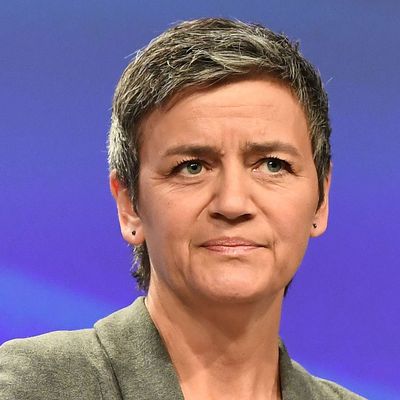

There’s only one government official around the world who really keeps tech executives up at night: Margrethe Vestager, the European Union’s top antitrust official. A Danish politician who became the Commissioner for Competition in 2014, Vestager has since launched investigations and levied hefty fines on tech heavyweights like Apple, Facebook, and Google.

Some of her greatest hits include a $15 billion penalty on Apple for its long-standing tax scheme with the government of Ireland, which allowed the company to pay a corporate tax rate of one percent; a $5 billion fine of Google for exploiting its search monopoly; and a $122 million punishment for Facebook after finding that the social-media giant misrepresented how it would treat the data of WhatsApp users after acquiring the messaging service in 2014. Vestager’s aggressiveness extends beyond tech as well; she’s recently launched a major collusion investigation into Germany’s biggest carmakers.

The commissioner recently sat down with New York for a conversation while on a visit to the United States, during which she met with American regulators and spoke at several conferences. Over the course of our conversation, Vestager discussed the culture of Silicon Valley’s executive class, a potential inquiry into Amazon, why European regulators are paying close attention to tech mergers, and more.

So I just want to ask, what are you doing in the U.S.?

Well, we came here for the Georgetown University Faculty of Law conference. They have this once a year. Basically, there are two must-go conferences, so I do one one year and one the other and sort of alternate. Because it is a very good place to say what is the state of play and how do we see things in Europe. The second thing was to do what we call a bilateral with my U.S. counterparts — Makan Delrahim at the DOJ and Joe Simons of the FTC — to reinforce our already good cooperation.

What is the state of play?

Well, it is a big question. The state of play is that we are quite busy with tech cases and other cases. The market is changing quite a lot, and we talk a lot about our antitrust cases, but people shouldn’t underestimate what is going on when it comes to mergers and acquisitions. I think this year will be our second all-time high. This is not only with tech. This is all industries. We are dealing in beer, cement, trains, signaling, steel; you name it, we got it.

Europe seems to have been so much more proactive on this front than the U.S. has. How would you characterize what Europe is doing as distinct from the U.S.?

First of all, I think there is a difference in European culture when it comes to the willingness actually to frame the marketplace. Back in the days when Europe was completely destroyed, our founders saw the need for the market to play a constructive role because it has played a negative role in the running up to the Second World War. So there is this European culture to say, well, we are actually willing, in our democracies, to make decisions to regulate the marketplace, and then, within this regulatory framework, say, “Go compete.” And then, again, when you do compete, you have to do that on a level playing field, which is why we have competition laws as well.

Has the U.S. adequately prosecuted, regulated, or enforced rules of fair competition, in your view?

Well, it is very difficult for me to say because this is none of my business basically. And our work is very specific. For instance, our Google cases. They come from looking into the market complaints coming from the U.S., from Europe, saying the Google behavior in the European market is not how it should be, and from that comes our cases. I know what we do, but I don’t second-guess why my colleagues are doing things or not doing things.

The reason I ask is that it strikes me that these are global businesses presenting global issues, but you can only tend to the European market. So how do you develop responses at the appropriate scale?

Well, you are obviously right to say that we have global businesses, but we do not have global law enforcement. We also don’t have global legislative framework here. But what we have been doing over the last decade and a half, two decades, is to build up an international competition network. In the beginning, only 14 jurisdictions, and now more than 130. It is low on protocol and high on substance. What we have seen sort of recently is that there is a lot of interest from sister jurisdictions to learn why is it that you are doing what we are doing. Can we take an inspiration from you? Maybe we are going to consider some of the same issues. I think maybe that is not a perfect response because we don’t have global law enforcement, but at least it is second best because it allows people to come together.

Do you get the sense that the U.S. takes lessons from what the European Commission has been doing in Europe?

Well, that I wouldn’t know fully, but I sense that the debate in the U.S. has changed over the last couple of years.

There’s been talk among Republicans about going after big tech companies over what they claim is ideological bias. Do you view that as an issue or something that you are reckoning with?

No, we don’t see that. Of course, every company has a culture, but what we see most is that when we have a case, it is more because you want more of the market. You want to make a better business; you want to make higher profits. So maybe it is about something that is even more fundamental than opinions; it is about fundamentals in human nature. It is about greed.

What is your ideal approach to pursue mergers and acquisitions? Are you going to block more of them? Tech in particular is such an acquisitive space, and you see more of these kinds of deals happening. In the U.S., it has been very hands-off.

Well, when a merger is notified to us, we see what is the market we are dealing in. Then we try to figure out: Can the consumers turn to someone else if prices go up? If choice goes down? If they close down innovation or put products away and don’t market them anymore? This is our test of consumer harm, that prices go up, choice goes down, innovation doesn’t happen. Now, we have made it routine to look into questions of data, what happens with data in a merger. Will this merger mean, then, that no one else can get access to this data? That merged set of data then becomes this very crucial source for innovation that will enable you to a complete different degree. Will this give you such high barriers of entry that one else can come there? Not because of more old-school issues, like very technically intensive or capital intensive issues, that will also make very high barriers of entry, but also data presenting a very high barrier to entry. So that we also get a full understanding of that. We do not make sort of a choice saying that now we will prohibit more. We will prohibit if it turns out that something that will harm the consumer cannot be fixed.

Do you think too many acquisitions that involve the consolidation of user data have taken place?

I cannot answer that as a general question.

To shift to some more specific companies, did you happen to see the interview in Forbes with one of the co-founders of WhatsApp?

I have not seen it. I only heard about it.

In the interview, Brian Acton says that he was coached by Facebook executives to effectively lie to investigators — to say that there would be no data-sharing between WhatsApp and Facebook, when in fact the company had already been laying the groundwork for that to happen. This isn’t quite new, you’ve already fined the company, but I am curious the degree to which you think that Facebook has a culture, or a proclivity to, misrepresent what it does with user data?

I think it is difficult to say. In this exact case, what we were told is that the data set would not be put together. Then, of course, after a very short period of time, it was done anyway, so we realized something is wrong here, that we were not told the full truth. And in this case what Facebook admits to, the wording is something like, at least …

Negligent?

Yes, exactly. And for this we fined them 110 million euros because this was a very, very severe violation. The luckiest thing for Facebook was that we actually did the analysis anyway. Even though we were told this would not happen, we set up the hypothesis, What if it happens anyway? Will it then be damaging for consumers? And we found that not to be the case. When I say it was lucky for Facebook, if it had been the case that was damaging for consumers then the entire merger would be at risk.

In the U.S., at least, there’s always been an argument that, well, because services like Facebook and WhatsApp are free, there’s no real problem. The idea is that it’s not an antitrust problem because the consumer benefits — it’s not like prices are being gouged. Is consumer benefit the guiding idea of how you approach what you do?

First of all, and that for me is very important, we don’t consider these services to be free. We think it is very important to break the illusion that it is for free because you do pay. You create value when you do a search because you create data. Very often, people pay quite a lot with their data for the services that they get. We still have not developed in a way that will allow you to take the data created and also give access to that to a third party. So, now we say you own your data, but at the same time, very often, you have to hand over a license to use that for free. And we still cannot enable people to say, “Okay these are my data. Over, maybe, a week, I have created this amount of data. I will give access to someone else — maybe for payment, maybe not for payment. But I will enable more competition in the marketplace because I will allow more people to have access to an enormous amount of data around what I am doing.” This is important because payment can come in so many different forms, and payment with your data is just the latest addition to that.

When we look at consumer harm, we don’t look at issues of labor because mergers or not mergers, labor laws will have to be upheld. Obviously, that is important for us, that you have a good working environment. But we have a broad concept of what is consumer benefit and affordable prices — obviously, that is a very important thing because a lot of people do not have enormous budgets. For them, low prices mean something. It is better to pay five euros than seven if you don’t have that much money. But second, you will want to have choice because if the thing only comes in black, that doesn’t give much color, so you want choice as well. But the third thing is, you also want innovation. You want companies to be pushed to create not only new stuff but new series, new ways of organizing things. So it is a need of a broad way of looking at what is the preferred sort of consumer benefit.

Do you think Silicon Valley companies recognize these goals and respect them?

We have found sort of the opposite in the Google Android case. Because this is a case with Google being dominant in search to Android, saying to a phone-maker, if you want to carry Play Store — which producers of phones considers a must-have app because this is where you get your games and your weather apps and whatever — then you have to take search and Chrome as well. So you tie the product together. Not only do you do that, you also put up an exclusivity payment. So you’re preinstalled, but you also have that you are exclusively preinstalled, and last but not least, if a phone manufacturer said, “Oh, but I will open a new line of Android phones. Someone else will put a new version of Android and a new search app and a new browser,” they say, “Well, then you are out of the Google suite completely.” That is exactly to say, well, then no one will innovate on the Android source code because you cannot find a phone manufacturer who will ever be able to carry your innovation.

You have announced fines and multiple investigations of Alphabet and its various businesses. Are they learning their lessons?

Well, that still remains to be seen. The latest decision — they will have to live up to that I think in a couple of weeks, something like that.

Which case?

The Android case.

The Android case.

Yes, because we have the decision, you have to pay the fine, you also have to live up to the decision, which basically says you have to live up to this behavior.

What has their history of compliance been like so far?

Well, it is very difficult to talk about a history of compliance. No matter if you appeal the decision or not, you will still have to live up to the decision, no matter if you go to court or if you don’t.

And when it comes to the political pressure these companies have tried to mount … in the U.S. it is formidable. Do you feel, or have you ever encountered any of that pressure in Europe?

Well, where we see it, we also see that the amounts of money spent on lobbying is increasing. There is a much stronger presence now of lobbying tech companies in Brussels compared to previously. But I think that there is a pragmatic critical stance to lobbying because there is a different approach and a different history.

In Europe and the U.S. right now, there is an enormous amount of concern about the way these companies have so much data, and so much market power, and can be exploited for international political-influence operations funded by governments or individuals. Do you feel that any of that falls into you purview?

Not from a competition point of view, but my colleagues are looking into that. For instance, the Facebook and Cambridge Analytica scandal is being investigated both from a fraud point of view, violation of privacy point of view, violation electoral loss perspective, so it is the thing that a lot of people take an interest in.

What is the thing that you have most learned about these companies and the way that they operate?

That speed is of the essence. We do what we can to speed up the work that we do — we use more digital tools in the way that we work, but our basic principles remain vibrant and relevant.

And of the companies themselves and the way that they operate? What has struck you the most about how they approach and act and conduct business as it relates to competition?

I think that, as previous giants did, they seem to think that these are the way that things are going to remain. But those who were the giants ten years ago, they are not here anymore — at least not as giants. Those who were the giants 20 years ago, they are definitely not here anymore as giants. I think that is a lesson for anyone: If you think things are going to remain the way they are, you are wrong. Here we have not even seen the beginning of quantum computing and blockchain. When you have that full rollout, things may very well change.

Assuming that you have been in touch directly with the leaders of these companies, what can you say about your impression of how seriously they are taking this, and if they understand what you just said?

Actually, I wouldn’t know. Not because I don’t investigate their motives. I can only see in changes of behavior. That is, I think in some of these areas it is coming, and in some of these areas it remains to be seen. We haven’t even passed the deadline of compliance with the Android decision yet, so we still need to see how they will put that into effect.

To go to a separate decision or action of yours — or to the E.U. rather, with Apple and tax. That action didn’t come out of nowhere. People have been talking about those issues for a really long time. What do you think accounts for the shift in energy in Europe in going after American companies?

Well, it is not about American companies, it is about secrets being unveiled. It was never a secret that you cannot hand out a government subsidy not being available to other companies. We have a ban of these sort of selective advantages. That has never been a secret. You cannot do that in terms of a building lot, or a very cheap loan, or a tax benefit, for that matter. Everyone knew. What was a secret was the companies that benefited from that happening anyway, and the Apple case actually started from questions being asked in the U.S. Senate about how Apple was organized. That was the starting point of the Apple case, that ended up with Apple having to pay unpaid taxes of 13 billion euros. That was appealed, but now the unpaid taxes have been paid — it is in a closed account, and it will stay there until the courts have done their rulings. But I think it is important that now we know so much more, and we can actually make change happen. Because most people pay their taxes — most businesses, they do pay their taxes, and they contribute to the society where they do their business. It should not be most companies; it should be all companies.

The news that you are looking at Amazon made people very curious. What can people expect from that?

Well, the thing is, I don’t even know that yet. Next steps will be built on the facts of the case, and we need to establish what is actually going on before we can make any decision if we will officially open a case or not. I think it is still important that when we open a case, when we do something, it is the facts of the case, it is the evidence we hold, it is the court practices that will inform our decision-making. Because we cannot possibly live up to expectations of one or another or a third party, because they are created from another starting point. We live in union built on the rule of law, so obviously this is our obligation.

These companies are so powerful, and your cases in Europe are the first time that many of them are being called to account, at least at this scale. Have you encountered any brushback? Anything that has offended you or caught your attention in such a way?

Well, first, the thing that strikes me the most is that we talk about them as if they are the same, but they are very different. They have a very different business culture.

How are they different?

Well, Amazon is not the same as Google. They have a different business culture; they come from a different starting point. Facebook as well. Yes, they are all big tech companies; yes, they all hold enormous market shares, but they are still different.

And how does that difference play out in the way you approach them?

Well, it does not change the way that we approach them because we only approach them if we have a concern, if something is going on that shouldn’t be going on. But, no, they just are not the same.

Well, how do you think those differences play out in what they do, besides that they offer different services?

Well, I don’t know because also when I see CEOs of a cement company or steel production or whatever, it is not that they are … there is another thing that is playing out here, which is if you can sense if they come in to just consolidate or to just challenge, if they come with a competitive culture. That is more how I sense the differences than in other categories. You get my drift?

In the U.S., one defense of Facebook executives is the idea that they were caught by surprise by the far-reaching effects of growth. Do you think that tech executives are sufficiently awake to those consequences of their actions now?

I wouldn’t possibly know. Of course, it’s an important thing to be able to put yourself in someone else’s shoes, I’ll say that. If it were my company, and I saw that it had been used to do something as fundamental as influence democratic elections, that would be devastating.

Do you think European governments are taking seriously both the challenges posed by the competitive actions or anti-competitive actions of these companies, as well as the scope of their impact?

Yes, I think they do. I think they do. The thing is, of course, that we’re very careful — goes for my colleagues as well — as to how to translate that into action. Because you want to regulate, but you don’t want to overregulate. To give you one example of that: A colleague of mine has tabled the proposal — I think it’s a very good idea — to make more transparency in the business-to-platform relationship because that comes back over and over and over again. Because the business will say, “Oh, had this been the physical world, it’d be the equivalent of someone painting our windows, blocking our door, taking down our sign. We couldn’t be found anymore. We were basically closed down, but we have no idea why it happened or what we can do to correct this.” Apart from that, we get a lot of different feedback. Instead of just saying, “Oh, we take that feedback and we make new regulation,” we create an observatory. So that in a much more sort of vigilant way, we can observe what is going on in order to be able to take action, but making sure that you do that in a way that is proportional to the issues that you want to regulate, instead of overregulating things.

To what extent are you thinking about the fact that the rest of the world is watching and looking to Europe to figure out, What do we do about this?

Of course, it’s an enormous privilege and an honor if you can inspire other people, but still for us, the most important thing is that when we have a case, that it will have a very strong case for it so that it will stand up in court, because we have to be proven in court. We can make a decision, but then that can be appealed, and, of course, we want our decision to be upheld. So, the quality of our case, the dates, the evidence, the case log, that has to be impeccable, and that, I think, is the main … what was the new word here … lodestar for us. And then, of course, if we can inspire that would be great, but we have to do the cases where the cases are.