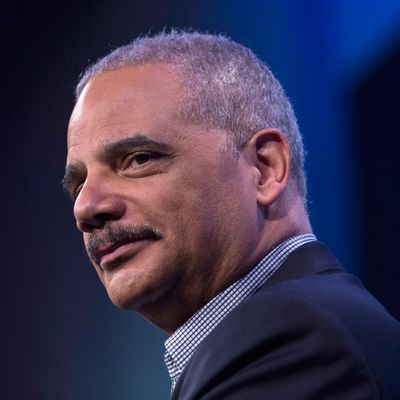

Eric Holder, the former US Attorney General, is, after Hillary Clinton, probably the most visible and politically active alumnus of Barack Obama’s cabinet. After leaving the Justice Department in 2015, Holder returned to his previous spot at the elite DC law firm, Covington & Burling. In the intervening three years, Holder has spoken out about voter disenfranchisement, courted endless gossip about 2020, and helmed a pair of high-profile investigations into Silicon Valley discrimination.

As Attorney General, Holder staked out a bold position on sentencing reform, instructed federal prosecutors to be lenient with non-violent drug offenses, and pursued racial discrimination investigations against police departments in a number of major cities. At the same time, the DoJ’s decision not to prosecute more than a handful of bankers, none high-level, after the financial crisis has been criticized by the left wing of the Democratic party. “The Justice Department, while I was there, and probably now as well, has been appropriately aggressive when it came to bringing these cases,” he says. “You have to understand that bringing a case against a high-ranking head of some financial institution — those are the kinds of cases that people go in to government to make.”

Since then, Holder has returned to Covington & Burling and conducted inquiries on behalf of Uber and Airbnb into issues of discrimination at both companies. He’s emerged as a strong voice on voting rights and gerrymandering issues, all the while giving conspicuous “wait and see” answers to questions about whether he’ll run for president in 2020.

The former attorney general recently spoke with Intelligencer about his recent activity — and his future. What follows is a version of that chat, edited and condensed for clarity and length.

I wanted to get your thoughts on the recent New York Times story about Rod Rosenstein, and how you reacted to the September saga over his status at the White House.

I’ve known Rod for close to 20 years, I bet. He’s a man of integrity. He’s a guy I have some significant policy differences with, but I think his tenure as deputy attorney general and the way in which he has conducted himself vis-à-vis the Mueller probe has been totally appropriate. If he is replaced, my concern is that we make sure that we have somebody in place who will give Bob Mueller the latitude and independence that he needs in order to do the full and complete investigation that I think the American people deserve. My hope is that Rod will not resign — as I said, even aside from our policy differences, I think it’s really critical that somebody like him be the one to whom Bob Mueller ultimately reports.

If you were in his situation, would you have done something like that? Would you have worn a wire, or considered it necessary for the security of the country?

I wasn’t in the room. But as I said, I’ve known Rod for 20 years. It really strikes me as hard to believe that he was serious, if he said it. I want to emphasize again that if he said it that he was serious when he did say it. That doesn’t strike me as Rod. It’s just hard for me to see that that was something that was said, and if said, was said seriously.

Let’s say he said it sarcastically. What do you make of the kind of environment that would lead a deputy AG, whose record you admire as much as Rosenstein — what do you think has to be the situation in the executive branch for him to even make a remark like that, and for that to land in the Washington Post or the New York Times?

Well, I mean, I don’t think there’s anything that’s surprising there, again, if he said it. And if it was even said sarcastically. You know, this president is a person who takes a variety of positions on the same issues. His positions are not necessarily factually based. And when you’re dealing with the matters that Rod and the Justice Department typically deal with, you need consistency, you need adherence to the facts, and obviously you need adherence to the rule of law. So, my guess would be that if he said so, you know, sarcastically, he might have been concerned about some of the things the president said to him about whatever the topics were that they were discussing.

Have you been in touch with him at all? Have you spoken with him or been in communication with him at all since he became the deputy AG responsible for the Mueller investigation?

Um [long pause]. I’d say no comment on that.

Understood.

You should not draw any conclusion one way or another; I’m just not, you know …

I’ve got it. I want to move onto your work on gerrymandering. This is the most visible public and political role that you’ve taken on since you left office. As a way to start, what were the ways in which you encountered gerrymandering and redistricting issues in your capacity as AG?

When we had a really vibrant and complete Voting Rights Act, the localities within states would do things for inappropriate reasons, designed to maintain a party in power, using inappropriate racial redistricting efforts. The Justice Department had the ability under the Voting Rights Act to reject those things. Then, of course, they could go to court and try to overrule the Justice Department. So, that would be the way in which I encountered gerrymandering, chiefly through racial efforts at gerrymandering when I was AG. As I was leaving the department and speaking to President Obama about what we might do in our post-government careers, I think we both focused on the problem of partisan gerrymandering and decided that that would be the focus of our post-governmental lives.

Did you see any overlap between partisan gerrymandering and racial gerrymandering?

Yeah. I think they’re different sides of the same coin. People who want to gerrymander, parties that want to gerrymander, do so in a variety of ways. Either through partisan means or through racial means. I thought it was interesting that in North Carolina, when they, Republicans down there, were attacked for gerrymandering along racial lines, they denied that, but said, “This wasn’t racial a gerrymandering; it was a partisan gerrymandering.” As if somehow that made it better. But no. You have seen gerrymandering done on inappropriate racial grounds. I guess a court in Virginia determined that what the legislature did there was inappropriate, and inappropriate racial gerrymandering was upheld by the Supreme Court.

It’s interesting because you bring up a good example of Republican gerrymandering, but the language you’ve selected, and the language of the NDRC campaign more widely, is nonpartisan. Except it’s objectively true that most of the gerrymandering around the country has been done to enfranchise the Republican party. So how do you square this being a nonpartisan, country-before-party project with the fact that this is a very nakedly partisan problem?

What I’d say is actually, “It is a partisan effort at good government.” That’s the way I describe it. There’s no question with the National Democratic Redistricting Committee, but we are trying to use the mechanisms that we have by filing lawsuits, by supporting reform efforts. And by reform efforts, I chiefly mean that we support the creation of independent, nonpartisan commissions to draw the line. That’s the best way to do it, to take it out of the hands of politicians entirely. So, we’ve filed lawsuits, we have the reform efforts, and then we have direct electoral support of people who are pledged to do redistricting in 2021 in a fair way. This is not an attempt to gerrymander for Democrats. I actually think that if this country has a redistricting in 2021 that is done in a fair way, not in a partisan way, but in a fair way, and makes it a fair battle between Republicans, conservatives, Democrats, and progressives, the Democrats and progressives will do just fine. But I really emphasize all the time that this is not an attempt to gerrymander on behalf of Democrats.

A lot of people are concerned about the 2020 Census. On a logistical level, there have been alarm bells since January 2017, but there’s also a lot of concern about the redistricting that happens following, and whether or not it can be really a fair and effective process. Are you concerned about that? Is the NDRC? And in your group’s efforts, are you seeking to address concerns regarding the Census?

Yes. Just very generally, I’m very concerned about the way in which the Trump administration will conduct the 2020 Census, and you’re right to draw that link. And people need to understand, there’s a direct link between the Census in 2020 and the redistricting that happens in 2021. I mean, the 2021 redistricting is dependent on a fair Census, but beyond that, people have to understand that the 2020 Census also determines how about $675 billion worth of federal money gets distributed to the state — everything from infrastructure to education, a whole variety of things that the federal government gives money to the states for. So, I’m generally concerned about the ways in which the Census might be done. Specifically, I’m concerned about — and the NDRC has filed a lawsuit against the Trump administration over this — the citizenship question. The Constitution only says that you’re supposed to count the people in the United States in particular districts or political divisions. And this is the first time a citizenship question has been included in the long-form Census since 1950. I think the evidence tends to show that that question was included to try to make sure that there’s an undercount in immigrant communities, and more specifically, in the Hispanic community. So, we have filed a lawsuit in Maryland on behalf of five plaintiffs, from five states. One of them is Cesar Chavez’s grandson. We’ve had some preliminary interactions with the courts there, and I actually think that that’s a lawsuit that is going very well.

What is the work that the NDRC is doing? There’s a PAC, there are these lawsuits being filed … Where would you say the most attention is being paid?

The NDRC is, as I said, a partisan attempt at good government. We have 12 target states, and we have 7 states on our watch list. We use four mechanisms to try to ensure the end of partisan and racial gerrymandering: filing lawsuits, supporting reform efforts, direct electoral support of candidates who will stand for fair redistricting, and grassroots mobilization to try to make the American people aware of the nature of this problem, and get them involved in the solution of it. I think people don’t understand that there’s a direct connection between partisan gerrymandering and the dysfunction that we see here in Washington, D.C., in our Congress, and the dysfunction you see in state capitals as well. When people are in safe, gerrymandered districts, the only concern they really have is a primary, as opposed to a general election. That pushes people further and further to the right — and, to be fair, further and further to the left. That makes cooperation far less likely. You see, therefore, gridlock and dysfunction. You don’t see much productivity out of Congress, out of the state legislatures, and that leads to cynicism in the American people. I think we can start to save our democracy, as we envision it, if we are successful with the Census in 2020 and the redistricting in 2021. And, again, what I really want to emphasize is that I’m looking for a fair effort, not a partisan one. Not one that favors Democrats. I actually think that we should make this a battle of ideas between conservatives and progressives, and not make it a function of who is best at drawing the lines, or who can best figure out how to rig the Census.

Can you talk a little about who’s funding the NDRC, and to the whom the PAC is disbursing money?

The NDRC actually has a 527, which is a PAC that supports candidates directly. We also have a 501(c)(3) that essentially funds our litigation. The Census litigation that we have brought has been done, I’m very proud to say, by my law firm, on a pro-bono basis. But other lawsuits that we have filed — for instance in Alabama, Georgia, and Louisiana, where we are alleging racial gerrymandering — those are being paid for out of that 501(c)(3). And our advocacy efforts come out of our 501(c)(4) account. So, there are those three accounts. We have raised about $32 million since we started in January of 2017.

You came to this issue in a public way after your time as AG was done, but you’ve spent many, many years working in the Justice Department and in government with some proximity to questions and discussions of voter enfranchisement and gerrymandering. I’m curious, why wasn’t this acted on sooner, based on what you saw? And why did it not seem to be as important of a political priority until, you know, the last decade or so?

That’s a good question. You have to look at what happened in 2011 after what President Obama described as the “shellacking” that occurred in the midterm election in 2010. Princeton has looked at what the Republicans did in 2011 and said that it was the worst example, in its totality, of gerrymandering in the last half-century. People ask, “Well, why’d you get involved then?” Because what happened in 2011 was kind of off the charts in terms of the gerrymandering. And then you saw the impact of it over the course of this decade. Once districts are put in place, it’s very difficult to try to dislodge them because our system’s designed so we do this only every ten years. We’ve filed lawsuits now to stop Republicans in Georgia, for instance, who tried to redistrict mid-cycle, which is kind of breathtaking. To the extent that there were ways under the Voting Rights Act that you could get at racial gerrymandering, we certainly brought those lawsuits. But when it comes to partisan gerrymandering, I don’t think that people were focused on that issue because it happened in 2011, and people didn’t really start to see the impact of it until later, a couple years or so after that, when you see laws being passed that were inconsistent with the wishes of the people. Or where people wanted legislation and saw that it didn’t happen. For instance, with gun-safety measures. Like, 70, I dunno, 80 percent of American people want to have expanded background checks, and yet that doesn’t happen at the state level, or at the federal level, because of people in safe districts. And the people in those safe districts are in the pocket of the gun lobby. This really bad gerrymandering only happens in 2011, and then you don’t see the impact of it for a couple of years. In 2013, 2014, people start to realize that this is a problem, and that’s when I’m transitioning out of the Justice Department and why I decide to make that a focus of my post-government work.

Got it.

But that Princeton study is really important. Again, this isn’t something that I’m saying. This is kind of a nonpartisan, wonky thing done by my archenemy, because I went to Columbia, but the Princeton folks said that 2011 gerrymandering was the worst in the last 50 years.

I want to move to your work for Uber and Airbnb …

So, we’ve gone through all the sexy stuff now …

Now for the boring shit. Uber and Airbnb. You left the Department of Justice in 2015, and when you went back to Covington & Burling, I think it was only a couple of years later that you began doing this work for both companies as part of the firm. At Airbnb, you were addressing issues of discrimination on the platform, and at Uber, it was an internal corporate culture crisis. So, they are distinct but related. How were you drawn into the work? What was the process there?

Typically, clients or companies, individuals within companies, have issues that they have to deal with, and they then try to determine who’s a good lawyer who could help us with this, what’s a good law firm that could help us with this. So we got calls from Uber, from Airbnb in ways that we frequently get calls from clients who have issues that they need to resolve.

Were these companies clients of Covington & Burling prior to your hiring, or did they seek you out?

I think the answer to that question is both: Yes, they were clients before, and, yes, they sought me out.

When these companies hired you, were you concerned that this would be viewed as a savvy PR move of some sort — a way for them to sort of launder the controversy?

No. I’d say two things about that. One, that was not how they approached us or me. They were sincere in their desire to work through the issues that they had to confront. That’s one. And two, I wasn’t born yesterday. I would not allow myself or my firm to be used in that way. If I thought that a client simply wanted to use my name to try to somehow get beyond a legitimate issue that they had without actually dealing with the issue, that’s not a representation that I would take. With regards to Uber and Airbnb, they were, I thought — and I think it’s proven to be true — sincere in their desires to really try to work through those issues. There were some questions raised at the beginning, concerns raised by some of the early investors at Uber, about whether or not, given the fact that I had done work and the firm had done work for Uber before, we could be as independent as was needed to do the assessment that was being asked for. And I remember telling the appropriate people at Uber that I wasn’t going to do anything, the firm wasn’t going to do anything, other than an independent assessment to lay out the facts as we found them, and that that potentially could be the last thing that we would do for Uber if people were not happy with whatever it is that we found. But I assured those early investors that we would do a complete and thorough job. I think everybody’s been satisfied that that is in fact what we did.

Looking back on your work for both companies, you’ve produced big reports with lots of individual recommendations for fixing issues. Based on your knowledge of what these companies have done since then, do you feel that Uber and Airbnb have adequately addressed the concerns or implemented recommendations that you made?

Yeah, I think they actually have. Again, I’m just talking about publicly reported stuff; I’m not sharing anything that’s attorney-client privilege. I know the board at Uber unanimously accepted all of the recommendations that we made. And I know that since then, they have been very serious about making real those recommendations that we made. The new general counsel there, Tony West, whom I worked with at the Justice Department, and Dara [Khosrowshahi], the new CEO, whom I’ve met with and talked to, are quite serious about making sure that the recommendations that we made are put into place, and then going beyond those recommendations. I think the same is true with Airbnb. Airbnb did not react defensively to those racial concerns. What they asked was, “Make an assessment: Do we, in fact, have a problem?” Then they put in place measures to try to deal with the problem, to try to eliminate it to the extent that that was possible, and to make clear that hosts who acted in a way that’s inconsistent with Airbnb policy would be thrown off the platform. Those kinds of things, I think, are indications, both of Uber and Airbnb, that they are taking the necessary steps. It won’t mean that it happens overnight, but it means that they’re on a good path to get to the place where both companies want to be.

There’s a recent report in Variety that you and colleagues at Covington & Burling pitched Hollywood executives on this kind of work, and illustrated that what you did for Airbnb and Uber, you can do for them. Has anybody bit on that offer that you can talk about? And secondly, what are the things that you did for Airbnb and Uber that you would be able to do for studios or other companies in Hollywood?

Well, what I’d say is yes, we’ve done some work for entertainment companies, and no, I can’t talk about who they are. We’ve done things for other companies as well, again, things that have not necessarily been public. I think we have to understand that we’re at an interesting time in our nation’s history. The consciousness of the nation has been raised with regard to gender-discrimination issues, racial-discrimination issues in the private sector, the way in which women are treated in terms of advancement within companies in the private sector. These are issues that I think companies are grappling with beyond the tech sector, and beyond the entertainment industry. We have been interacting with companies outside of those two sectors, well-intentioned companies with good management and with involved boards of directors, who are asking themselves the question, “Where do we stand with regard to these issues?” That’s how we have become involved. Companies will say, “We think we’re doing pretty well, but we’re not totally sure, and we’d like to have an independent set of eyes look at how we’re conducting ourselves, and make recommendations about where we’re not doing as well as we should.” Or tell us, “Our sense that we’re doing pretty well is actually borne out by the facts.” I think that being proactive in this regard is the best way to deal with these issues, as opposed to waiting for something to come out in Recode or The Wall Street Journal or a lawsuit. To be proactive, to get ahead of these issues — because I think it makes both business sense and there’s also almost a moral component to it as well.

As the AG, you were directly responsible for prosecutors who were in control of enforcement in the corporate arena for a lot of these companies. There are still lots of ongoing investigations elsewhere, at the state level and federally. It’s not the DOJ’s purview, but I know Uber has, for example, an ongoing EEOC investigation. I’m curious about how you would address your work for these companies, if you were to return to a position in which you’d be responsible for enforcement. Is it a conflict of interest?

It would be the same kind of things that [happened] when I went back to the Justice Department after I left Covington the last time — when did I start? 2008, 2009? — when I went back to the department back in 2009. There are some pretty bright lines there. I could not deal with any matters that I dealt with in private practice. I did not really deal with matters where Covington represented a client. There’s some pretty bright-line ethical restrictions on what any lawyer going back into government can and cannot do.

Have you ever read, or heard, about the book The Chickenshit Club by Jesse Eisinger?

No, I don’t know that one. That’s an interesting title.

You’re not familiar with it?

No, I’m not.

Jesse is a reporter for ProPublica, and his book came out recently. The thrust of his book was that there was a culture shift — and he’s one of a number of critics who posed this — that the Justice Department, and the enforcers in general, like at the SEC, got soft on white-collar crime. I bring him up because critics argue that the political climate today stems from the fact that there was a lack of accountability in the last decade, particularly after the financial crisis. You’ve said in the past that had people committed crimes you would have gone after them. I know that you talked about the hazard of prosecuting companies because they’re too big, and at least going after them and taking them to trial could have posed greater structural damage. I’m curious if your thinking has evolved on that at all, or if you still stand by those remarks and observations.

It’s interesting. I think that the relationship between the prosecutors at the Justice Department and regulatory authorities — I mean not only here in the United States, but overseas as well — which was of concern in the early parts of the Obama administration, has really really gotten better. There is much better communication. So the ability to prosecute, to bring charges, and to have appropriate collateral impacts, as opposed to unintended collateral impacts — you have much more control over that than you did at the beginning of the Obama years. And that was a function of our reaching out to the regulatory authorities here in the United States, but I would emphasize to the regulatory authorities in other parts of the world as well, chiefly the U.K. and the E.U. We’re at a fundamentally different position, well, we were in a fundamentally different position toward the end of the Obama administration, toward the middle of the Obama administration, than we were, say, at the beginning of it.

Regardless of whether or not you were in dialogue with regulators on these points, there was still a sense that after, say, Arthur Andersen, the climate for white-collar prosecution and the tenacity with which prosecutors took companies to trial were diminished. That’s the thesis of a number of critics who say it’s evidenced by the decline in these kinds of trials and that the apotheosis of this was the failure to prosecute anybody in the financial crisis. Do you think that that narrative holds any water? What accounts for the changes in tactics, or in thinking, about how prosecutors would go after companies, and what they would try and win over the course of the late ’90s into the 2000s?

I actually have in front of me something that happens to deal with statistics, as opposed to feelings that people have, that shows that the Justice Department, while I was there, and probably now as well, has been appropriately aggressive when it came to bringing these cases. There is this feeling, I understand that, that people were not held accountable for the financial meltdown. What I would say to that is that we made serious efforts at holding companies accountable. I think what people tend to not view appropriately is that there were record-setting amounts of money that were extracted from banks, and then distributed to people who suffered as a result of some of these bank practices —

I’m sorry to interrupt. I have the numbers in front of me: 49 financial institutions paid around $190 billion in fines to federal and state governments and agencies between ’09 and 2015. And that’s from Keefe, Bruyette & Woods. What people criticize is that these fines allowed individuals to escape accountability. Do you think that there are people whom you were unable to hold accountable who did wrong during the financial crisis?

No, I mean, what I’d say is that we tried to build cases against companies and against individuals to hold them accountable. It wasn’t for lack of trying. You have to understand that bringing a case against a high-ranking head of some financial institution — those are the kinds of cases that people go in to government to make. You’re in the Southern District in New York or the criminal division here in Washington, D.C. So, those efforts were certainly made. There are standards that the Justice Department has to meet before it can bring a case, and that is that it’s more likely to win the case than not. And applying those standards, looking at the facts, looking at the law, looking at the ways in which these decisions were structured within these companies, appropriate decisions were made about the bringing of cases. And it’s not true that no cases were brought against individuals. I have stuff I’m looking at now, as I said, that has a whole range of people where cases were brought and even actually where companies were charged. I think that this is something I’m not sure is factually correct, and beyond that, the thing that gets me is that it calls into question the motives of the people I worked with, the integrity of the people I worked with. In essence, when I hear that, I say, “So, what are you saying here? That we didn’t bring cases that we could have brought? And if that were the case, why didn’t we bring them?” When you ask those questions, I think that is in some ways the ultimate pushback because the people I worked with were honorable, were aggressive, and wanted to hold companies and individuals accountable.

I’m thinking about cases brought against Enron or Arthur Andersen that resulted in the destruction of those companies — you didn’t see that with any of the major banks in the financial crisis. Without calling into question anybody’s integrity, why didn’t that happen? Is it simply that there wasn’t enough material to bring to a case? Was it that there was a change of approach needed to deal with firms that had done this? You had deferred prosecution agreements and other ways in which the DOJ talked about holding people accountable, like extracting really large fines and damages. Did levying those fines hold companies accountable as effectively as going after a company and prosecuting individual executives?

Well, I mean, if you look at Enron or WorldCom, for instance, those involved accounting fraud with improper manipulation of the books and records of those companies at the highest levels. I mean, senior executives were the primary actors there. In the financial crisis, these mortgage activities were in one business among many, and there was not the same evidence of involvement of senior executives, and you weren’t necessarily able to come up with the quantum of proof to show that they were personally — again, talking at the most senior level — personally involved in misconduct. I mean, it also — in Enron and in [WorldCom], just picking those two because they’re the ones I have most familiarity with, they had insider witnesses who could provide a road map of criminal conduct. Despite a lot of investigation, you didn’t have the same kinds of witnesses when it came to the financial-crisis investigation. There’s a speech that I gave at NYU in 2014 toward the end of my time at DOJ talking about financial fraud, about what it is we did, and also about some changes that I thought were appropriate that we needed to put in place so that the Justice Department and other regulators could act more effectively.

One specific criticism that’s been raised is over the rise in deferred prosecution agreements, in which companies don’t necessarily admit liability. In 2015, which was your last year, there were, and I think this is the record, 102 non-prosecution and deferred prosecution agreements. Do you think that deferred prosecution agreements were an adequate way of addressing white-collar crime? What do you think pursuing those kinds of agreements and those sorts of negotiations was able to achieve for the Justice Department or on behalf of the government that another strategy might not have?

I think deferred prosecution agreements can be appropriately used, yes. I do them on a case-by case-basis. Certainly, you have to go after individuals, and hold individuals accountable, that’s kind of a bedrock principle, but then when you’re talking about a company, you also have to understand that when you bring a case, a criminal case, a company’s criminally charged; you have the potential to punish innocent people within the company as well. Let’s say there are, I don’t know, bad executives who’ve done inappropriate things. Well, there are shareholders who can be impacted by a decision the government makes, there are other employees who might number in the thousands who could be impacted by a decision that the government makes. Again — doesn’t mean that you’re not taking action. Deferred prosecution agreement typically involves monitoring the activity of the company, having some degree of assurance that the company won’t repeat, that the company’s conduct will change. Usually, there’s the payment of a fine, so that there is accountability, and then a monitoring regime put in place. So I think if you look back at the Arthur Andersen resolution, clearly something needed to happen to Arthur Andersen, but did everyone who worked at Arthur Andersen need to lose their jobs because of what some people did at that company? And, again, that doesn’t mean that you aren’t aggressive or that you don’t hold companies accountable. But you really do have to take into consideration what are the collateral impacts when the Justice Department wields its enormous power, and I think that the Justice Department can appropriately take into consideration what those collateral impacts are.

When you’re examining the specific record, I think the biggest example that people raise is with HSBC, which reporting suggests is a company that had laundered hundreds of millions of dollars in drug money and got away with a fine. There was no extended prosecution, and reporting suggests that this was a case of quote “too big to jail”? Do you think that “too big to jail” is sustainable and sort of an acceptable idea for white-collar criminal enforcers, looking into future?

No, and I never said a company was too big to jail, too big to hold accountable. What I was trying to say, I guess, in doing that — it was at a hearing I think I had or something, I don’t remember — was that, again, you can take into consideration the collateral impact of a resolution — What is this going to mean? — and people have to remember when we’re talking about some of these cases, and I don’t want to talk about that one specifically, let’s just say the resolutions of some of these cases occurred while we were still dealing with the aftereffects of the great recession and our financial system was still not fully functioning. So there are things that I just don’t have the ability to talk about with regard to the HSBC determination, but what I can say is that since those early days, the conversation between regulators and prosecutors, the relationship between regulators and prosecutors, is really much better and gives prosecutors more latitude than perhaps people at the Justice Department had at the beginning of the Obama administration.

Broadening the conversation a little bit, a number of your former DOJ colleagues and folks in government have moved to the private sector, and this is sort of a long-standing practice. Lanny Breuer works with you at Covington & Burling, and Mary Jo White was at Debevoise & Plimpton both before and after her time at the SEC. This, I think, could be pretty accurately described as a revolving door. Do you think that this sort of easy transition between the defense bar and big law firms and regulatory or enforcement agencies poses a conflict of interest or could have any repercussions on the quality and rigor of the enforcement administered?

No. I think the question is, you know, how did Mary Jo White conduct herself as the head of the SEC? How did Eric Holder conduct himself as the head of the Justice Department? And I’ll put my record up against any Attorney General before me or after me with regard to how aggressive my Justice Department was with regard to regulating any sector of this economy: financial sector, tech sector, you pick whatever sector you want in our society, and I would say that the Justice Department that I led did things in ways that were appropriate, and we were, as I said, aggressive. So it was unaffected by the work I had done, by the employment that I had before, and the same would be true now if I went back into government. Whatever position I had, I would focus on the responsibilities of that position and do what I was expected to do in that position, irrespective of what I had done before. I mean, this is something that lawyers do. I’m a person opposed to the death penalty, and yet, as Attorney General of the United States, I had to make determinations and apply the law in making death decisions. I authorized the death penalty, for instance, with regard to the Boston Marathon bombings. People need to understand how good lawyers have that capacity. You know, when I was Attorney General of the United States, my client was the people of this country, and I represented the people damn well. Now, I’m here in private practice and my responsibility is to a different set of clients. I will say that in my work here, I still am doing things that have a positive impact for the people of the United States —

You could also say, though, a lot of people would have discomfort with a guy who’s an oil exec — I mean, I think we can look at the Trump administration for some of these examples. Somebody who worked in the oil industry and then goes to work at the EPA and then goes back to the oil industry. I think people would kind of clearly draw a conclusion like, “Oh, he’s going to bring an attitude sympathetic to the needs and wants of the industry in which he worked before he was in office.” You’re saying, as I understand it, that lawyers just have to represent who their clients are and that’s the interest they bring to the job. Do you think —

These have to be individualized determinations. It’s one thing if you’re a lobbyist for, I don’t know, the energy industry or something like that, and then you become the head of the EPA — that, okay, I wonder about that. And if you were a lawyer who only worked in one field, and then you were expected to go into a regulatory position over that field … Now, that doesn’t mean that person can’t do the job effectively, but I think in the confirmation process, those are the kinds of questions that have to be asked. Are you going to be able to put aside that which you’ve done for the last 20, 30 years, and somehow now regulate the industry that you have worked with or defended? Those are legitimate questions, and I’m just saying that with regards to my Justice Department, my time as Attorney General, and the people who worked with me, I’m comfortable with the way in which we conducted ourselves.

Just to close this out: There’s been a lot of talk about you throwing your hat in the ring — I don’t know, you can choose your metaphors — for 2020, and you said on Colbert earlier this summer that you’d make a determination early next year, if I remember correctly. Has anything changed, are you still considering, thinking about it?

Yeah. Nothing’s changed in terms of the timing, but I gotta say that between now, I haven’t really thought about it an awful lot. My focus at this point is on the midterms, gerrymandering. We’ve fought lawsuits, and we’ve done all of the things I talked about — now, the electoral part of what we do is the thing that I’m singularly focused on between now and November 6.

And outside of 2020, one of the main lessons that a lot of people drew from the 2016 election — and I think this is probably true of any Democrat with a national political profile more broadly, regardless of what they’re running for — is that Hillary Clinton had these sort of extensive ties to the private sector. She took money for speeches with big banks and was trying to run as somebody who could champion reining in those banks and the excesses of the financial sector. I’m curious: How do you think about, for whatever you choose to do in the future, how you would talk about what you did for Covington & Burling and the degree to which you’ve worked for folks who you may soon have to regulate? I know we touched on this earlier, but I’m kind of more interested in thinking about it broadly and how you think of it affecting your work going forward in any capacity.

Well, actually, I’ll speak personally here. I mean, there’s nothing that I have done at this firm, there’s nothing that this firm itself has done, that would make me feel uncomfortable in going back into government at whatever level, at whatever job, and doing the job in an appropriate way, in an aggressive way. I think my record would show that I was at Covington for, I guess, eight years or so before I became Attorney General, and if you want to know what kind of government official I would be in the future, you only have to look at the past, and you could see the way in which I conducted myself as AG, having left this firm before, and as I said, I’m comfortable with the record that I had as Attorney General.