Last January, before Beto O’Rourke’s campaign raised — and ultimately dashed — the hopes of Democrats around the nation, I flew down to Dallas to see him. We had first met some years before, back when he was a city councilman in El Paso, but he had become more important since then, as a young Democratic congressman with a safe seat in the House. For some reason, though, he had decided to risk his career on a high-stakes gamble, running against Senator Ted Cruz. From afar, it looked like a mismatch. Cruz was one of the country’s most high-profile conservatives, in a Republican state, and O’Rourke was still largely unknown across the vast expanse of Texas. El Paso is as far from Dallas as New York is from Detroit.

That Friday, O’Rourke was committed to appear at a series of events organized by a volunteer group called DFW for Beto, which had spontaneously come together on Facebook. O’Rourke spoke at an organizational meeting held at the home of one of DFW for Beto’s founders, and then drove on to a town hall event in the working-class suburb of Garland. Chris Evans, O’Rourke’s spokesperson and constant travel companion, told me he had been surprised to see around a thousand people had RSVP’d for the town hall on Facebook. He and O’Rourke wondered aloud about what percentage would actually show up on a weekend night, ten months before the election. Maybe they’d get a few hundred?

O’Rourke’s wife, Amy, drove a rented SUV to the union hall where the event was to be held, navigating with her phone. O’Rourke asked her to pull over at a gas station, and we went in to grab some coffee. He had been campaigning since morning. “You know what, the day really knocked the shit out of me,” O’Rourke said as he filled up a large foam cup. Darting over to the snack aisles, he grabbed a bag of chocolate-chip cookies and a Snickers bar. “I’m a little anxious going to this town hall,” he said. There could be a decent crowd. “I want to deliver, and I guess it’s a good energy, but it stresses me a little bit.”

A woman who was at the counter paying for gas gave us a searching look.

“Is that you, Beto?” she asked, pronouncing his name Beeee-to.

The woman said her own name was Joni Evans, and she told O’Rourke she was a fan, and had been following him online. “I hope you beat Ted Cruz,” she said. “I’ll be trying to help you out.” She took a selfie with him, and then she walked back out through the sliding doors, slipping her phone into the bedazzled back pocket of her jeans.

O’Rourke had never run a campaign outside of his hometown before, and at the time, such encounters were still a little weird for him. “Still, even doing it right now, it feels unreal to me,” he said a few minutes later, as we stood next to the SUV outside the union hall. He was experimenting with an unusual strategy, livestreaming many of his daily activities, but he didn’t yet know if it was working. He was ushered into a holding room, where Evans filmed him making a last minute appeal for Facebook. “Come join us,” he said, “there’s still time.” We could hear a strengthening roar filtering through the walls.

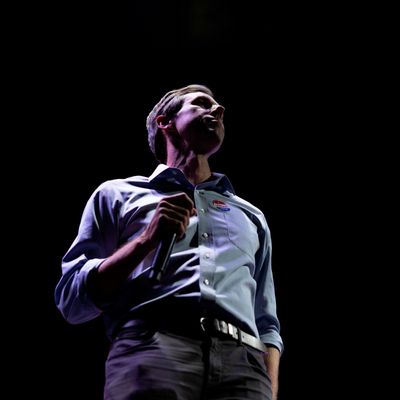

The number of RSVPs proved to be way off. There weren’t 1,000 people. The crowd numbered more than 2,000. Recently, Evans told me that was a turning point for the campaign staff — the moment they realized O’Rourke was beginning to break through. The crowd chanted “Beto! Beto!” as O’Rourke waded forward. “This feels so, so good,” he said when he reached the front of the hall. “This is what democracy looks like.”

What it really looked like was charisma. It’s a rare and unstable element in politics — few possess it, and fewer still are able to sustain it through the exhausting ordeal of a competitive campaign. This year, O’Rourke had it, and he was able to harness its great power to overcome the numerous structural disadvantages facing a Democrat running in Texas. He started as a total unknown; by the end, he was on a first-name basis with Texans, and his iconic black-and-white “BETO” logo was everywhere around the state. He started with a little money; he ended up raising a staggering $70 million, largely through the force of his social-media persona. He started off knowing the Republicans would have an organizational advantage; he ended up using his huge fundraising haul to build a turnout machine.

O’Rourke, a former musician, started the campaign talking about his “punk rock” campaign philosophy, vowing to refuse corporate donations and touring Texas by van, as likely to appear at a honky-tonk bar as the Rotary Club. By the end, he was playing arena shows — some 55,000 people came out to see O’Rourke share the stage with the Texan saint Willie Nelson in Austin at a late September rally. In politics, any mildly compelling candidate is apt to be called a “rock star,” but O’Rourke actually performed like one.

Last Sunday, I went to see his final rally in his stronghold of Austin, which was held at a park in a historically Hispanic neighborhood. A few thousand people attended, some arriving on share bikes and motorized scooters, many of them dressed in Beto T-shirts and other stylish merchandise. (For all their weaknesses in Texas, the Democrats do appear to dominate in the realm of graphic design.) The woman standing in front of me, wearing a straw cowboy hat, had a dog wearing a “Barks for Beto” bandana on a leash. The crowd faced an amphitheater stage, decorated with murals depicting scenes of Chicano liberation. A couple of famous Austin singer-songwriters warmed up the crowd.

O’Rourke bounded onstage and gave his stump speech, which at this point was honed down to a crowd-pleasing set list. He talked about overcoming “the smallness, the meanness” of Washington with “this big, bold, beautiful heart that could only come from Texas.” He addressed teacher pay, climate change, and sentencing reform, decrying “a war on drugs that has become a war on people — and some people more than others.” He called for an end to America’s endless military engagements, in Afghanistan and elsewhere. It was, I thought, a speech that you might very easily hear coming from the mouth of a 2020 presidential candidate — something many of his avid supporters hoped he would become.

O’Rourke finished up with a rousing prediction of victory, and then a woman from the campaign came out, to ask the supporters to volunteer to go knocking on the doors of potential Democratic voters. But many of the people in the audience seemed more drawn by the pull of celebrity. A mob swarmed behind the stage, hoping to get a word or a handshake or a selfie with Beto as he departed. “For the few people who are still here,” the woman onstage pleaded, “please take on this very special challenge to get Beto elected.”

O’Rourke was struggling to make his way slowly to his nearby minivan, surrounded by a protective phalanx of female volunteers wearing white T-shirts reading “Ambassador for Beto.” The fans pushed in close to him, holding up cell phones, reaching out to grab his outstretched hands. When O’Rourke finally made it to the car, the crowd nearly pinned him against its door. When he got behind the wheel, they ran around in front, blocking him from leaving. At last, he pulled away, with a few fans running alongside, and headed south to another rally in San Antonio, held at a large music hall. There, the fervent atmosphere was just as overheated.

By the end of the campaign, I had a feeling that, whatever the polls were saying, O’Rourke had a shot to win the race. But even charisma has its limits.

This morning, as the reality of Tuesday’s vote settled in, many Democrats in Texas were in an incongruously triumphant mood. For the first time many of them could remember, on election night, they had seen a Democrat in the lead in a statewide race. Even though it slipped away late, Cruz’s margin of victory — just 2.6 points with 99 percent of the vote counted — was far narrower than most pollsters predicted. O’Rourke ran a better race than any Democrat in a generation, and it wasn’t all for nothing. Down the ballot, he helped to carry two Democrats who flipped seats in the House, and the party gained ground in the state legislature. In Harris County, the populous urban area around Houston, a 27-year-old Latina defeated a long-tenured Republican for the highest local office. O’Rourke also outpaced Hillary Clinton’s performance in traditionally Republican suburban areas, carrying Williamson County, north of Austin, and Tarrant County, around Fort Worth.

“I hate the term ‘woke’ but we are in Tarrant County!” Kris Savage, one of the activists I met at the organizational meeting in January, texted me this morning. “Our entire City Council and mayor are on the ballot again in May.” O’Rourke leaves behind a network of thousands of volunteers like Savage, many of them newcomers to political activism, as well as many more small donors nationwide. Before his event in San Antonio, I asked O’Rourke if he thought this organization could outlive the campaign. “The truth of the matter is, I haven’t built anything — I’ve really plugged into what people are doing on ground all over the state,” he replied. “I think it’s up to all of us to keep it together. It’s not one person, and not one political party.”

It was a practiced politician’s answer, but it was also true that O’Rourke was partly the beneficiary of larger forces unleashed by Donald Trump’s presidency. Take the example of Cari Marshall, one of his most devoted supporters. She is a native Texan who has worked for art galleries and tech companies, and lived for years in California before moving home to Austin. “During the Obama years, I like a lot of people got super-lazy — really embarrassingly lazy — about this stuff,” Marshall told me earlier this year. She threw herself into the Indivisible movement after Trump’s election, staging protests at the office of her Republican congressman.

Marshall first met O’Rourke at fundraiser he held in 2017, at a fashionable hotel in South Austin. She asked him a question about Texas’s troubling maternal mortality rate, which he flubbed. “As he was leaving, he walked right up to me and he said, ‘I am so sorry for that pitiful answer I gave you,’” Marshall recalled. After they talked, O’Rourke started bringing up the maternal mortality issue on the campaign trail. Marshall soon became the driving force behind the Austin for Beto Facebook group, and via social media, helped pollinate similar grassroots groups all over the state.

When we first talked, Marshall was struggling to figure out how to integrate her Facebook activities with those of the campaign, which had recently hired some operatives who had worked for Bernie Sanders to do the fieldwork necessary to target and register potential Democratic voters. “In our group, most of us are not involved in the canvassing, that’s just not our thing,” she said. By the end of the campaign, though, Marshall was leading a group of fellow “ambassadors” — the campaign’s term for its 500 or so most active volunteers — on a “caravan” through ten rural counties. (The irony was intended.)

“I feel like Texas is on the precipice,” Marshall told me on Saturday, when I met her out canvassing in the small town of Lockhart, south of Austin. “I feel so much more hopeful than I did after the 2016 election. I feel so much more powerful.”

I followed Marshall, a slender blonde woman wearing a Beto T-shirt and a matching temporary tattoo on her arm, as she knocked on doors with a friend, Lana Hansen. “If you’d told me then,” she said, referring back to our first conversation, “that six months later I’d be walking the streets of Lockhart ….” We walked up to a house that she was directed to on an iPhone app provided by the campaign, which she’d visited before. The woman at the door, who had told her she wasn’t going to vote, now said she had decided to go to the polls for Beto.

“I just want to hug her,” Marshall whispered as we walked away. The next place didn’t look promising — there was a red Marine Corps flag flying out front. But the woman who answered was voting for O’Rourke, she said. As for her husband …

“I’m trying,” the voter said, plaintively. Her husband was the former Marine. She said they had trouble talking about Trump. She was white, but he was Hispanic. She was outraged Trump’s immigration policies, but her husband didn’t think he was a target of racism. Marshall asked gently if he was worried about the Second Amendment. “That’s his big thing,” the woman replied. “He doesn’t want anybody coming and telling him he can’t own guns.” O’Rourke had said he was proud that his voting record on gun legislation was given an F rating by the NRA.

Marshall had planned to be in El Paso on election night, but she had just canceled her flight, feeling like she couldn’t bear to be there if O’Rourke didn’t prevail. “I will be upset,” she said. “But we knew all along it was a long shot.” Lockhart is famous for its barbecue, so we stopped for some brisket at a restaurant near its charming town square. “I am so thankful to him, because I was so angry after 2016,” Marshall said. “He pulled me back.”

Later, Marshall met some other volunteers for a beer at a microbrewery. There was Lana, and her good friend Kate, whom she had met through the Beto campaign, and Jason, a neighbor she had never known until they both got involved with Indivisible. They reminisced about the resistance days of 2017, talked about the community they had built, and made plans for what they would be doing after the Beto campaign. A younger volunteer talked about trying to take over the Democratic Party organization in her county. “All I can think about,” Marshall told me, “is that shit storm in the Texas legislature that starts again in January.”

Earlier, I had asked Marshall what she thought about the talk — prevalent among the volunteers and Washington commentators alike — that O’Rourke might head right off to Iowa or New Hampshire after the Senate election. “People say he needs to be president, and I was like, hands the hell off people!” she said. “We need him here. Let’s make him senator.”

“Plus,” she added, “Kamala Harris is a badass. Let’s see some of these women.”

The following morning, I had coffee with a respected Democratic strategist in Austin, who wasn’t affiliated with the O’Rourke campaign. “If he wins, I think Beto goes and becomes a great United States senator,” the strategist said — adding that, while that outcome wasn’t likely, it was exciting just to be talking about it as a possibility. There was little chance of him immediately running for president in that case, after criticizing Cruz for doing the same thing throughout the campaign. “If we lose,” the strategist went on, “Beto runs for president.” And in a way, it might be a simpler task if he lost, and was unencumbered by responsibilities in Washington. His message, although a tough sell in Texas, seemed well calibrated for Democratic primary voters nationwide.

“Show me any candidate who has his energy,” the strategist said. “Who has his infrastructure, who is considered an insurgent, a newcomer, and has that amount of enthusiasm behind him.” Most valuable of all, O’Rourke now has a fundraising network, and the most valuable email list in Democratic politics. “It’s the freshest,” she said, full of names of rank-and-file progressives who are “engaged in this shithole moment.”

The next morning, talking to reporters in Houston, O’Rourke ruled out any interest in the presidential race. “I will not be a candidate for president in 2020,” he said in response to a question from MSNBC’s Garrett Haake. “That’s I think as definitive as those sentences get.” But on Tuesday night, after the results came in, he sounded like man who was thinking about unfinished business. Bathed in soft light and wreathed by gossamer wisps from a smoke machine, his voice was thickened with emotion as he shouted into a handheld microphone. “I’m so fucking proud of you guys,” O’Rourke told his campaign workers — unbleeped — on live national television. In a final metaphorical flourish, which will do nothing to dampen speculation, he promised: “We will see you out there, down the road.”

The strength of O’Rourke’s performance has quieted, at least for now, previous criticisms from political professionals about his unorthodox campaign strategy. But the curse of losing narrowly is that there is always reason to wonder about decisions at the margins. This morning, one Democrat who was involved in his campaign questioned O’Rourke’s determination to stick to a statewide campaign strategy all the way to the end. In the last week of October, he held rallies in conservative cities like Amarillo and Tyler. Meanwhile, he spent relatively little time in Harris County in the closing days of the race, holding just one 8 a.m. rally in Houston on the Monday before the election. Although turnout for the midterms was record-shattering in Texas, roughly comparable that of the 2016 presidential year, O’Rourke ended up winning 16,000 fewer votes than Clinton in Harris County. He also failed to match her showing in the Latino-dominated border counties of the Rio Grande Valley. To win, he had to do better there.

For months before the election, Latino leaders were telling O’Rourke he needed to start laying the groundwork for a persuasion campaign. For all of Cruz’s (and Trump’s) hard-line rhetoric on immigration, the Republican started with support in culturally conservative segments of the community, because of his stance on issues like abortion and guns. It also didn’t hurt that he was named Cruz. Many Democratic strategists were perplexed by O’Rourke’s unwillingness to frontally assault Cruz when it came to issues like immigration, or to counter his negative personal attacks. O’Rourke did hit back on one notable occasion, reviving the “Lyin’ Ted” nickname in their last debate, but almost instantaneously said he regretted it.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the political consultants thought O’Rourke would have benefitted from listening to more consultants. Although he had professionals running his online fundraising and field operation — which mounted a large and apparently successful get-out-the-vote effort — O’Rourke was his own chief strategist, and relied on a small circle of aides, some of whom came from non-political backgrounds, and none of whom had run a statewide race in Texas. Unlike Barack Obama, a charismatic Democrat to whom O’Rourke was sometimes compared, he didn’t have a David Axelrod, and he showed little interest in mundane political mechanics. “Win or lose, he’ll be able to say he did it his way,” said the strategist I met in Austin, who admired the success of his “outside the box” strategy. “But the box exists for a reason.”

Nonetheless, it’s easy to imagine how a Beto-style insurgency could be mounted in the early presidential primary states, which are all considerably smaller and more manageable than Texas. The model is sure to be mimicked, and it will surprise no one if, say, next month Cory Booker — another bro-ish liberal with an upbeat message and social-media savvy — sets off across the cornfields of Iowa in a pickup truck. I’m not so sure, though, that Beto himself will run. He has spoken with aching earnestness about how much he has missed his three children during his many months of constant travel. On the other hand, it’s rare for a politician in his position to pass up such an opportunity, and O’Rourke often talks about leading a movement. The magic can be hard to recapture after a rest — just ask Gary Hart, or Sarah Palin.

Evan Smith, the co-founder of the nonprofit news site the Texas Tribune, points out that there is another race O’Rourke could run in 2020. The other incumbent Texas senator, John Cornyn, is up for reelection, and there are rumors he wants to retire. A year ago, any conversation about a Democrat’s statewide chances began with the relative unpopularity of Cruz, but now O’Rourke would start with a base of support, name recognition, a wealth of experience, and that donor list. Smith says that Democrats in Texas had been “living in a hope-free universe,” but the Beto campaign has transformed their expectations. “You’ve got a guy who is maybe a once-in-a-generation candidate,” he says. “Who is able to magnetize the electorate.”

History has a way of finding a use for such charisma.