One morning earlier this week during executive time, President Trump tweeted out his assessment of the Russia investigation. “The Rigged Russian Witch Hunt goes on and on as the ‘originators and founders’ of this scam continue to be fired and demoted for their corrupt and illegal activity,” he raged. “All credibility is gone from this terrible Hoax, and much more will be lost as it proceeds. No Collusion!”

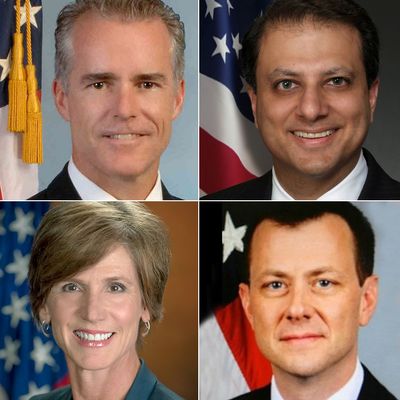

Amid this torrent of lies, the president had identified one important truth. There has in fact been a series of firings and demotions of law-enforcement officials. The casualties include FBI director James Comey, deputy director Andrew McCabe, general counsel James Baker, and, most recently, agent Peter Strzok. Robert Mueller is probing the circumstances surrounding Trump’s firing of Comey for a possible obstruction-of-justice charge. But for Trump, obstruction of justice is not so much a discrete act as a way of life.

The slowly unfolding purge, one of the most vivid expressions of Trump’s governing ethos, has served several purposes for the president. First, it has removed from direct authority a number of figures Trump suspects would fail to provide him the personal loyalty he demanded from Comey and expects from all officials in the federal government. Second, it supplies evidence for Trump’s claim that he is being hounded by trumped-up charges — just look at all the crooked officials who have been fired! Third, it intimidates remaining officials with the threat of firing and public humiliation if they take any actions contrary to Trump’s interests. Simply carrying out the law now requires a measure of personal bravery.

Trump has driven home this last factor through a series of taunts directed at his vanquished foes. After McCabe enraged Trump by approving a flight home for Comey after his firing last May, the president told him to ask his wife (who had run for state legislature, unsuccessfully) how it felt to be a loser. This March, Trump fired McCabe and has since tweeted that Comey and McCabe are “clowns and losers.” The delight Trump takes in tormenting his victims, frequently calling attention to Strzok’s extramarital affair — as if Trump actually cared about fidelity! — underscores his determination to strip his targets of their dignity.

Trump’s instinct for bullying also lay behind his unprecedented recent decision to remove the security clearance from former CIA director John Brennan and to threaten to do the same to a host of other former security officials. Trump cannot fire officials who have already left the government, but the gesture served as a kind of ersatz firing and contained all the familiar tropes. There were the absurdly hypocritical pretextual charges. Trump — who, in May 2017, literally handed sensitive intelligence secrets to Russian diplomats he’d casually invited into the Oval Office — was accusing Brennan of being an untrustworthy guardian of official secrets. The White House officially attributed this decision to Brennan’s “erratic conduct and behavior.” (One can only hope this line was an ironic joke inserted by a quietly subversive staffer in the press office.) Now that Brennan has lost his security clearance, he can be taunted as a loser and dismissed as a disgruntled has-been.

But while Trump’s apparent ongoing intimidation of the national-security apparatus is worrying, the truly terrifying exercise in power has been his purge of federal law enforcement. If a determined authoritarian president were to probe the system for weaknesses that would allow him to consolidate his power, the awesome authority of the Department of Justice is where he would focus. Either by instinct or by happenstance (we can rule out conscious planning), this is where Trump has arrived. The police powers of the state could, if corrupted, become a fearsome weapon both to hound the opposition party and to permit illegality by the president’s allies.

The Department of Justice has designed a credo, undergirded by a web of rules, to restrict it from interfering in politics. Those rules have proved pliable — indeed, Trump and his party began battering away at them during the 2016 campaign. The FBI’s famously Republican-leaning staff leaked promiscuously to Republicans such as House Intelligence Committee chairman Devin Nunes and, likely, Trump crony (and now lawyer) Rudy Giuliani. It was in part to head off a revolt from partisan agents, Comey later acknowledged, that he violated FBI norms by announcing a reopening of the investigation into Hillary Clinton’s emails in the waning days of the election.

Later, of course, Comey’s capitulation to Republican pressure became a pretext to fire him. The twisted genius of Trump’s purge is that it feeds on itself. Officials who resist Trump’s bullying can be fired for “bias,” but so too can officials who try to accommodate it.

Accommodation is the survival strategy employed by Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein, who has drawn Trump’s ire for failing to shut down Mueller’s investigation. Republicans have issued a series of demands to Rosenstein to let them inside the FBI’s investigation of Trump. Normally, the FBI keeps Congress away from ongoing political investigations, for obvious reasons. As House Republicans have demanded more and more access to the FBI’s and DOJ’s files, Rosenstein has beaten a series of retreats rather than take a stand and dare Trump to fire him. He may eventually be vindicated. On the other hand, it would hardly be shocking if Trump not only fires Rosenstein but uses his willingness to bend protocol as a reason to do so.

The last time the Republican Party controlled the Executive branch, it carried out a dry run for Trump’s current course of action, when the George W. Bush administration directed U.S. Attorneys to find and prosecute voter fraud. On the surface, it was a legitimate directive. Presidents are permitted to emphasize enforcement of some crimes they deem especially important — a Democratic president might (and usually does) order more-energetic enforcement of civil-rights laws, say. Voter fraud is a crime, so Bush was within his rights to ask the department to crack down on it.

The trouble is that, in actuality, voter fraud is so vanishingly rare it essentially does not exist. Republicans persist in denying this reality, much like they deny the reality of climate change, and have constructed a fantasy world in which Democrats routinely steal hundreds of thousands of votes. When the U.S. Attorneys reported that they found little or no voter fraud, Bush fired seven of them — violating tradition but not the law per se — and attempted to replace them with more-pliable figures.

But the episode came at the end of Bush’s second term, when Democrats controlled Congress and could hold investigative hearings, and when the president’s popularity had already sunk to toxic levels. The abuse of the department provoked a backlash that forced Attorney General Alberto Gonzales to resign. Order was restored, and the Department of Justice’s integrity was maintained, not because the Constitution proved invulnerable but because of a confluence of circumstances: The president was already losing the loyalty and support of his party, the opposition party controlled Congress and could use its subpoena power to expose wrongdoing, and some small measure of shame on the part of the bad actors compelled a course correction.

Things look different today. The president has a vise grip on the loyalties of his party base, and Republicans in Congress, for all their private misgivings, see crossing him as an act of career suicide. Shame has no more power over this administration than does Santa Claus. The remaining factor, control of Congress, hangs in the balance with the midterm elections. As does much else.

*This article appears in the August 20, 2018, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!