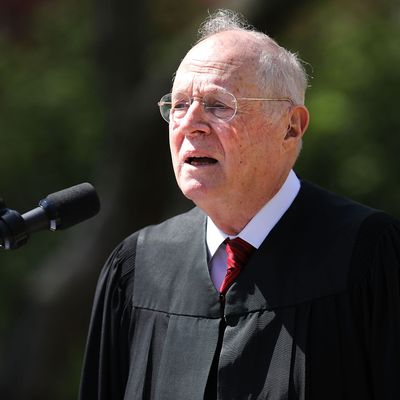

On Friday, Anthony Kennedy warned a crowd of high-school students that the 21st century has been characterized by “the death and decline of democracy.” Specifically, the former Supreme Court justice argued that maintaining “an enlightened civic discourse” was a precondition for “preserving democracy.”

Kennedy’s remarks were widely seen as a tacit criticism of the discourse surrounding his handpicked replacement. Less than 24 hours before Kennedy spoke to students in Sacramento, Brett Kavanaugh had declared himself the victim of a pro-Clinton conspiracy — while Democratic senators had asked him to define the word “boofing” — at a Senate hearing focused on the Supreme Court nominee’s alleged history of sexual assault.

According to reports, Kennedy personally recommended Kavanaugh to the White House, before announcing his retirement from the court early this year. It is unclear whether Kennedy believes that Democrats undermined an “enlightened civic discourse” by allowing Christine Blasey Ford to testify, or if he believes Kavanaugh did so by describing her testimony a “political hit job,” or both.

What is clear, however, is that Anthony Kennedy has a rather curious conception of democracy. By all appearances, the Supreme Court justice believes that keeping political arguments polite is indispensable for preserving “the rule of the people” — but protecting the voting rights of minority groups, and allowing elected officials to make policy on behalf of their constituents, is not.

The Voting Rights Act (VRA) of 1965 effectively inaugurated democratic rule in the United States. Before the VRA empowered the federal government to preempt racially discriminatory voting laws, the voter registration rate among white Americans was nearly 30 percentage points higher than that of blacks. After the VRA’s passage, that disparity fell to just eight percentage points by the early 1970s.

Four decades later, the act was still working as designed. Many states had never stopped trying to enact voting laws that were racially discriminatory in effect or intent — but thanks to the VRA, the Justice Department was able to nip such rules in the bud. In 2006, Congress reauthorized the VRA; 98 senators voted to renew the law — not a single one voted against it.

And then, in 2013, Anthony Kennedy (and four of his fellow unelected judges) decided to override the unanimous will of the Senate, and gut voting protections for racial minorities. In the majority opinion of Shelby County v. Holder, the conservative justices argued that the VRA’s formula for determining which jurisdictions were likely to discriminate on the basis of race — and were, thus, required to “preclear” any changes to their election laws with the Justice Department — was out of date. On this basis, the court freed every state and county in the nation to write election laws without federal oversight, unless or until Congress updated the VRA’s “preclearance” formula.

Even if one stipulates that Kennedy’s objections to the existing formula were sound, the logic of his decision remains confounding: If a jurisdiction is inappropriately subjected to preclearance, then it suffers the inconvenience of needing to consult with the Justice Department before revising its election laws. If a jurisdiction is inappropriately freed from preclearance, then vulnerable minority groups get disenfranchised. Surely, the latter prospect is a greater threat to Constitutional liberty than the former one.

Nevertheless, Anthony Kennedy chose to err on the side of disenfranchising black people. And, in the years since, America has witnessed a renaissance of racially discriminatory election laws. It is true that Kennedy and his colleagues left most of the VRA’s provisions in place. But without preclearance, red states (with threateningly large nonwhite populations) have succeeded in nullifying them by following a simple procedure:

1) Enact racially discriminatory voting laws.

2) Use those laws to win disproportionate power over state government.

3) When the federal courts finally get around to striking down those laws, enact new voting laws that discriminate against minorities in a slightly different way.

4) Use those laws to win disproportionate power over state government.

Which is to say: Thanks to Anthony Kennedy, elections in the U.S. are now routinely conducted under rules that prove, years later, to have been illegal. And the former Supreme Court justice does not consider this a threat to democracy — or, at least, not one on par with, say, senators being rude to each other.

Nor, for that matter, does Kennedy see any tension between maintaining democracy and allowing jurists like himself to veto other duly enacted laws, or place certain prerogatives of the economic elite beyond the realm of democratic contestation.

In every other country with universal suffrage, the government has determined that access to affordable health-care is a right of citizenship. In other words: When ordinary people have access to political power, they almost invariably ask their government to guarantee that they will not be denied lifesaving medical care simply because they aren’t wealthy.

Abundant polling data (and the GOP’s own messaging) suggests that a majority of Americans endorse that same principle. But for decades, the power of entrenched health-care interests — combined with the peculiar rules of our federal legislature (which make it profoundly difficult to pass major legislation) — prevented Congress from doing much of anything to achieve universal health care. Finally, in 2009, after Democrats won a landslide election that gave them a filibuster-proof majority in the Senate, Congress passed a law that significantly expanded access to medical care for non-affluent Americans.

And if Anthony Kennedy had had his way, five unelected lawyers would have nullified that achievement three years later. In National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, Kennedy joined Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, and Antonin Scalia in deciding that the ACA’s individual mandate was an assault on Americans’ liberty (while their decision to overrule Americans’ elected representatives, and, in so doing, condemn tens of thousands of them to preventable deaths, was not).

In other rulings, Kennedy decided that the American people had no right to regulate corporate spending on American elections, vetoed Arizonans’ attempt to limit the influence of such spending by providing candidates with public funds, legalized most forms of political bribery, and restricted the capacity of consumers and workers to sue corporations that abuse them.

Kennedy’s self-selected heir apparent, meanwhile, has suggested that much of the modern administrative state is illegitimate, and that judges like himself have a duty to gut regulatory agencies that have proven too popular to be reined in through democratic means.

To be sure, Kennedy and Kavanaugh do not self-describe their jurisprudence as anti-democratic (in fact, Kavanaugh has an affinity for portraying his opposition to the administrative state in populist terms). But many of their allies in the conservative legal community are quite forthright about their movement’s commitment to freeing private economic actors from democratic accountability. Michael Greve, a former AEI scholar and current professor at George Mason University’s Antonin Scalia Law School, made this point explicitly, in an interview with the New York Times in 2005:

As the administrative state ballooned during the 60’s and 70’s, judicial deference became even more pervasive: new independent regulatory agencies, from the Environmental Protection Agency to the Federal Communications Commission, began issuing a slew of regulations. To Greve’s dismay, much of the regulatory state is politically quite popular; even a Republican Congress, he acknowledged, seems unlikely to roll back most post-New Deal programs and regulations. “Judicial activism will have to be deployed,” he said. “It’s plain that the idea of judicial deference was a dead end for conservatives from the get-go.”

Anyone who has ever watched Question Time in the British parliament knows that rhetorical civility is not a prerequisite for democratic politics. By contrast, anyone who believes in racial equality, and acknowledges the reality that private enterprises effectively govern many aspects of American life, knows that voting rights — and the power of elected representatives to regulate the activities of corporations — are inherent features of self-government.

Anthony Kennedy may value the rule of law, and (a libertarian conception of) individual liberty. And he may fear that the increasing bitterness of partisan conflict in the U.S. threatens those ideals. But he cannot credibly lament the decline of American democracy over the past two decades —because he has done more to bring about such decline than virtually anyone in the United States.