Postmortem analyses of the long, eventful career of Senator John McCain have often touched on his turbulent relationship with his political party. Yes, he was the GOP presidential nominee in 2008, but in 2000 he earned many intraparty enemies while coming close to upsetting the overwhelming candidate of the party Establishment and the conservative movement, George W. Bush, and ruffled many Republican feathers again after the election of Donald Trump.

Between his two presidential campaigns, however, McCain went through a period of such intense estrangement from his party and its president that he flirted with the idea of leaving it. It’s all but forgotten now, but had McCain taken one of two tempting gambles, it might have changed 21st-century political history in unpredictable ways.

The first occasion occurred shortly after that first presidential defeat, as Politico recalled last year:

In secret negotiations with then-Senate Democratic leader Tom Daschle, McCain plotted how he would depart the GOP. He was furious over the way the party establishment had treated him in the 2000 race for the Republican presidential nomination against the eventually victorious George W. Bush. And within weeks of Bush’s swearing-in as president in 2001, McCain told Daschle that he was looking for a way out of the GOP, probably by declaring himself an independent—a move that would have thrown control of the otherwise 50-50 Senate to the Democrats. The negotiations got far enough, Daschle later told me, that the two men discussed the logistics of the news conference at which McCain would make the announcement. “We came very close,” Daschle said.

As it happened, Jim Jeffords switched parties, giving the Democrats control of the Senate, making a McCain deal much less urgent. And then 9/11 came along, and like most politicians, McCain swallowed his grievances against Bush for a while.

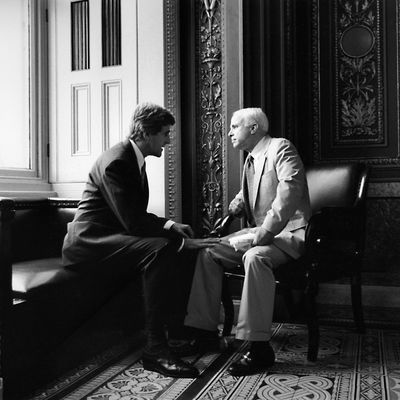

Those grievances didn’t go away, though, and as John Kerry began to nail down the 2004 Democratic nomination, his close relationship with McCain (they had bonded over measures to normalize relations with Vietnam, where both men had so famously served, and in McCain’s case, been imprisoned) led to growing rumors that they might outflank Bush decisively by running on the same ticket. In later years, McCain always got irritated when he was asked how far discussions about that possibility proceeded. Nobody doubted there were staff-level talks about it. But here’s what Kerry says about it now (in an advance copy I received of his soon-to-be-released memoir, Every Day Is Extra):

At the highest level of my campaign we had been approached by one of the people closest to John McCain. He suggested that John might be open to joining me. It was at least interesting—super-complicated, but interesting. I thought it shouldn’t be dismissed out of hand….

On a number of issues, from campaign finance reform to climate change to standing up to HMOs on behalf of patients, John McCain had very publicly broken with the White House. And I knew he had no patience for the lies about my military service. In fact, he had already defended me against the first attacks in the late spring, before the GOP made “Swift Boating” a big strategy and put huge money behind it. John could potentially have changed the electoral map, I believe, putting Arizona and Colorado in play. He was tested. He was tough. There were people around John who thought he would want the job, and they pressed me to consider him, in a way that made me think John was very interested. But in the end, despite the two of us sitting together a couple of times one-on-one and “talking about it without talking about it,” John couldn’t get over the hurdle of tearing up what had for him been a bumpy but lifetime association with the Republican Party. In essence, we flirted but we never went on a date.

It’s pretty clear McCain could have worked things out with Kerry if he had wanted to, and a poll in late May showed the two men leading Bush and Cheney by 14 points. But McCain backed away and soon endorsed the incumbent. It’s fascinating to think of how politics might have changed had McCain gone the other way.

McCain finally won the 2008 GOP presidential nomination after what amounted to a systematic repudiation of the bipartisan habits that made a Kerry-McCain ticket seem plausible four years earlier. As the Nation acerbically observed at the time:

[A]lmost everything that caused so many pundits to lose their heads and hearts to McCain during his first campaign has been jettisoned in the interests of securing the nomination of a party that is demanding–and securing–his fealty to one extremist position after another.

But he did at least consider one final mind-bending challenge to his party’s orthodoxies, according to every account of the 2018 election, including this one from the New York Times the day after he made his Veep selection:

For weeks, advisers close to the campaign said, Mr. McCain had wanted to name as his running mate his good friend Senator Joseph I. Lieberman of Connecticut, the Democrat turned independent. But by the end of last weekend, the outrage from Christian conservatives over the possibility that Mr. McCain would fill out the Republican ticket with Mr. Lieberman, a supporter of abortion rights, had become too intense to be ignored.

Facing a floor fight at the GOP convention, McCain knuckled under, and went with a very different kind of “maverick” and “game-changer,” Sarah Palin.

After 2008, McCain settled down and chose to remain, until the very end, an occasionally uncomfortable presence in the GOP rather than someone determine to change it or leave it. It is interesting, albeit fruitless, to speculate about the impact the Arizonan might have had if he had taken one crucial step beyond his party’s boundaries.