A tax cut has a big first-order effect: the people whose taxes are reduced have more money, and the government has less. Since both of these — more inequality and higher deficits — are generally regarded as bad things, Republicans habitually dismiss them, and instead focus on second-order effects they predict will happen. The supply-side economic theory favored by most Republicans holds that rich people are exquisitely sensitive to tax rates, and their willingness to work or invest rises and falls dramatically in response even to small changes in tax rates.

This is why Republicans predicted upper-bracket tax hikes, like those passed under Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, would massively depress economic activity and raise less revenue than standard forecasts predicted. (It didn’t.) It is also why they predicted tax cuts passed by George W. Bush, and Republican governments in states like Kansas, Oklahoma, and Louisiana would yield far more revenue than predicted. (It didn’t.) They maintained the same belief about President Trump’s corporate tax cuts. The conviction is so strong that even the most moderate Republicans insist higher growth would cause revenue to rise rather than fall is response to the tax cuts.

In the ten months that have passed since Trump signed the tax cuts into law, the second-order effects have been undetectable. Nothing bad has happened to the economy; on the other hand, nothing especially good has happened, either. Growth and wages have tracked at about the same pace as before Trump took office. Republicans built a messaging campaign around one quarter of 4 percent growth, which they treated as unprecedented and now permanent development, ignoring the fact that the economy produced several such quarters under the Obama administration.

The Trump administration’s favorite rationale for cutting corporate tax cuts held that a lower rate would encourage American companies to bring back trillions of dollars in cash that they had stashed overseas. “Over $4 [trillion], but close to $5 trillion, will be brought back into our country,” promised Trump last month.

There is no sign of any such thing happening. The Wall Street Journal has conducted a review of the public filings of “108 publicly traded companies accounting for the vast majority of an estimated $2.7 trillion in profits parked abroad,” and asked each company what it was doing with the funds. The total amount of repatriation so far? $143 billion.

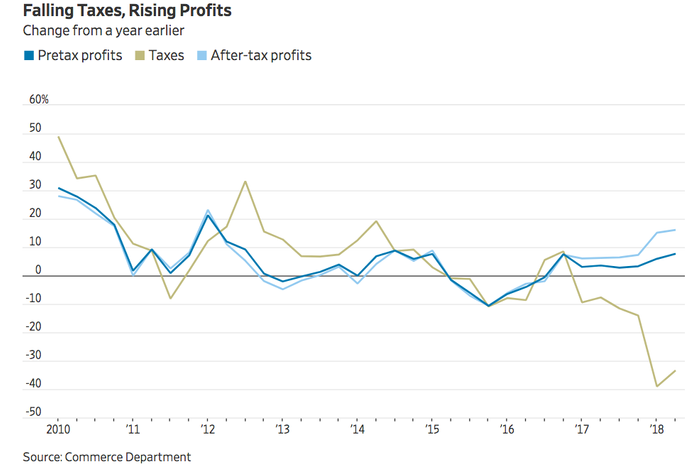

What has been very evident so far is the first-order effect. Just as critics of the tax cuts predicted, reducing the amount of tax corporations must pay the federal government has resulted in the government having much less revenue. Tax revenue tends to be highly sensitive to the business cycle, rising when the economy expands and collapsing during recessions. And yet, even as the economy has continued to grow in 2018, corporate tax revenue has dropped 30 percent over the last year.

What has happened to the extra money corporations got to keep due to lower taxes? First, corporations are enjoying much higher profit. Corporate profits soared 16 percent in the last quarter. As this chart from the Journal shows, pre-tax profit has risen some, but the main difference is that corporations are just paying much lower taxes on the money they’re making:

For the moment, the evident impact of the tax cuts is to widen the gap between what workers earn and what people who own companies earn:

What else is happening to all that money? Just as critics predicted, corporations are engaging in a massive binge of stock buybacks. Share repurchases rose 50 percent in the first half of 2018. “For the first time in 10 years, buybacks are garnering the largest share of cash spending by S&P 500 firms,” writes Goldman Sachs analyst David Kostin. Are corporations investing more? Yes, but mainly they are using their windfall to increase their own holdings.

If you believe the main problem with the economy President Trump inherited was an excess of redistribution, then the Trump tax cut was a helpful course correction. Its main measurable impact is a large lump-sum wealth transfer to business owners.