Megan Smith: You’d say “Hey Zarko, let’s meet at three o’clock.” And then he would say, “A.M. or P.M.?”

Michael Stern: The kids, they just worked nonstop. They’d work in bouts.

Megan Smith: That’s what the kids in Silicon Valley do in their twenties. We work like crazy and have an amazing time. Maybe some other folks are busy partying or doing whatever they’re doing, but the Silicon Valley kids are inventing together and that’s the community.

John Giannandrea: It was fun times. The place was kind of crazy, too.

Marc Porat: The culture and the environment was Apple done even more fun. We had meals, we had spontaneous music things going on. We had Bowser running around. We had gunfights—Tony was the chief antagonist or protagonist with water weapons. He would start battles with water guns and pistols, and it was really fun.

Steve Perlman: So much fun! But too much fun.

Tony Fadell: Remember Gak, or Slime, the green slime? We would leave it on stuff, and we had all kinds of practical jokes on each other.

Amy Lindburg: I hid a hot dog in Tony’s computer, and he retaliated by putting a pickle inside my computer and it shorted out a whole bunch of stuff. There was just always some little joke going on. It was just, we spent all of our time there. Every night was late night.

Tony Fadell: We were known to work really late. Eleven or twelve, even four in the morning. It just depended. So this was about ten or eleven o’clock at night, and we were all getting punchy. We were like, “Let’s get out the Gak and the slingshot!”

Steve Jarrett: Somebody, late one night, had built a funnelator. It’s like a slingshot, it was surgical tubing that could shoot anything. And so, Tony and a bunch of other guys decided that they would put a bunch of this gel inside of the funnelator…

Steve Perlman: People were having a meeting in an upper-story conference room and we thought it would be really funny if we went and shot Gak so it splattered on the outside window. We’d watch it drool down.

Tony Fadell: So who was it? I think Perlman and Andy were holding it on either end, and because earlier in the day we had lined it up, I was like, I am really going to pull this thing back.

Steve Jarrett: Tony’s really strong.

Tony Fadell: Everyone is cheering me on: “Go, go, Tony!” So I am pulling it back and pulling it back, and they are like, “Go!” and I am like laying down on this thing, and the thing goes “whoosh” and then “pop!”

John Giannandrea: The green slime went straight at the window and then the window just shattered—fell out of the building. And we were like, “Ooops.”

Tony Fadell: I just looked, and my whole life flashed before my eyes. I am like, Oh fuck, I am going to get fired, what am I going to do!? And we have an all-hands meeting the next morning. So I go, and I sneak in the back just as it was starting, and then of course everyone knows what I did, all of a sudden everyone is just like, “There’s Tony!” and they just start clapping, and they are laughing and cheering, and I am like, I broke a six- thousand dollar window, and everyone is laughing and cheering?

Marc Porat: I said all was forgiven. Do not even worry about it. There were no rules about having fun.

There were other sorts of breakthroughs, as well—technological ones.

Steve Jarrett: So Tony and I were two of the youngest employees and visibly so. At the time, we were probably—I don’t know, I think we were maybe twenty-three and twenty-four. We have a trip to Japan which, because I’m the Japanese business development guy, I helped organize. We go to see all our partners there and we’re going to describe the design of the new hardware—the new chips and the entire layout of the next generation of the hardware that we’re creating.

Tony Fadell: Japan was it for electronics in the early nineties. Even Apple could not make small stuff back then. And Mitsubishi Electric was a partner of General Magic’s. Our job was to work with them on building new chips for our devices.

So we presented the architecture for the next generation General Magic device—showing it off.

Steve Jarrett: We go into this meeting and Tony gets up and on the overhead projector, puts down a slide, and he starts to walk through the diagram.

Tony Fadell: I am going through the block diagram, explaining it, and they were all, “Oh, yes, that is great, wonderful.”

Steve Jarrett: And so, Tony gets to the part where he’s describing the modem. He says, “Well, then here’s where you can connect the telephone cable.”

Tony Fadell: And they go, “But Tony-san, where is the modem?”

Michael Stern: In the block diagram there was no modem chip.

Tony Fadell: I said, “In software.”

Steve Jarrett: They all look at each other and one of them says, “Honto desu ka?” which is “Can it be true?” The other guy just kind of shrugs his shoulders. Then they immediately just start yelling at each other in Japanese. One of them jumps up and grabs the telephone that’s in the room and yells down the phone. They ask us to stop and wait.

Tony Fadell: Just then the boss, Nagasawa-san, comes into the room and sees this activity. And as this happens, the loudspeaker goes, “Beep beep beep,” and we are like, “What is that?” And somebody says, “Oh, there is a typhoon warning. We all need to leave before noon, because we need to get home because the typhoon is coming.” I go, “Really?” and they go, “Yeah, but we are going to keep working.”

Steve Jarrett: Five minutes later, guys in all these multicolor factory jumpsuits show up and fll the room. And then they say, “Tony, again, please. Please describe your architecture.” So Tony gets to the part and he says, “Well, this is where there’s no modem because we’ve done it entirely in software.” The one guy grabs his head in his hand and just hits his head on the table. I said, “Is everything okay?” The guy who organized the meeting says, “You have just obsoleted Kato-san’s division.”

Tony Fadell: So while the whole of Mitsubishi Electric is being evacuated, the CEO and that team and us stay there the whole afternoon and we sat in this room, and I think even at some point the power went out and we just kept talking. How do you do this modem in software? How do you do this device? They were blown away by the system-on-a-chip low-voltage all-in-one design and the software modem. The CEO had never seen anything like it.

Michael Stern: They were selling hundreds of millions of dollars in modem chips. And we made it so you don’t need a chip anymore. So that was the kind of stuff that Magic accomplished. Again, Magic’s DNA was Apple. We were Apple all the way. I mean here is a little start-up with limited working capital, and we are designing our own chips instead of going and buying them? Absolutely insane.

Amy Lindburg: The OS, the hardware, the soft-modem: All those achievements were amazing at the time. It was like the Apollo Project.

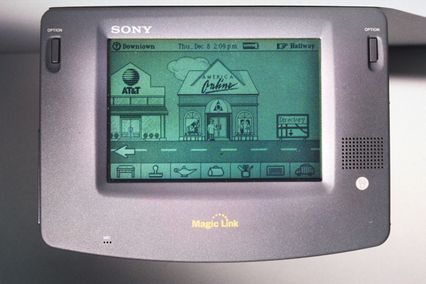

Steve Jarrett: The user interface was really visionary, too. It was groundbreaking. It was based on the real world.

Tony Fadell: Each thing was a mock-up of the real world, and you would interact with those things like you would interact with the real world.

Steve Jarrett: You started at a picture of a desk and you could drag things around on the desk and you tap on things to open them.

Tony Fadell: It was skeuomorphic—like file cabinets to put your things in, a desk to write on…

Steve Jarrett: And then you could leave the desk and go into the hallway. And in the hallway there’d be doors.

Michael Stern: You’d click and behind the doors were various rooms—like the game room, the media room, the library. In the library there would be all your books, all of your electronic books. And we’d written some manuals so there would be something to populate the library. And in the game room we had the first networked games. You could play online with opponents. No one had ever done it before! Again, this was something Tony just kind of whipped out in a day.

Tony Fadell: And you would go out the door and you could go down the street and go to a shop which would be a virtual shop.

Michael Stern: This is where the third-party developer community was connected. Because remember it was all about being a platform, not a closed system, so that third-party developers could develop applications. Productivity applications, games, you name it: They had them. We actually had wonderful games in the game room.

Megan Smith: Pierre Omidyar was running all the developer services stuff.

Steve Jarrett: Pierre was doing really early, really interesting work of thinking up online services that would work on these mobile devices that we were creating. He created a turn-based chess game that was easily the most popular game on our platform.

Tony Fadell: It was pretty neat, you know?

Michael Stern: So we were demonstrating all this stuff. Meanwhile Marc is talking up the vision of the global community enabled by anytime-anywhere communications. So by 1992 we had all the ideas and we were trying to build the thing. That was really hard. And we kept slipping. The schedule kept slipping. And the partners kept getting more and more anxious.

Andy Hertzfeld: At the same time, we found out that our leading benefactor, our father, decided to kill us.

Marc Porat: I remember a board meeting where we were laying out all the secrets and all the plans. In that meeting John Sculley was taking copious notes, word for word almost, just huge amounts of what was being said, and Andy turned to me and said, “What’s up?”

Andy Hertzfeld: The Newton project had run aground. It wasn’t going to work and it was going to cost $10,000 instead of $5,000. You couldn’t get the display and it was too complicated and it was failing. And with the Dynabook vision of the Newton failing, he decided that Newton should instead copy Marc’s vision and make something based on Marc’s prototype. It should ft in your pocket at a low price point.

Marc Porat: That was really a problem. Why did Apple not just put all their weight behind Magic? Why did they have to hedge their bets? Sculley set up the competition for essentially the same IP and the same market space.

Andy Hertzfeld: The Newton was supposed to cost $5,000. They remade it to cost $500. It was supposed to be the size of a notebook and it became the size of a postcard.

Obviously, it was an existential threat.

Marc Porat: The design center of the Newton was handwriting recognition. Our design center was personal communication. Personally, I thought there should have been enough blue sky between them so they could coexist, but it was widely viewed by both the teams and by outsiders, for example our licensees and the media, that they were set up to compete with each other. That was the perception. And there was some bitterness about that.

Andy Hertzfeld: Sculley was on our board! It was a real betrayal.

The Newton debuted in August 1993, and it flopped. The main problem was the handwriting recognition software: It was not very good. But the fact that Garry Trudeau made the Newton into a recurring punch line in his nationally syndicated comic strip, Doonesbury, didn’t help much, either.

Mike Doonesbury: “I am writing a test sentence.”

Apple Newton: Siam fighting atomic sentry.

Mike Doonesbury: “I am writing a test sentence.”

Apple Newton: Ian is riding a taste sensation.

Mike Doonesbury: “I am writing a test sentence!!”

Apple Newton: I am writing a test sentence!

Mike Doonesbury: “Catching on?”

Apple Newton: Egg freckles?

Apple had rushed to market and paid the price. General Magic, meanwhile, wasn’t going to make the same mistake that Sculley did. Instead, they made the opposite mistake. Pursuing perfection, Magic fell several years behind.

Marc Porat: AT&T was late; they could not get their network done. Sony was late, they could not get the consumer electronics piece done. We were late, because we were perfectionists. We were late because we pushed ourselves to the limit. We felt a lot of pressure internally because we were late, and we had to synchronize our releases with how ready our partners would be. Everyone was late. Two years late.

Michael Stern: We missed Christmas of ’94, so we really thought, Okay, next year.

Amy Lindburg: The frst thing that we shipped was the Sony Magic Link.

Andy Hertzfeld: And as soon as the Magic Link came out I gave one to Steve.

Marc Porat: Because it was inspired by the same kinds of things that the MacOS was inspired by, it was built by the same people, it was designed by the same graphic artist.

Michael Stern: And then as soon as we shipped we went on the road show for the public offering.

Marc Porat: I spent 80 percent of my energy managing the founding partners. We needed to be clear of them, and an IPO would get us enough money where we did not actually have to be so beholden to them. The IPO hinged on getting everything organized, and of course AT&T was the last one in, to deliver what they needed to deliver, and then we were off to the races.

Steve Jarrett: We’d already sold a significant amount of stock to these large partner companies, and we had a bunch of licensing revenue coming in, so the company looked superstrong on paper. And so when we went public in 1995, it was one of the first internet IPOs in the sense that we had a particular price and then we opened way, way above the S1 price.

Marc Porat: We were priced at $14, opened at $32, and took in tons of money. So the IPO as an event was very successful. But then the Magic Link sales were not good, and we said to ourselves, “Oh man, this is not going to go well.”

Andy Hertzfeld: We were hoping to sell a hundred thousand of the first Sony devices, but they only sold like fifteen thousand.

Steve Jarrett: The hardware was too large. The battery life wasn’t great. They were very expensive. The first Sonys were $1,000. Remember, these weren’t mobile phones. These were devices that, to communicate, you had to plug in a telephone cable.

Megan Smith: The devices were doing so many new things that nobody knew what we were talking about. Why would they want something like this?

Amy Lindburg: We were designing a product for Joe Sixpack—literally they would call the customer Joe Sixpack—and the trouble is that at that time Joe Sixpack didn’t have e-mail! It was too early.

John Giannandrea: One of the great Silicon Valley failure modes is “right idea—way too early.”

Amy Lindburg: And then the internet started to emerge.

Marc Porat: One day, as I recall, someone brought in something called Mosaic, and they said, “This is the future.” I said, “Okay, what is it?” We loaded it up and it crashed immediately. “Well, why is this the future?” “Just watch, just watch.” He put it back up.

John Giannandrea: We downloaded this thing and people were crowded around the workstation—I think it was a Silicon Graphics Indigo—and we were like, “Look at that!”

Marc Porat: We were looking at a really early browser, and there was already awareness inside the team that we had to go internet. We knew that release 2.0 would have to be an internet machine. The question was, can we ship the first one and still have enough time, money, energy, and stamina to get to the second one?

Michael Stern: We have no revenue. Things aren’t working. The partners start bailing. Things are getting pretty ugly.

Steve Jarrett: We kept taking the first-generation hardware to trade shows and kept getting asked, “Oh, does it have a phone inside of it?” It became really clear that the next product that we should try to build should actually be a cellular phone.

And so Andy and the other engineers started to make a smartphone—a handheld cellular phone that was running our software. Again, remember, like this is before digital cellular existed, so SMS didn’t exist and you couldn’t send data over cellular. And so, they built this very early prototype which had wireless web browsing.

John Giannandrea: So there were two devices. There was the device being built for Sony. And everybody knew that it was a dog. I was working on the second product, which was going to be cheaper, faster, have better battery life …

Marc Porat: Andy and Bill demoed a Magic machine, which was in a format like an iPhone, and they said, “So this is what we are going to ship next. It is a phone, and you can see all the Magic Link icons on it, and let me show you how it works.” They go through contact the manager, the telephone, sending e-mails… the works. That was iPhone form factor and that was iOS functionality in 1995. We were very excited about it, and they said that this is the next thing that we are going to do. That was for 1997.

Steve Jarrett: But was this actually physically possible for us to do? It was clear that was going to take years to build a super compelling product like that. For me, that was the sign. That’s when I left the company.

John Giannandrea: I quit. Part of it was realizing that we had a better product and we weren’t going to ship it.

Marc Porat: We were one year away from it. We kind of ran out of gas, we ran out of steam, and ran out of the will to take the next step. Most of us were exhausted, for our own reasons. Andy had probably worked eighty hours a week forever. We were just plain tired.

Michael Stern: After his first big surge of creativity, Bill kind of checked out. Andy was running engineering for three years. He had just had enough by ’95.

Marc Porat: It was a physical fatigue, when you keep something alive for five years on a vision and on just the raw energy of passion to do something amazing, five years is a long time to keep that going, and you want some validation at the end of it.

Michael Stern: So everybody leaves. I stayed on because I felt some loyalty to Marc. It was really sad and ugly. Everyone who touched the project at their respective companies—at Motorola, at Sony, and AT&T—their careers were wrecked.

Because these companies had gone public saying, We’re doing the next big thing. We’re creating the future here! And then it crashed. It was a train wreck.

Marc Porat: Engineers do things because they want millions of people to touch it. That is the ultimate reward for a top-level engineer. And when millions of people do not touch it, where is your source? Where is your juice? Where is the passion coming from? Where does the juice come from to take it to the next level? You need some affirmation; companies need some affirmation to keep going.

Michael Stern: The company failed—we didn’t ship a product that people wanted to buy. But this cadre of brilliant kids in this incredible pressure cooker went on to do amazing things and create the world that we now take for granted.

Megan Smith: There was this group at Apple that apprenticed with Steve Jobs, Woz, Mike Markkula, and all that crew, and learned. And then at General Magic they became the wizards and then we’re the apprentices. Phil Goldman and Zarko and Tony, Amy—we were the junior group to this senior group.

Amy Lindburg: Tony went on to do the iPod and the iPhone.

Steve Perlman: Phil Goldman and Bruce Leak both founded WebTV with me. Andy Rubin joined later.

Amy Lindburg: And then Andy went on to do Android. And Zarko spun out the software modem—which was the first modem ever in software in the world.

Michael Stern: Megan left Magic and went to San Francisco and founded PlanetOut, the first online community for lesbians. It became very successful and of course she ended up as the CTO of the United States of America. Not bad!

Amy Lindburg: General Magic was the kind of company where a guy who is going to be a billionaire in a couple years didn’t even rate a window cube.

Chris MacAskill: Pierre Omidyar was running AuctionWeb on his Mac IIci in his cubicle.

Pete Helme: Supposedly the idea came at a local Chinese restaurant while he and a bunch of General Magic guys were talking, you know, “Wouldn’t it be great to sell stuff on the internet—and what about an auction format?”

Michael Stern: So Pierre came to me when I was the general counsel in 1994 and said, “I’ve created this little electronic community. I’m getting people to talk to each other about trading tchotchkes. We’re creating traffic on the network and getting people into a community. That’s kind of in our sweet spot, isn’t it?” That was General Magic’s thing: the whole notion of electronic community. I said, “That’s the stupidest idea I’ve ever heard! If you want to do it, bye, see you later.” That was eBay.

Amy Lindburg: Everything came out of General Magic like just a big explosion.

Michael Stern: iPhones, social media, electronic commerce, it all came out of Magic. That’s the story.

Excerpted from Valley of Genius: The Uncensored History of Silicon Valley (As Told by the Hackers, Founders, and Freaks Who Made It Boom) by Adam Fisher.