In May of 2017, a 26-year-old social-media marketer named Peter Galanko made an investment in Verge, a little-known cryptocurrency trading under the symbol XVG. At the time, the great cryptocurrency mania, which saw Bitcoin climb 25-fold by the end of the year – it would fall all the way back to a fifth of its December 2017 peak by the end of 2018 – had only just started to heat up. Verge was just one among thousands of nearly indistinguishable digital currencies that traded at a fraction of a penny. But soon after Galanko got in, Verge took off like a runaway balloon, corkscrewing up to half a cent by late August. Galanko, who’d taken to styling himself @XVGWhale on Twitter, had more than quadrupled his money. But now he had an idea for how he could do even better: He needed John McAfee.

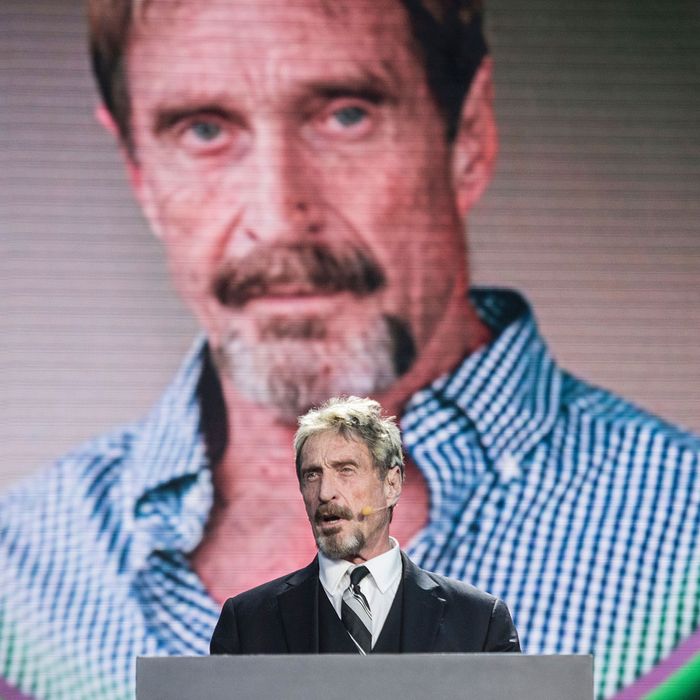

The Rocky Mountains were dappled in autumn yellow as Galanko and his girlfriend set out on the two-day cross-country trip from Colorado to rural Tennessee. Their destination was the home of McAfee, the 72-year-old antivirus software multimillionaire who, after escaping from a police investigation into the violent death of his neighbor in Belize in 2012 and boasting in graphic detail about his adventures with the powerful drug bath salts, had transformed himself into a public figure “who many see as a well-respected cryptocurrency soothsayer,” as Slate magazine put it. In mid-July, McAfee had tweeted that Bitcoin, then trading at around $2,300, would be worth $500,000 by 2020, and that if it were not, “I will eat my dick on national television.” By the end of August, the price had more than doubled, and many took this as evidence of McAfee’s foresight. Galanko figured that a good word from McAfee about Verge — whose market would be easier to influence than Bitcoin’s vastly larger one — could send the value of the cryptocurrency dramatically higher.

McAfee had promised an hour of his time, according to a long video Galanko later posted about the encounter on YouTube, but appeared perplexed when the couple showed up at his door. “Who are you?” he asked with a baffled expression. “I didn’t invite anyone over today.” Galanko’s spirits sank, but not for long: a grin spread across McAfee’s weather-beaten face as he let on that he was just playing one of his trademark pranks. With a hearty handshake, he invited them inside.

At first Galanko felt anxious, intimidated by McAfee’s fame and force of personality as well as by the home’s contingent of armed security guards. But as they settled down to talk, Galanko was soon drawn in by McAfee’s skillful storytelling. The evening rolled by in whiskey and conversation. Galanko and his girlfriend wound up staying for a week. The men shot guns together, and Galanko tweeted snapshots of himself riding in the back of McAfee’s car and of McAfee cooking breakfast.

“It was an amazing opportunity … he’s a genius,” Galanko later gushed in the video. (He declined to talk to New York for this article.) The only thing missing was the thing he’d come for. When Galanko asked McAfee to publicly endorse Verge, he demurred, explaining that he was already committed to a rival coin. But a couple of months later he came around, tweeting on December 13 to his 700,000 followers that Verge “cannot lose.” McAfee’s praise was like a match to a rocket fuse. Verge’s price nearly doubled overnight, and by the end of ten days it was up 2,500 percent, making it one of the most successful cryptocurrencies of 2017. A single dollar invested at the beginning of the year was worth more than $10,000 by the end of it.

Among the self-promoting “experts” who appeared to offer investment advice during the great crypto boom, McAfee’s only real competition was James Altucher, the lifehacking guru turned “Crypto Genius” whose advertising plastered every nook and cranny of the web in late 2017. But McAfee had the better tech credentials (having founded a software company that sold to Intel for $7.7 billion in 2010), the larger Twitter following (700,000 versus 200,000), and the bigger personality (he has bragged about using cryptocurrency to pay for drugs, porn, and hookers). He was also the only one slated to be played by Johnny Depp in a movie about his life (Depp has since been replaced by Michael Keaton).

Recently a drug-crazed libertine on the lam, McAfee had turned himself into a drug-crazed libertine genius who had seen the future of tech once and was going to do it again. Like Donald Trump, he used social transgression to earn himself a rabid fan base that reads his don’t-give-a-fuck attitude as intoxicatingly badass and authentic – but while Trump once bragged that he could kill someone and his base wouldn’t care, McAfee may have actually done it. For his fans, McAfee represents the incarnation of libertarian id fulfilment — living proof of what a person can achieve if unconstrained by bosses, teachers, wives, and moms. His place in their hearts was pithily summarized in a tweet that Peter Galanko sent shortly before his first meeting with McAfee: “You are a pioneer and symbol of freedom.”

Combine a volatile, libidinous personality with a throng of admirers who mistake their hero’s disorder for genius, and you have the makings for a chaotic denouement. In McAfee’s case, the events that would ensue included death threats, lawsuits, SEC investigations, billions of dollars of investor value created and destroyed, a not-entirely-in-jest presidential bid, and shitstorms both literal and figurative.

McAfee’s path to cryptocurrency was circuitous. He first became a household name thanks to the eponymous antivirus software firm that he founded in 1989, and which made him rich when he sold off his shares in the mid-1990s. When Bitcoin, the first decentralized cryptocurrency, was created in 2009 by a still-anonymous software engineer going by the pen name of Satoshi Nakamoto, McAfee was living in the desert of New Mexico, where among other things he attempted to create a sport called aerotrekking based on ultralight aircraft flying low over mountainous terrain. Then he moved to Belize, claiming that the fallout of the 2008 economic crisis had wiped out 96 percent of his net worth, a story which made him a perfect media symbol of the era. (It turned out to be a ruse to avoid a multimillion-dollar wrongful death suit filed by the family of a passenger on a McAfee aircraft that flew into the side of a canyon in Arizona — the pilot, who was McAfee’s 22-year-old nephew, also died in the crash.)

In Belize, he lived in luxury, hung out with gangsters and prostitutes, started ingesting powerfully mind-altering bath salts and, according to his driver, Tom Mangar, ordered a beating that left a man dead. Mangar told me that after McAfee got into a dispute with a black Belizean neighbor named David Middleton in 2011, McAfee called Mangar and asked him to hire three thugs to beat Middleton up. Mangar obliged, and the ensuing attack was so violent that Middleton died in hospital. (I detailed the incident in my 2016 Showtime documentary, Gringo: The Dangerous Life of John McAfee. McAfee denied Mangar’s account and created a website which he said would refute the documentary’s claims, but has yet to offer any substantial evidence there, although he did complain that director Nanette Burstein had paid certain interview subjects for their participation.)

Things didn’t get really hot, though, until his white American neighbor was murdered in 2012, a crime for which McAfee was last month held legally liable on default in a civil wrongful-death suit filed in Florida by relatives. McAfee went on the run with the help of Mangar, to whom he’d promised $100,000 and a truck if he’d get him out of the country. After turning the escapade into an international news sensation, McAfee was arrested in Guatemala and then deported back to the U.S. Once safely home, he stiffed Mangar, who claimed he had to give up his own car to pay back debts he’d incurred during the escape. Mangar, enraged, decided to go public with the story of Middleton’s death.

Moves to Portland, Montreal, and eventually rural Lexington, Tennessee, followed, as did a sex worker named Janice Dyson, whom McAfee began calling his wife. McAfee recorded videos of himself shooting off guns, and on social media recounted run-ins with shadowy hit men who he believed were trailing him. By now, having turned 70, he was visibly frail and rheumy-eyed, with a noticeable slowness to his speech.

But McAfee wasn’t finished yet. He began a methodical and savvy reboot of his public image. Recognizing that the straight-shooting do-gooder image he’d cultivated when he first moved to Belize — where he talked about trading carefree wealth for a life spent helping search for herbal medicines in the jungle — was out the window, he instead began shaping a new persona. He bragged that he had faked a heart attack to avoid deportation from Guatemala and claimed that he had bugged a huge number of public officials in Belize. In 2013, he released a widely watched YouTube video in which he snorted white powder and cavorted with a bunch of scantily clad women while advising viewers to uninstall McAfee AntiVirus from their computers.

Meanwhile he pushed back hard on the truly damning allegations, telling every journalist he talked to that he had not been involved with the death of his neighbor, but was the victim of an elaborate plot by the Belizean government. The press played along. They mostly avoided hard questions and ID’d him using value-neutral labels like “security software pioneer” and “eccentric millionaire.” McAfee was occasionally described as “controversial,” but just as often was a “genius” and “brilliant.”

By the beginning of 2015, McAfee was back at full throttle. He went into business with a tech incubator called the Round House in the Alabama town of Opelika, a six-hour drive from Lexington. “This is a new phase in my life — getting back to building things,” he told USA Today. Under the aegis of a company called Future Tense Central, McAfee started scouring the area for cybersecurity products to acquire. One of the first additions to his portfolio was a program called D-Vasive, the brainchild of a local septic-tank cleaner named John Clore. As McAfee went about his work, he was trailed by a camera crew shooting a reality show for Spike TV. To amp up the stakes, he decided to run for president on the Libertarian ticket, and wound up doing surprisingly well, with a third-place finish.

The payoff for McAfee’s efforts came in early 2016, when an investor named John O’Rourke put him in touch with Robert Ladd, the president of a penny-stock company called MGT Capital Investments, Inc. Ladd and O’Rourke both felt that McAfee’s notoriety could bring MGT some much-needed attention. Until recently the company had been in the online fantasy-gaming business, but Ladd had sold off those assets. At this point MGT was essentially an empty shell company with only one thing going for it: It was listed on the New York Stock Exchange, which lent it respectability and access to a large base of potential investors.

Ladd approached McAfee and suggested that he come aboard as the company’s chairman and CEO. With a bold-faced name at the helm, MGT would be rebranded as a cybersecurity company. As was alleged in a subsequent investor lawsuit, the deal offered McAfee a salary of $250,000, a consulting fee of $250,000, and a bonus based on future stock price. In addition, MGT would buy D-Vasive and another of the companies in Future Tense Central’s portfolio. To make the deal work, MGT needed more money, so a group of investors led by Florida speculator Barry Honig agreed to front $850,000 for the venture in return for 18.8 million shares of MGT stock.

None of MGT’s products ever made it to market, but that wouldn’t have mattered to Honig, whose specialty was penny-stock pump and dumps – the practice of manipulating the share price of thinly traded stocks so as to make them seem like exciting investments to gullible investors, then taking a profit. This time, the operation would be supercharged by the high profile and media savvy of John McAfee. But according to the lawsuit, Honig and his co-investors were the suckers, because MGT under McAfee’s management never issued the shares he was promised.

The deal was inked that May, and over the course of the next eight days, MGT shares climbed more than eightfold, from 37 cents to $4.15 per share (Honig & Co.’s shares at this point would have been worth $80 million). While insiders pumped the stock, as the SEC charged in September 2018, the press ran headlines like “John McAfee’s Mysterious New Company Is the Hottest Stock In America Right Now.” The run-up earned McAfee a bonus of $600,000; Clore, too, stood to profit handsomely. When McAfee called to tell him about the deal, a faulty coupling had just doused him in raw sewage. “I’m riding in the truck covered in feces, he calls me up and says he has this potential deal for you, are you interested? I say, ‘Hell, yeah.’ I’m kind of in shock because I’m covered in feces.”

Behind the scenes, though, McAfee’s focus was less than laser sharp. For one thing, despite his public claims to have “fucking invented cybersecurity,” he had never really been very technically sharp. Veteran computer-security researcher Dr. Vesselin Bontchev, who studied McAfee anti-virus software back when McAfee was writing it, opined on Twitter that “McAfee was the same technically incompetent schmuck that he is now. It’s not age or drugs that have damaged him — he has always been this way.”

Massive drug use was not helping, either. For a while, after falling off the wagon, McAfee had pretended to be a teetotaler, but now he was drinking lustily in public. He was still on bath salts, too — this time a variant of bath salts called alpha-PHP that he ordered from a supplier in China. Among the drug’s symptoms are delirium, hypersexuality, and persistent paranoia. Before an important shareholder meeting in September 2016, he spent four straight days on a alpha-PHP–fueled sex binge.

A rift opened up with Honig and the other backers, as alleged in the lawsuit, when McAfee decided that, given the run-up in share price, the terms of the deal inked in May were now too generous to the investors. When Honig went to meet with McAfee at MGT’s headquarters in Durham, North Carolina in October, he was greeted by a whiteboard on which a single number had been written: “$11.655 million.” McAfee told Honig that he and the other investors would need to invest this much more money if they wanted to get the shares allocated to them in the agreement.

While Honig was pondering that demand the next day, his lawsuit claims, McAfee texted him to clarify his position. If Honig and the other investors did not meet his demands, he wrote, “I promise you it will be the last time that you and I ever speak.”

Honig didn’t bite, but it hardly mattered. The spike in MGT’s share price was melting away. Five days later, the New York Stock Exchange announced that it intended to delist MGT. The company’s stock price nose-dived, taking with it the fortunes not only of principals like Honig and McAfee but of smaller shareholders like John Clore. “I’m back to square one,” noted Clore ruefully. “Have to go back to pumping shit.”

MEANWHILE, BACK IN crypto world things were getting heady. After bumping along below $500 for several years, the price of Bitcoin started to tick upward in the second half of 2016, and in January 2017, it crossed above $1,000. As the market soared, it spurred developers to introduce new cryptocurrency tokens, the so-called altcoins. Among the raft of new offerings entering the market was Verge, a copy of an earlier coin called Dogecoin that had originally been intended as a comic riff on the ubiquitous Shiba Inu meme but then wound up climbing in value. Retaining no trace of the original’s whimsicality, Verge was built around security features aimed at protecting users’ identities.

McAfee had appointed Bruce Fenton, the Executive Director of the Bitcoin Foundation, to MGT’s Cryptocurrency Advisory Board a month after taking over in 2016, and a couple of weeks later he announced plans for MGT to build a Bitcoin mining operation. As time went by, the company got more machines and spent less time talking about its security products, none of which ever came out anyway. Now, as he touted the altcoin boom as a way to turn MGT around in May 2017, the Zen-like detachment from money that McAfee had claimed in 2009 disappeared. The new public persona was pure Ayn Randian Übermensch. “I don’t know anyone more capable than me,” McAfee bragged to Bloomberg News. “I have never lost in terms of business and I certainly don’t intend to start now.” His famous Bitcoin price call came six weeks later.

The thing about Bitcoin mining, though, is that it’s the least sexy part of cryptocurrency. It involves employing large quantities of computer hardware to turn vast amounts of electricity into heat under the guise of solving math problems, with Bitcoins being produced from time to time as a side effect. From an environmental perspective, it’s the digital equivalent of mountaintop-removal coal mining. The profit margins tend to be narrow, and as a pure business endeavor, it’s as entertaining as running a server farm.

The real action is in speculation. Prices swing wildly for unknown reasons. To endure a terrible loss, and then see it mysteriously transform into a terrific gain, is intoxicating. And then there’s the potential for profitable shenanigans. Many cryptocurrency exchanges are virtually unregulated, and awash with price-manipulating strategies that are banned on stock and commodities exchanges.

As Bitcoin’s price climbed and climbed through 2017, a familiar bubble psychology took hold. People heard stories of others doubling, tripling, quintupling their money and told themselves there was still time to get in. Just as with every other recent bubble — gold, tech stocks, subprime mortgages — greed crowded out reason. The difference this time was that there was no underlying asset; the mania was for inscrutable abstract ideas that rose only because they had a reputation for rising.

The complexity and opacity of cryptocurrencies, the near-total lack of regulatory oversight, and the willingness of many investors to suspend critical thinking all contributed to a fantastical fluorescence of scams. Not for the first time, a concept born of the desire for openness and transparency had drawn opportunists operating without moral or ethical restraint. The world of cryptocurrencies, in other words, had become a sort of digital Belize, a place where unscrupulous schemers could do anything to everybody and no one could do anything about it.

For many small investors, the persistent taint of skullduggery surrounding cryptocurrency was less a deterrent than an attractant — a tantalizing hint that, as in Las Vegas, all sorts of delicious but not entirely ethical fun might take place. Whereas pump and dump is illegal in regulated markets, in crypto it went on openly, with investors posting invitations for co-conspirators to join flash mobs to drive up the price of a coin and then all (theoretically, at least) sell and book profits together. Those who complained about the legality or ethics were accused of spreading “FUD,” or “fear, uncertainty, and doubt” — i.e., being buzzkills.

Amid this crowded bazaar of dubious dealing, it was a major challenge for new altcoins to distinguish themselves from thousands of competitors. One trick was to have someone famous shine a spotlight on you for a moment to create the sensation that you might have some upside, enough to draw in some buyers, who would send the price up, which would draw in more buyers, and so on. Floyd Mayweather, DJ Khaled, and Paris Hilton all touted cryptocurrencies. The practice alarmed the SEC enough that last November it issued a statement reminding the public that “endorsements may be unlawful if they do not disclose the nature, source, and amount of any compensation paid, directly or indirectly, by the company in exchange for the endorsement.” (The SEC went after Mayweather and Khaled and reached settlements with both men, with Mayweather agreeing to pay $614,775 and Khaled $152,725.)

Though McAfee had not been an early adopter of crypto, by chance he had happened to craft the perfect persona for touting it. He had both a credible claim to technical expertise and enough of a moral taint to come across as savvy. Just as candidate Trump claimed that he alone could clean up the swamp because he had decades’ experience buying off politicians, McAfee’s self-advertised misbehavior made him plausible as a guide to a marketplace awash with con artists. More to the point, his predictions kept on turning out to be right. After his bullish Bitcoin pronouncement was followed by a steep rise in the market, he doubled down, saying the price would go to $1 million. Sure enough, it rose even more. He started recommending other coins, first on a weekly basis, and then every day.

“John McAfee Appears to Move Cryptocurrency Markets With a Single Tweet,” marveled a Motherboard headline, over an article which declared that “tweets from McAfee were reliably correlated with price spikes that sent cryptocurrencies worth pennies — even fractions of a penny — temporarily shooting upwards in value anywhere from 50 to 350 percent.”

McAfee’s power was incredibly valuable, and he felt he deserved to capture that value. During Galanko’s visit with him last fall, he demanded that Galanko pay him for supporting Verge. Galanko declined, according to screenshots of their conversations that were posted on his Twitter account and later taken down. He was an investor and an enthusiast, but not a member of Verge’s development team. He explained that since all Verge holders would benefit, he shouldn’t have to pay out of his own pocket.

Months later, McAfee brought up the subject again. Galanko responded that he would talk to the developer of Verge and other investors to see if they could put an offer together. But before he could do that, McAfee began promoting Verge anyway. Three days after his December 13 tweet he did a phone-in interview with “The Larry and Joe Show,” a YouTube series about cryptocurrency, on which he said that “in a few months it is going to be the sickest coin on the friggin’ market.”

In the wake of McAfee’s recommendation, Verge’s share price climbed 1,800 percent. On December 21, according to the screenshots on Galanko’s Twitter account, McAfee texted Galanko that he deserved to be compensated. “No-one offered me a fucking penny for 2 billion dollars in market cap increase,” he wrote. (In the previous eight days, the total value of all outstanding Verge coins had climbed from $130 million to $2 billion.) McAfee added that other altcoins had paid him millions for their support and that if he was not compensated with 2,500 coins of the cryptocurrency Ether (trading symbol $ETH, an amount then worth $2 million) he would retract his endorsement.

“People will see that my power to demolish is ten times greater than my power to promote,” he wrote. “I promise that VERGE will be one quarter of what it was before I promoted it.”

The next day, per the screenshots, McAfee wrote again to press his demand: “It’s after 5. Here’s my tweet that’s ready to go; ‘I apologize to my followers, for my support of Verge. It was based on a huge miscalculation. The number of Verge coins in circulation cannot ever justify a price of greater than $0.005. I am extremely sorry for my error.’ Peter … I supported Verge based on your request. I expect reasonable compensation.”

Galanko felt cornered. He had never discussed a specific price for McAfee’s endorsement, and couldn’t afford what McAfee was asking. He consulted with the founder of Verge, Justin Vendetta, a.k.a. Sunerok, but Vendetta said he didn’t have the necessary resources, either. So Galanko texted McAfee an offer worth $70,000.

McAfee fired back: “I’m sorry. Your proposal is unacceptable.” He then made a counterproposal dramatically lower than his first demand. “If you send $100,000 in Ether I will not tweet, but do not ever ask for my help again. Otherwise, if you believe you will recover after my tweet then you are smoking something … I will give you one hour to consider.”

Galanko refused. On December 27, McAfee took to Twitter to declare that his Twitter account had been hacked and that some of his past recommendations had not been written by him. “I have haters. I am a target,” he wrote. “People make fake accounts, fake screenshots, fake claims.” He suggested that Verge was overvalued, and two days later attacked it more directly: “I recommended Verge when it was less than a penny — saying it might rise 100% to two pennies. The price has been wrongly pumped beyond reason.” Having started the day at 17 cents, Verge finished it at 14. Nearly $300 million had been wiped off its market cap.

Galanko decided to fight back. On December 30 he tweeted screenshots of the text messages McAfee had sent him the week before, explaining: “I didn’t want things to go in this direction, but this is the reason for the #McAfee $XVG FUD. He told me the day before I met Sunerok, that he wanted $1.1 million worth of $ETH, within 24hrs. We didn’t pay him. Hence FUD. These are real, he may claim ‘fake’ or ‘hack.’”

Now it was on. McAfee likes to project an air of devilish insouciance, but when he feels attacked he can fight like a honey badger. Whatever happened next happened behind closed doors. Neither man has spoken about it in public, or agreed to discuss it with New York. But Galanko soon after deleted his December 30 tweet, and on January 3, he posted a brief clip to YouTube that he had shot in a darkened room. In it, his pale, smooth-cheeked face appears dimly illuminated by a single lamp and his cell-phone screen, as if during an air-raid blackout. “Hey what’s up YouTube,” he began. “I’m just making this video because a few minutes ago somebody logged onto my Twitter account … the most recent tweets on my page are not mine.” He turned the phone to the camera to show a cracked screen displaying his Twitter feed and claimed that he could not access his own account. “This right here is a fake tweet, it’s not mine. Post it on Twitter, post this video on Twitter, peace out.”

When he resurfaced on Twitter the next day, it was under a new handle, XVGWhaleReal. His old one, XVGWhale, had been deactivated. “I would never FUD $XVG myself,” he wrote. “I’m seeking legal action against the hackers.”

Galanko and McAfee never cooperated again.

IN RETROSPECT, McAfee’s tiff with Galanko was like two men dueling on the deck of the Titanic. The decline of cryptocurrencies continues to this day, and the giddy sense that anything is possible has vanished. How much of Verge’s decline is actually due to McAfee’s influence and how much to the general crash of cryptocurrencies is impossible to say. Maybe McAfee’s crypto-power was just lucky timing all along. A tweet that he sent out last December 7 sounds like it’s from a different era:

“Those of you in the old school who believe this is a bubble simply do not understand the new mathematics,” he wrote. “Bubbles are mathematically impossible in this new paradigm.”

This is nonsense, of course. It’s entirely mathematically possible that the price of Bitcoin will go right back to where it started: zero. Altcoin developer Jackson Palmer thinks crypto prices will play out like they have after past spikes, with people gradually losing interest as the hype leaks away. “I think it’s just a slow decline,” he says, “and then hopefully we get back to the technology.”

As for McAfee, the deflation of the cryptocurrency bubble has done little to crimp his style. He continues to churn through a series of ventures, making great promises, then leaving them to crash or fizzle and recede into the flotsam of past escapades. He declared that he would start to charge $105,000 per tweet to endorse cryptocurrencies; a month later, he announced he was launching his own cryptocurrency. Nothing came of either idea. Later, McAfee offered $250,000 to anyone who could crack an “unhackable” cryptocoin wallet he was backing. It was hacked within days. McAfee refused to pay up.

His personal life, too, has been full of incident. At one point he interrupted intercourse with Janice to pull out a gun and shoot up a crawl space after suspecting that it had been infiltrated by assassins — then bragged about it to the media. This past June he was hospitalized, unconscious for two days after, he claimed, “My enemies maged [sic] to spike something that i ingested.” In September he posted a video on Twitter stating that, yes, he had taken bath salts, “every fucking one of them.” His “controversial genius” persona is now so firmly established that such antics only reinforce the brand. The press gamely play along, with varying displays of credulity: An entertaining tale, after all, is an entertaining tale.

When McAfee announced that he had decided once more to run for president, The Week reported it as an eye-roll-inducing publicity stunt from everyone’s favorite wacky uncle. “One look at this eyepatched man,” wrote Kathryn Krawczyk beneath a picture of campaign manager Rob Loggia looking like a strung-out pirate, “and you’re surely intrigued.”

At first McAfee, too, took a light approach, treating his candidacy as another of his signature pranks. “Let’s be real,” he tweeted. “No sane person could believe I could ever become President.” But within 24 hours he pivoted, writing: “Those who believe my presidential run is a publicity stunt take note: I ran a serious campaign in 2016 under the Libertarian banner, at great cost in time and resources. I am twice as committed this time. Anyone who thinks otherwise does not know me.”

He might be in earnest, and he might even have a chance; at this point in the history of the United States, it’s not clear if anyone is unqualified to be commander in chief. If he really wants to be president, though, his accumulated legal troubles could create headwinds. In 2014 he lost the aerotrekking wrongful-death lawsuit and was slapped with a $2.5 million judgment that he has been eluding ever since. And in September the SEC announced that it was filing charges against Barry Honig, Robert Ladd, and eight other associates for their role in pumping-and-dumping the company’s stock. “As alleged, Honig and his associates engaged in brazen market manipulation that advanced their financial interests,” declared the SEC’s Sanjay Wadhwa in a press release, “while fleecing innocent investors and undermining the integrity of our securities markets.” McAfee wasn’t named in that complaint, but New York attorneys from the Rosen Law Firm launched a class-action suit based on the SEC filing that added McAfee to the list of defendants on the basis of his role as the company’s CEO.

When confronted about his deceptions, McAfee tends to claim that he was only joking, or else responds with threats. Sometimes he does both. As I was preparing this article, McAfee emailed me: “Give it up asshole. You couldn’t distinguish a joke from a turd. You are still on my ‘sue you’ radar. I promise, Jeff, I am going to financially destroy you. If it’s the last thing I do. You manufacture your own truth and peddle it. Be careful signing for letters at the post office.”

Such tactics are unlikely to work against the SEC or against the plaintiff’s attorneys who have their sights on McAfee’s earnings. Nor, in the long run, will they help to support the market value of the enterprises that McAfee promotes. The price of MGT Capital now stands at $0.09, a 98 percent drop from its 2016 high. Over on Facebook’s “$MGT Stock Discussion Board,” which once buzzed with McAfee fans enthusing over the prospect of huge profits but then fell into disuse, the SEC filing caused a reawakening. “Sorry to say this stock has always been a scam,” wrote Facebook commenter Cheryl Emerson. “Get out as soon as you can.”

Over on McAfee’s Twitter feed, however, enthusiasm has been running as high as ever. In October, McAfee posted a 36-second video clip of two of his security guards writhing on the floor after “undergoing mandatory Tazering as part of their employment test.” The tweet garnered 130 comments and 228 likes from his 858,000 followers within three hours. Ever attentive to his base, McAfee responded to many of the comments individually.

“holy fucking shit… lol love it,” wrote @ColCustard.

“I would take a taser for McAfee to get a gig on his campaign team, even if I was the cleaner,” wrote @thumbtacklist.

“badass,” wrote @luc_he.

“hahahaha You’re freakin nuts John!!” wrote @Cryptoholdings.

“you are one of a kind mr. PRESIDENT. LOL,” wrote @cadillacjoe2001.

“You crazy fuck,” @Cryptopatrick77 wrote.

To which McAfee replied: “Indeed.”