Over the last year and a half, there have been three things one could say about Donald Trump’s standing with the public, depending on which aspect you wished to emphasize:

(1) Trump is not very popular.

(2) Given his scandals and wildly unpresidential conduct in office, Trump is surprisingly popular.

(3) Given the public’s view of the economy, which is highly positive, Trump is extremely unpopular.

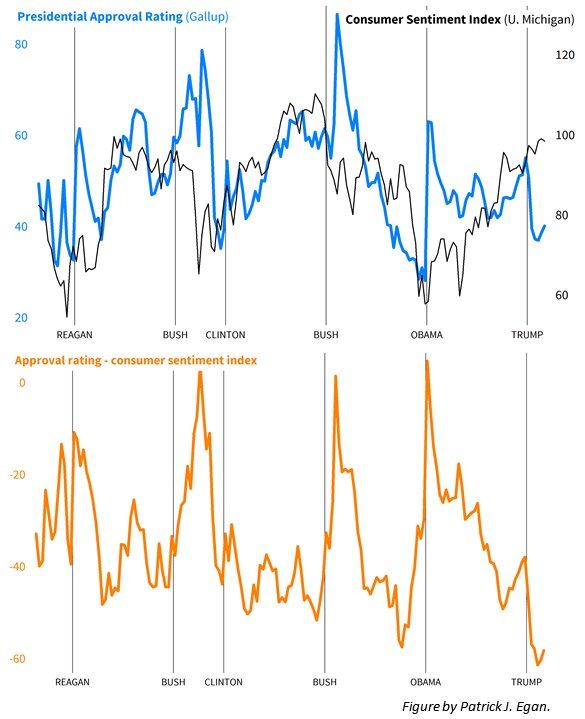

All three of these points are neatly brought together in a chart compiled by political scientist Patrick Egan, comparing presidential approval rating to consumer sentiment. The historically large divergence between the two illustrates just how badly Trump is underperforming given the buoyant assessment of the economy:

But beneath all these points, there is another question that has not yet been answered: Why is the public so positive about the economy in the first place?

The preferred Republican answer is that Trump has turned the economy around with his brilliant combination of deal-making, tax-cutting, and freeing Job Creators of laborious Obama-era regulation. There is no evidence whatsoever for this widespread claim. Ramesh Ponnuru and Michael Strain, two conservative writers, examine a wide array of economic data, and find the economy is performing no better now than it did in Obama’s second term. Overall economic growth is the same, and job growth is slightly slower. The Trump tax cut is supposed to spur more investment, which would increase incomes over the long run, but there is no sign of any increased investment so far.

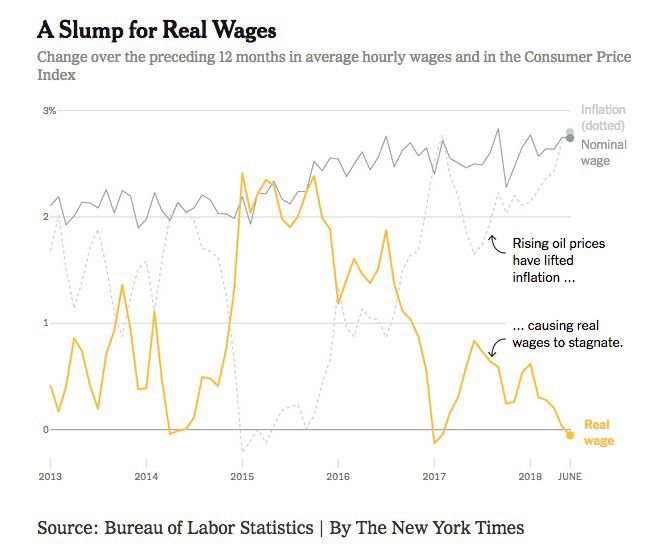

Indeed, by the measure people are most likely to feel directly, real wage growth, things have gotten distinctly worse over the last year. David Leonhardt shows that wages have (just barely) failed to keep pace with inflation over the last 12 months:

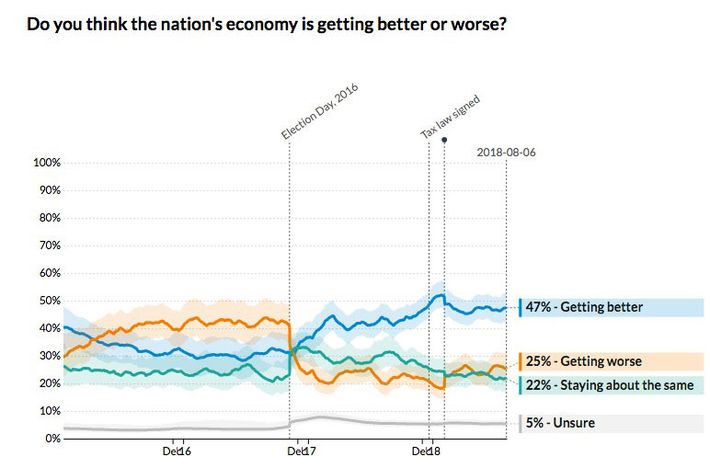

And yet, paradoxically, people think the economy has gotten better. Polls of public opinion show that perceptions have not changed because of any change in conditions. Instead, public opinion flipped immediately following Trump’s election:

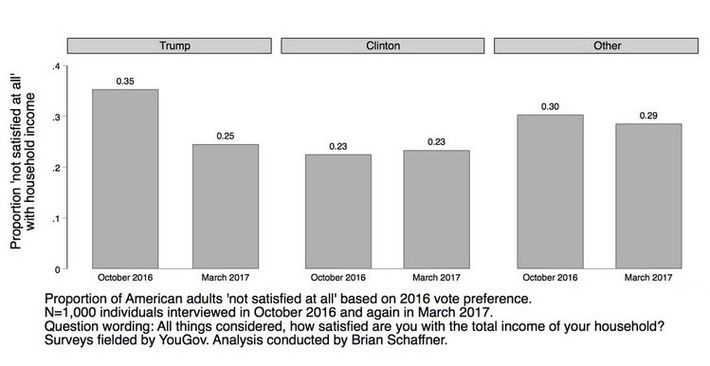

You might think public opinion is simply behaving in a partisan fashion, but that is only half true. In reality, Republican opinion has been heavily partisan, while Democratic opinion has not. Here’s a survey of Trump and Clinton voters’ levels of dissatisfaction with the economy, first before the election (on the left) and then shortly after Trump’s inauguration (on the right). Trump voters immediately became more positive in their assessments of the economy, while Clinton voters, rather than shifting in the opposite direction, stayed exactly the same:

As is the case with so many aspects of American politics, the story here is asymmetric polarization. Republicans enjoy the benefit of a base that is willing to give their president more credit for the economy than the opposing base. The same economy that is holding up the floor under Trump did almost nothing to lift President Obama or Hillary Clinton.

Progressive activists focused on the shortcomings of the recovery, believing that touting progress would ease up pressure on politicians to promote more growth, to the point where Democratic leaders treated the recovery as a political liability. Hillary Clinton’s economic message sounded more like an opposition party candidate than a successor. Here is the main passage assessing the economy from Clinton’s acceptance speech at the convention:

Our economy is so much stronger than when they took office. Nearly 15 million new private-sector jobs. Twenty million more Americans with health insurance. And an auto industry that just had its best year ever. That’s real progress.

But none of us can be satisfied with the status quo. Not by a long shot.

We’re still facing deep-seated problems that developed long before the recession and have stayed with us through the

recovery.

I’ve gone around our country talking to working families. And I’ve heard from so many of you who feel like the economy just isn’t working.

It is hard to determine precisely how much choice Clinton had in the matter. If she had given a more rosy assessment, progressive activists would have hammered her complacency. Even if they hadn’t, it’s not clear whether Democrats would have accepted a positive gloss on the recovery, or if the left’s political psyche is simply too inherently oppositional to permit such a celebratory outlook. Still, it is striking that the candidate who defeated Clinton is prepared to run for reelection boasting about an economy that his opponent had to dismiss.

Notably, the last Democratic presidential candidate to run on the heels of a long recovery presided over by his party — Al Gore in 2000 — also felt obliged to run as a populist change candidate rather than celebrating peace and prosperity. A party dedicated to representing the disenfranchised might have an unavoidable allergy to economic triumphalism. Indeed, this impulse might be a necessary spur for its leaders to demand more inclusive growth for those left behind. But the ease with which Trump has made the economy his principal political asset shows how the Democrats’ superior economic performance over the last quarter-century has done frustratingly little to boost their outcomes at the ballot box.