The mystery of why Donald Trump decided, midflight, to personally author his administration’s misleading response to the public disclosure that his son Donald Jr., Paul Manafort, and Jared Kushner attended a meeting with a cast of shady Russia-linked figures in Trump Tower remains a mother lode of the Russia investigation. His misdirection aside, the president has denied he knew about the meeting, its purpose, or that its participants were on a mission, and he’s declined to make himself available to Robert Mueller, the special counsel, to answer questions about it — or anything else related to Russia’s involvement in his electoral victory.

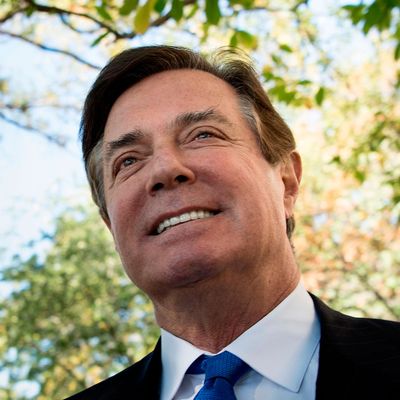

The reason Mueller’s inquiry exists in the first place is precisely that: to learn whether the Trump campaign actively conspired with the Kremlin to win an election. And now that the special counsel has, after much effort, extracted a guilty plea and a cooperation agreement with Manafort, a significant new avenue into Trump’s knowledge and state of mind just opened up in the investigation.

Trump has long believed that Manafort, who ran his campaign and had more than a few connections to Russia, would never flip or implicate him in any wrongdoing — an apparent acknowledgment that there was wrongdoing in the first place. But Friday’s development in federal court in Washington should put that belief to rest. Manafort has flipped in every respect, pleading guilty to two counts of conspiracy to defraud the United States and to obstruct justice that incorporate, by reference, the bulk of a laundry list of charges and offenses that he faced in Washington and Virginia.

Those criminal counts for bank fraud that jurors couldn’t agree on in his earlier federal trial? Mueller included them under “other acts” in a lengthy “statement of the offense” that lists all the ways Manafort ran afoul of federal law. Prosecutors spared no detail in the document, running through his decadelong lobbying campaign for Ukraine, which he kept hidden from the Department of Justice and netted him millions in unreported taxable income — and the ways he and associates tried to cover their tracks and not get caught in this grand scheme. Plus, it details exactly how Manafort, even as he was on Mueller’s watch for all these offenses, attempted to obstruct justice by trying to get witnesses to his misdeeds to massage their stories about his undisclosed lobbying work.

Under the plea agreement, and worst of all for Manafort, whatever assets he purchased with the wealth he made during his years as a lobbyist is bound to become property of the federal government — the special counsel’s office is seeking criminal and civil forfeiture of a number of his New York properties, bank accounts, and a life-insurance policy — all worth several million dollars and traceable to the conduct over which Manafort is now a convicted felon. Mueller followed the money, and now it’s gone.

As for what exactly Manafort has on Trump, and how useful he’ll be to Mueller’s unfinished work, that remains to be seen. But consider the case of Rick Gates for a moment: As Manafort’s onetime right-hand man, he cracked under the weight of the Russia probe and, seeing the writing on the wall, agreed to cooperate with the special counsel in February. Seven months later and one federal trial as a witness under his belt, Gates’s work is now bearing fruit against his former boss. And the more he continues to cooperate — now, presumably, in concert with Manafort — the more leniency he can expect from Mueller once his sentencing draws near.

Which is why it would be foolish to try to guess how much time in federal prison Manafort is expected to spend under his new plea agreement. The document itself calls for a sentencing range on both conspiracy counts of up to 262 months — or 20-plus years in the worst-case scenario. The burden is now on him to drive down that number by appeasing Mueller’s team and giving prosecutors what they’re looking for — not on Trump or a target in particular, but any leads or crimes that investigators may already be chasing. The more he gives them, the more the government may be inclined to show mercy.

Much like Gates looked out for himself and his own family, now it’s Manafort’s turn to watch out for himself and what little he has left. In light of everything he’s lost already, not even a pardon for Trump will give him his life back — or all the fame and fortune that the special counsel investigation sapped from him. One section of his plea even bars him from accepting “compensation of any sort” for anything related to his crimes — he can’t write a book about his ordeal, give speeches, or do anything that may make him a few bucks related to his run-in with Mueller. He can’t even lobby for himself anymore, after a lifetime of doing it for others.