What follows is an excerpt from Sam Anderson’s new book Boom Town: The Fantastical Saga of Oklahoma City, Its Chaotic Founding, Its Apocalyptic Weather, Its Purloined Basketball Team, and the Dream of Becoming a World-Class Metropolis. Anderson (a former book critic for New York) argues that humble Oklahoma City — 27th most populous city in the country, home of the American Banjo Museum — is, in fact, one of the most secretly interesting places in the world.

That claim might seem outlandish, but the historical evidence backs it up.

Consider, for instance, OKC’s bizarre origin story. It reads less like an episode of actual history than a spaghetti western written by a faulty algorithm. The place was founded on a single afternoon, in an event called the Land Run, during which a formerly empty patch of prairie became a city of 10,000. The chaos that ensued was so alarming that the U.S. government never allowed anything quite like it to happen again. This formative absurdity set the tone for everything that followed: the shootouts and power grabs and even — eventually — NBA basketball. Today, OKC remains a city of booms and busts, of grand gambles, huge wins, and crushing losses. It is a place where oil executives have been reduced, overnight, to mowing people’s lawns, where the sky spawns tornadoes wider than Manhattan, and where humans as different as Kevin Durant and Russell Westbrook improbably co-existed and thrived.

And it all started on a single day.

When does a city begin?

In most cases, we have no idea. We are forced to invent origin stories: wolves raising twins, eagles carrying snakes. The volcano god belches: civilization.

We want the birth of a city to make sense, to be grand. We want it to lend its citizens meaning. But the reality is almost always far less dramatic. Cities creep into existence, like algae. (Lewis Mumford: “The city is a fact in nature, like a cave, a run of mackerel or an ant-heap.”) It’s silly to talk about beginnings. No one is standing there firing a starting gun. There is no primordial boom. It happens in slow motion, over generations, by accident. Even if we do happen to know the general outlines — a European explorer found a promising bay, and eventually other Europeans followed him there — almost all the specifics are lost. We’ll never know what most cities were like during their very first hour, minute, second. It doesn’t even really make sense to ask. Cities are not microwave popcorn.

Unless you are talking about Oklahoma City.

Oklahoma City is microwave popcorn. It has a birthday: April 22, 1889. Noon. Precisely at that moment, history flipped a switch. Before, there was prairie. After, there was a city.

Oklahoma City was born in an event called, with extreme dramatic understatement, the Land Run. The Land Run should be called something like “Chaos Explosion Apocalypse Town” or “Reckoning of the DoomSettlers: Clusterfuck on the Prairie.” It should be one of the major events in American history. Dramatizations of it should be projected onto IMAX screens with 3-D explosions, in endless loops, forever. Every time you walk into a mall, you should be accosted by fuzzy-headed Land Run characters shouting, “What is America?!” “What does America even mean?!” Because the Land Run was, even by the standards of this very weird nation, absurd. It was a very bad idea, executed very badly. It would be hard to think of a worse way to start a city. Harper’s Weekly, which had a reporter on the ground, called it “one of the most bizarre and chaotic episodes of town founding in world history.” A century later, the scholar John William Reps reviewed the evidence and concurred. The founding of Oklahoma City, he wrote, was “the most disorderly episode of urban settlement this country, and perhaps the world, has ever witnessed.”

It’s hard, today, to imagine the scale of it — the idea of so many people, wanting so desperately, to move to Oklahoma. But it happened.

Or rather, it was made to happen. A place in the middle of America, on the brink of the 21st century, does not simply found itself. It took force and blood and betrayal and good old opportunistic populist jingoism. For many decades, the area we know today as the state of Oklahoma — the pot-shaped chunk of map between Texas and Kansas — was something else entirely. It was called, simply, “Indian Territory.” As American citizens took over every last pocket of the continent, the U.S. federal government had forced indigenous peoples out of their ancestral homes and into this empty patch of the Great Plains. Oklahoma was the endpoint of all the many Trails of Tears. The Choctaw, the Cherokee, the Chickasaw, and dozens of others — sea people, swamp people, forest dwellers, nomads — moved out into the sprawling grasslands. The area was, officially, off-limits to white settlers. It was promised to the tribes as long as, to quote the famous treaty, “grass shall grow and water run.”

The betrayal of that promise did not take long. It began right at the center of Indian Territory, when two tribes, for complex reasons, sided with the South during the Civil War. As punishment, the U.S. government seized their land and gave it to nobody. The area — about 2 million acres, or roughly 5 percent of the state of Oklahoma as we now know it — came to be called the Unassigned Lands. It was a vacuum, nearly half the size of Connecticut, right near the center of America.

Residents of the neighboring states — Arkansas, Missouri, Kansas, Texas, Colorado — noticed that emptiness. They became obsessed with it. They lusted after it. They gave it a name: Oklahoma, Choctaw for “red people.” Some managed to convince themselves that Oklahoma was their destiny, that they were somehow entitled to it. They pressured Congress and propagandized in newspapers.

The surrounding tribes, of course, vehemently objected. The Civil War had blown a hole in the center of Indian Territory, but the rest of it was still allegedly guaranteed forever. Allowing white settlers to pour into the Unassigned Lands would threaten the integrity of everything that surrounded it. Who could say what chaos might follow? Congress deliberated. White settlers lobbied.

Finally, predictably, the settlers got their way.

Congress agreed to open Oklahoma — the Unassigned Lands at the center of Indian Territory — for settlement. There was no orderly procedure for doing so, no process. The authorities would simply fling the land open and let everyone go at it. The rules were minimal and extremely hard to enforce. You could claim 160 acres out in the country or a small lot on a townsite. All you had to do was get yourself there, hammer in your stakes, and fight off competitors. Oklahoma would be, more or less, a free-for-all.

When President Harrison signed the document announcing the date of the Land Run — April 22, 1889 — his signature sent a bat signal out over the end of the nineteenth century. Oklahoma was a gift: a free chunk of America for anyone who needed it. But it was also an emergency: It was free only to those who could get there first. The hysteria spread worldwide. European ports, from Liverpool to Hamburg, teemed with sudden (as they were sometimes called) Oklahomaists. There were Scots and Swedes, bands of Mormons from Utah. Classified ads appeared in the newspapers of Chicago and New York calling for meetings of potential settlers.

In southern Kansas, the villages near the border of Indian Territory exploded into temporary boomtowns. Suburbs of tents spread in every direction: tent casinos, tent brothels, tent churches, tent hotels, tent restaurants, tent newspapers. Swindlers arrived to siphon off the settlers’ money. Their victims had to go begging in the shantytown streets, or they just gave up and went home, not only ruined, as they had been when they’d arrived, but now double- or triple-ruined. Something like 100,000 settlers showed up to wait for the starting gun — roughly the entire population, at the time, of Indianapolis. It was far too many people for the amount of good land available, but from the very start, Oklahoma was an idea that far exceeded its reality.

The border of Oklahoma was as tenuous as a border could be: more than 300 miles long and in many places unmarked. Where it was marked, it was often only with barbed wire or a creek or a pile of stones. It was impossible to fully patrol. Rumors circulated about nefarious schemes. Cheaters, it was said, planned to sneak in early and burn the railroad bridges so no one could follow. A French hot air balloonist planned to hover just over Oklahoma until noon, then descend onto his favorite spot before anyone else had a chance.

The only thing everyone knew for sure was that they needed to get to Oklahoma first. Time started to twist into itself. “Every man wanted to be 15 minutes ahead of everybody,” one observer wrote, “and not 15 minutes behind anybody.”

The day before the Land Run was Easter Sunday. All day, streams of wagons arrived at the border. The settlers carried civilization with them in tiny pieces, like ants, in order to collectively reassemble those pieces in Oklahoma. They brought all they could afford: shovels, forks, saws, underwear, crackers, bologna, bacon, canteens, dairy cows, heavy machinery, libraries. Some settlers came alone, others as part of strategically assembled teams. Everyone in these roiling crowds was exhausted but giddy. The normal rules of life seemed to have been suspended. Men marched around the temporary camps hooting and firing guns. They wrestled, raced horses, played baseball, sang hymns, and shot recreationally at prairie dogs.

When the settlers woke up the next morning — at least those who had managed to sleep — it was suddenly the day itself: April 22, Land Run Day. The Oklahoma skies were a perfect blue. Troops led the pioneers to the starting line — the membrane inside of which a new civilization was waiting to be born.

Oklahoma was about to happen.

All around the border of the Unassigned Lands, time collapsed into a single moment — noon.

If you think about the concept of “noon” hard enough, like a stoner or a phenomenologist, it starts to get fuzzy around the edges. Is it a clock fact — 12:00 — or is it an astronomical fact: when the sun is directly overhead? The settlers, that day, thought very hard about such questions. Wristwatches along the border were found to differ by as much as half an hour. Unsupervised settlers went with whatever version of noon seemed most advantageous. They squinted at the sun, trusted their guts, and made a run for it. In some places, there were official signals. On the western border of the Unassigned Lands, the military fired its howitzers — loud little snub-nosed cannons — to give people permission to run. In the south, 5,000 people stood in the middle of a river, trying not to sink into the quicksand, waiting for a soldier to blow his bugle. In the north, soldiers held a rope taut across the border to keep the settlers back.

Eventually, non-synchronously, the various noons came. The Land Run began. The people poured in. The moment the bugle touched the bugler’s lips, before he’d even squeezed out a note, the settlers burst through the rope. Oklahoma was born. Rich men rode racehorses they’d bought for enormous sums only days before. Farmers rode broken-down mules. A handful of eccentrics pedaled bicycles. Poor people walked. All over Oklahoma, the people came.

Some settlers stopped just across the border, claiming the first open land they could find. Most, however, raced deeper into the territory. The country was rough, and the settlers’ wagons weren’t designed for it; they hit dry creek beds or buffalo wallows and busted apart. The drivers flew out, got up, limped on. Before long, the prairie was covered with wrecks. Spooked horses threw their riders. At least one man fell and broke his neck. Other horses died of exhaustion. One settler fired his gun to speed up his horse but accidentally shot and killed another settler. It was absolute chaos, an explosion of humans. Actually, it was like a reverse explosion: tens of thousands of people who had been scattered across the globe, who had never had any reason to think they might be connected in any way, were suddenly thrown together in a dense core in the middle of America.

Out on the site that would eventually become Oklahoma City, federal troops waited. This was a perfect place for a hypothetical town, right where the railroad tracks crossed a river, and it drew settlers like a magnet. But there was time. The border was 15 miles off in every direction, in some places much farther, so even a man riding a racehorse at reckless speeds from the nearest point would take roughly an hour to arrive. The troops milled around in the wide open land, near the railroad tracks and the burbling river, among all the wildflowers, and prepared themselves to wait. They could have reasonably expected, at that moment, one last hour of silence.

They would have been wrong. The bugle notes had yet to fade when, like some kind of ancient creation myth, the empty landscape sprouted people. It was an ambush of settlers. “Almost like the rush of jack rabbits from cover,” the historian Stan Hoig describes it, “men suddenly appeared out of the long grass around the depot area, bounding here and there. They dropped from the leafy branches of trees; they crawled out of and from under freight cars; they sprang from gullies and bushes; they poured from the few buildings at the station; and they suddenly came galloping up on horseback from nowhere.” These were, in the lingo of the times, Sooners, or Moonlighters. We would call them cheaters. They had been waiting for this moment for years. Some of them had been hiding out in the wilderness around the station, illegally, for weeks or months, living in holes or bushes or improvised huts, dreaming of the glory of Oklahoma City. Some had leaped off moving trains just the night before, thumping and rolling over the prairie at high speed, breaking various bones — a physical tax on early entry that they were perfectly willing to pay.

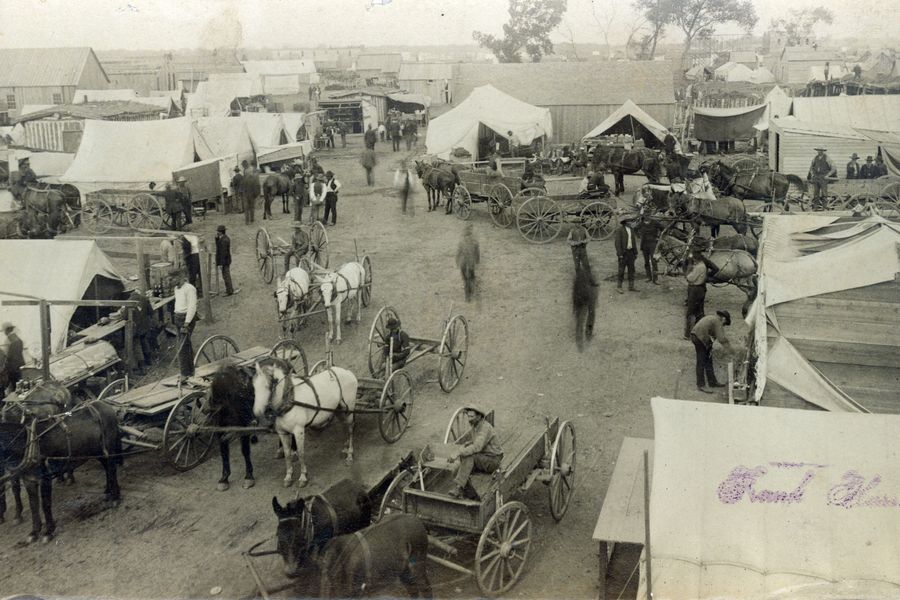

At the sound of the bugle, all of the cheaters came running. The land was free, they knew, only for those who got there first. There weren’t nearly enough troops to stop them all, and there was too much chaos to even know whom to stop. An entire crew of surveyors popped out of the wilderness, complete with their equipment — chains, poles — and started organizing the prairie on the run, marking off lots and blocks on a completely theoretical Main Street. Twenty minutes after the bugle sounded, there were already 40 tents set up. By 12:45, 15 minutes before the troops would have expected to see their very first settler, the city’s best spots had all been taken. By the end of the day, tents would stretch to the horizon — it looked, according to Harper’s Weekly, like “a handful of white dice thrown out across the prairie.” The wildflowers were crushed, the soil torn up. The native animals, frogs and ducks and prairie chickens, had scattered. In a matter of hours, one settler wrote, “the natural beauty of the scene was completely obliterated, beyond recognition or hope of repair.”

This was the beginning of Oklahoma City. The town had an almost instant population of 10,000 with no organization whatsoever — no government, no official limits, no laws, no framework for making laws, no legal entity on behalf of which to even build a framework on which to eventually make laws. There was no state of Oklahoma. There was no historical precedent. It was pirate civics. The men who were supposed to be helping the troops, the U.S. marshal and his deputies, were busy instead grabbing the best land for themselves. Technically, government officials were not allowed to claim land, but practically it was a free-for-all. (Most of the deputies had signed on only for this purpose, and they took the bugle call as a signal of their resignation.) The railroad station’s postmaster left his post office — a converted dirt-floored chicken house — and claimed 160 acres right on the edge of town. One military man who’d been stationed just outside Oklahoma City to guard against cheaters spent the weeks leading up to the Land Run building a house on rollers so that he could move it, at noon, to his favorite site in the area. People claimed land not only for themselves but for distant relatives who never intended to come to Oklahoma and for fictional characters they invented on the spot. The settlers of Oklahoma City explored the nearly infinite gradations between cheating and non-cheating. One man who’d sneaked onto the townsite early soaped up his horse to make it look foamy, as if he’d just galloped a long way. Another shaved off his beard and dyed his mustache black so no one would recognize him.

The first legal settler of Oklahoma City, by most accounts, was a rancher named William McClure, one of the major landowners in the territory east of the Unassigned Lands. He came riding into town just before 1:00 p.m. — an inhumanly fast trip. It turned out that McClure had paid some of his cowboys to go into the territory ahead of time and leave a relay of fresh horses along the trail. When McClure’s horse got tired, he jumped onto a new one. When that horse got tired, he switched again. He had found a way, without technically cheating, to outrace time.

Just after 2:00 p.m., in the middle of all that chaos, the first train of settlers pulled into Oklahoma Station. It was 24 cars long. Settlers were hanging off the sides and clinging to the roof; heads and arms were sticking through the broken windows. Eyewitnesses said it looked like a giant centipede wriggling toward the city. As the train began to slow down, passengers came spilling out from all sides. They hit the ground, rolled, and went sprinting for lots. According to one settler, “The whole country where the city now stands was black with a surging, crowding, running, yelling mass of humanity.” “It seemed,” another would remember, “as if some thousands of human beings had gone mad.” The townsite had only one well, and an enterprising settler cornered it immediately, standing on top of it, guns drawn. He set up a lucrative business charging five cents per drink, an exorbitant price that the people, their throats clogged with prairie dust, had no choice but to pay. Eventually, the soldiers seized the well and returned it to the public.

Settlers claimed every available scrap of land, without regard for how the city might eventually function. “Every stake driven represented a gamble,” one of them wrote. “It might prove to be on a lot, when lots should be established, and with almost equal chance it might prove to be on a street or an alley.” One woman staked her claim in the middle of the railroad right-of-way. It took the soldiers some time to convince her that, if she chose to build there, her property would be rumbled to the brink of destruction, over and over, on a regular schedule, for the rest of her natural life.

All day, settlers poured in and jockeyed for plots. When they found a bit of space, they set about improvising crude shelters. At dusk, as if by agreement, everyone suddenly stopped working. They laid down their hammers and rifles, took a break from jockeying for plots. They made campfires. It was the end of what would have been, without exception, the strangest day of everyone’s life. The first night in Oklahoma City must have been profoundly disorienting — some combination of sleepover, refugee camp, Super Bowl tailgate party, sit-in, and Visigoth raid of imperial Rome. These former strangers had become, in no time at all, a single town.

Oklahoma City, from that point on, would grow in fast-forward, a parody of a normal city. Its first year would see contested elections, brawls in city council meetings, and the death — by shooting — of the mayor. Within days there were wooden houses, slapped together quickly out of preassembled frames; within months, brick warehouses and shops; within years, grand stone mansions; within decades, skyscrapers, convention centers, sports arenas — all the precursors of the city’s 21st-century form. Today, OKC is the home of the Thunder, an honest-to-God NBA franchise, as well as a powerful memorial to the bombing of its federal building in 1995 (the deadliest attack on U.S. soil between Pearl Harbor and 9/11). It boasts an 850-foot glass skyscraper that looms nearly twice as tall as any other structure for 100 miles in every direction — a comically huge monument to the oil and gas money on which the local economy was built.

That first night, however, it was only dirt. Dirt on the ground, dirt in the air.

The soil, having lost the anchor of its plants, blew around freely in the wind.

The day had been hot, but the night was uncomfortably cold. Fortunate settlers had tents. Those who didn’t just lay on the ground — strangers, side by side, packed together for warmth. Men walked together through the night, talking. New residents continued to arrive in the dark.

As Oklahoma City struggled to settle down to its first night of sleep, something strange happened, an incident that everyone present would remember for the rest of their lives. Between 10:00 p.m. and midnight — accounts vary — a man’s voice suddenly penetrated the silence. It was deep, slow, and loud enough to carry all the way across the new city, over the tents, the railroad tracks, the cottonwoods, the river, to every one of the 10,000. The message it carried was clear but mysterious. “Oh, Joe!” the voice called out. “Here’s your mule!” This phrase hung in the air, not explaining itself, until suddenly another resident echoed it, every bit as loud: “Oh, Joe — here’s your mule!” The voices crossed, and then other settlers started joining in. “Oh, Joe!” they called. “Here’s your mule!” It turned into a kind of game. Soon the landscape filled with voices shouting the nonsensical mantra, louder and louder: “OH, JOE — HERE’S YOUR MULE!” On a hill a mile from town, federal troops heard the call, and they joined in, too. It was coming now from everywhere, out of sync, overlapping. The words didn’t matter anymore; the particular man and his mule, if they even existed, didn’t matter — as far as most people knew, there was no Joe, there was no mule. The words were a closed loop, an incantation through which Oklahoma City was going to chant itself into existence. This was an experiment in civilization. The place was so new and precarious, so strange, that its residents had to shock themselves into community using whatever method they could find — the way a human body, freezing to death, tries to generate its own heat by shivering. Perhaps that crazy late-night shouting could create just enough of a bond to allow Oklahoma City to withstand the turbulence of the next several days, years, decades. It was later reported that “Oh, Joe — here’s your mule!” spread that night across the entire Unassigned Lands, across Indian Territory, more than 100 miles, all the way back up to Kansas, where most of the settlers had begun.

Adapted from BOOM TOWN: The Fantastical Saga of Oklahoma City, Its Chaotic Founding, Its Apocalyptic Weather, Its Purloined Basketball Team, and the Dream of Becoming a World-Class Metropolis Copyright © 2018 by Sam Anderson. Published by Crown, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC.