Nearly 17,000 people have now lost Medicaid coverage in Arkansas due to the state’s onerous work requirements, according to state data released Monday. That’s up from 12,277 in October, continuing a trend that analysts directly attribute to the structure of the state’s Arkansas Work program. While the program’s defenders in state and national government describe Arkansas Works as a model for other states, as well as for federal policy, their motivations for doing so should now be obvious. The state’s version of means-testing — policy that ties the level of social welfare a person receives to their income bracket or employment status — has penalized thousands of people for being out of work or for working irregular hours. Arkansas saves money on welfare, but as other, similar means-tested reforms demonstrate, needy people will bear heavier burdens as a result.

As KUAR Public Radio reported, Arkansas implemented an idiosyncratic version of Medicaid expansion. “Many Republican-leaning states chose not to expand their populations. Arkansas did, but instead of simply expanding Medicaid, it used mostly federal funds to purchase private health insurance for those lower-income individuals,” KUAR explained. Arkansas also applied for and received a waiver from the Department of Health and Human Services’ Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to attach work requirements to its program. Beneficiaries must work at least 80 hours per month and submit proof of work, study, or community service to the state every month online in order to remain enrolled in Medicaid. If a person doesn’t meet these requirements three months in a row, they lose coverage, and must reapply the following January.

In theory, the state can grant a “good cause” exemption to beneficiaries who can prove that mitigating circumstances prevented them from meeting work requirements. But in practice, the state appears to have handed out few such exemptions, even though structural challenges sometimes prevent beneficiaries from accessing the state’s computerized reporting system. Many low-income people lack reliable internet access, especially in rural areas of the state. Officials only allowed people to report the hours they worked over the phone in December. That’s the same month the state began advertising Medicaid expansion to residents — a full six months after the program technically launched.

The National Health Law Program, along with Legal Aid of Arkansas and the Southern Poverty Law Center, filed a suit to block the state’s work requirements in August, arguing that the policy counters Medicaid expansion’s intended purpose, which is to make health care more affordable for the poor. Two of those groups — the Southern Poverty Law Center and the National Health Law Program — filed suit against a similar work requirement program in Kentucky. In that suit, a federal court initially ruled against the state and sent Kentucky’s planned work requirements back to the Department of Health and Human Services for review. The Trump administration proceeded to reinstate Kentucky’s work requirements in November. In an approval letter, HHS proclaimed that “there is little intrinsic value in paying for services if those services are not advancing the health and wellness of the individual receiving them, or otherwise helping the individual attain independence.”

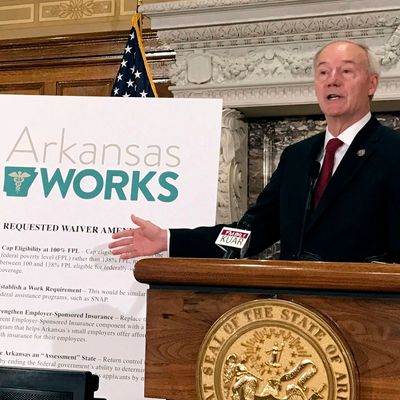

Arkansas’s Republican governor, Asa Hutchinson, expressed a similar conviction in January, when he announced that CMS had approved the state’s waiver. Arkansans “understand the dignity of work,” he said in a press release; work requirements would, he added, “go a long way to create opportunities for able-bodied working-age Arkansans to enter into training or employment and ultimately climb the economic ladder.” But the act of requiring a person to work does not create a job for them at the same time; there is no magic here, only sleight of hand. Poor people know that they’re poor. Why else apply for Medicaid? The subtext — that the poor need to be reminded to sell their labor for profit — is loud, and it makes for punitive policy. Hutchinson has rejected that characterization of the state’s work requirement regime, but the implications are clear. The policy works as intended, and the intention is to punish the poor for perceived failures.

But Arkansas’s program is still useful in one respect. It illustrates perfectly the cruelty of using healthcare, or any survival need, like a carrot to bait the poor. Some versions of means-testing are less draconian than others, but they all exists on the same policy spectrum; a line connects Bill Clinton’s version of “welfare to work” to Asa Hutchinson’s Medicaid innovations. The truth is that as long as policymakers treat poverty like a moral condition, which can be relieved by goading low-income individuals into making better lifestyle choices, immense structural inequalities will persist. There is not a welfare policy on the planet that can distinguish, fairly, between the deserving and the impure. Employment or lack thereof is no measure of character.

What we do know, however, is that means-testing leaves thousands of needy people unable to access basic social services. Clinton’s Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program, which converted federal welfare funds to block grants to states, and implemented work requirements, failed to meet the challenges of poverty. The Center for Budget and Policy Priorities reported in November that since 1996, the year Clinton created TANF, “its reach has declined dramatically.” “ In 2017, for every 100 families in poverty, only 23 received direct financial assistance from TANF — down from 68 families in 1996. This ‘TANF-to-poverty ratio’ (TPR) reached its lowest point in 2014 and has remained there,” CBPP continued.

As was the case for welfare reform, the consequences of booting people from Medicaid may take years to fully reveal themselves. Arkansas may provide quite a bit of data in the future. The state designed its work requirement regime to be phased in, age bracket by age bracket. Starting in January, Arkansans ages 19 to 29 will be subject to the same requirements that have already booted thousands of older residents off the program.