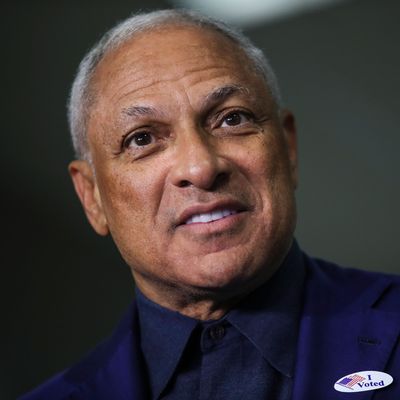

In today’s special election runoff for a U.S. Senate seat in Mississippi, former congressman and U.S. Agriculture secretary Mike Espy is very much an underdog against appointed incumbent Cindy Hyde-Smith. But if he pulls off an upset, he would make some history as just the third African-American to be elected senator or governor since Reconstruction from one of the states of the former Confederacy. He’d be the first African-American southern Democrat in the Senate.

Given Mississippi’s reputation as a bastion of the most violent forms of white supremacy during the Jim Crow era, and its intense resistance to the civil-rights movement, a breakthrough by Espy would be fitting. The state was actually represented during Reconstruction by the only two African-Americans (Republicans Hiram Rhodes Revels and Blanche Bruce) to serve in the Senate until Ed Brooke’s election from Massachusetts in 1966. But Mississippi has been a white conservative Republican stronghold since the civil-rights movement and the enfranchisement of African-Americans realigned the state, which continued to exhibit pervasive racial polarization in politics.

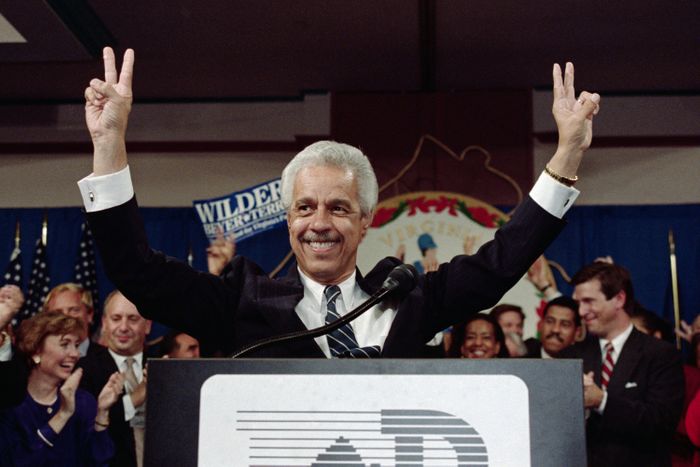

About a third of the electorate in Mississippi (as reflected in the November 6 special election that led to today’s runoff) is African-American, which gives Espy a solid base. However, winning the requisite share of the white vote to form a majority has been elusive for Mississippi Democrats and for African-American statewide candidates throughout the region. The only African-American southern governor since Reconstruction was Virginia’s Doug Wilder, elected in 1989; like Espy, Wilder was known to take conservative positions (particularly on the state budget and crime policy) from time to time. And the only African-American southern senator in modern times is an actual Republican, South Carolina’s Tim Scott, who was appointed to his seat by Governor Nikki Haley in 2013, then reelected in 2014 (to the remainder of a term) and 2016 (to a full term).

By and large, the Espy–Wilder approach of seeking to occupy the center of the political spectrum has been standard for southern Democrats of both races in the post-civil-rights period. But it hasn’t produced many success stories for African-American statewide candidates. Black Democrats have won Senate nominations in North Carolina (Harvey Gantt in 1990 and 1996), South Carolina (Joyce Dickerson in 2014 and Thomas Dixon in 2016), Georgia (Denise Majette in 2004 and Mike Thurmond in 2010), Tennessee (Harold Ford in 2006), and Texas (Ron Kirk in 2002). Gantt (twice) and Ford ran competitive campaigns, while the rest lost by landslides of various dimensions. It’s significant that overt racism was most evident in Jesse Helms’s campaigns against Gantt, and Bob Corker’s campaign against Ford. The race card is something white southern conservatives don’t like to play unless they need to (though implicit racism, of course, is marbled through southern GOP policies and messages like fat in a steak, particularly in the Trump era).

As Jamelle Bouie once explained, African-American pols are often placed in a career trap that makes them less viable than they might be in statewide contests:

Despite the attacks that took down Gantt and Ford, outright racism isn’t the main reason that keeps African Americans locked out of the highest statewide positions. Rather, it’s the accumulated effects of long-term racial discrimination—the limitations associated with representing heavily black House districts or leading majority-black cities—that block further advancement. If black politicians almost always represent black constituencies, it’s because of historic housing patterns shaped by discrimination. If black constituencies are typically less affluent than their white counterparts, it’s because more African Americans are still in low-income brackets, another product of discrimination.

Espy represented the majority-black Second Congressional District of Mississippi from 1986 until 1993 (when he stepped down to become Bill Clinton’s Agriculture secretary). His Cabinet service probably enhanced his “mainstreaming” as a suitable statewide candidate with centrist credentials. But it also embroiled him in a pseudo-scandal (an over-the-top special prosecutor investigation that forced him out of the Cabinet, although he was eventually acquitted of corruption charges) that Republicans are still using against him.

It’s interesting that Espy is deploying the old-school centrist approach in the same year when African-American gubernatorial candidates in Florida and Georgia broke the mold with more progressive campaigns based on mobilizing poor and minority voters and defying traditional conservative hegemony in both parties. Stacey Abrams of Georgia and Andrew Gillum of Florida fell just short of victory, while doing better than their white or black Democratic predecessors or counterparts have recently done. Mississippi is most definitely different from those states; there’s no abundance of upscale suburbs teeming with transplanted tech employees to give Democrats a progressive white base. So Espy is playing the hand he’s been dealt. But like Abrams and Gillum, his candidacy could make history in his state and the entire region. And in Mississippi, old times might be forgotten for a brief but morally satisfying moment.