The aging process is hard on all of us. The joints bark and moan every time you get out of your desk chair. You have no idea who any of the performers on New Year’s Eve are anymore, as if you could stay up that late anyway. Your old rock gods are beginning to look suspiciously like your uncles. You caught yourself trying to explain Friendster to your niece. It’s quite a journey.

But I’d argue one of the hardest parts of aging, as a sports fan, is watching your beloved villains, the players you’ve delightfully hissed and booed at, begin to gray around the temples and become, in their own advanced age, not the hated targets of your impotent (but quite emotionally healthy!) rage, but instead respected, almost wizened figures of empathy. My first example of this was Brett Favre. I spent 20 years despising Favre — not as a human being, though there would have been good reason for that too — as an avatar of everything I disliked about the NFL (the relentless “he’s a gunslinger!” hagiography of a reckless turnover machine, the breathless will-he-won’t-he Retire Watch stories, those ubiquitous Wrangler commercials — only to watch him, as his career wound down, develop a bit of late-in-career halo. Favre, as his career finally ended, was given an Old Cowboy send-off, treated as a proud warrior, a legendary gunman who finally ran out of bullets. I, and just about every sports fan I knew, spent about two decades booing Favre the minute he showed up on our televisions, but when he hung up the cleats, we were expected to salute and applaud, particularly when he was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2016 to universal acclaim and reverence. It was awful.

(If you’re looking for a reason to still dislike Favre, though, he provided a good one this year.)

In the end, our villains become harmless, their careers becoming metaphors for our own lives. We will all eventually grow old and die, something athletes do in handy, compact fashion, essentially finished and useless to us at the age the rest of us are still figuring out what we’re doing with our lives. (Former NFL MVP Terrell Davis retired from football at 29 in 2001, and odds are his name didn’t enter your brain once until he made the Hall of Fame last year. He’s now 46. Not a single thing he’s done in 17 years has mattered to the popular culture.) We have pity for them at the end of their careers, because they remind us we are mortal, that we age and gray and crumble and die. No matter how little we could related to Brett Favre as a player, we can all relate to him in atrophy: We’re all decaying ourselves.

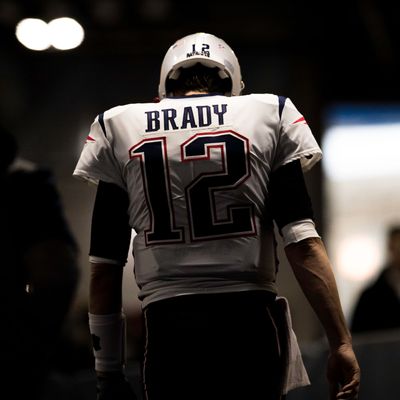

Which brings me to Tom Brady.

The New England Patriots are in trouble. They have lost two games in a row, one to the hated Steelers (a team they’ve typically dominated) and one to the Miami Dolphins in the most painful, improbable fashion imaginable. They’re likely to win the AFC East for the tenth consecutive season, but they’re likely a No. 3 or even a No. 4 seed in the AFC and have been passed by decidedly unglamorous teams like Kansas City and Houston in the conference. A team that has made three of the last four Super Bowls (winning two of them) and that has essentially dominated the NFL landscape for nearly two decades now (reaching eight Super Bowls and winning five), has fallen behind the pack. This is as bad as the Patriots have looked in December in years. The rest of football is smelling blood.

And perhaps most telling: Brady himself is looking old. He’s still efficient and smart, but he can’t really throw the long bomb anymore; he gets by on wiles and guile, both of which betrayed him at the end of the Steelers game, when he threw a reckless, very un-Brady-like interception deep in Pittsburgh territory. The reason Brady looks old, despite all the supposedly revolutionary (but mostly quackery) medical techniques employed by his shady trainer Alex Guerrero, is that he is old. Brady is 41 years old, which is older than Favre was when he retired, and in fact one of the oldest quarterbacks in NFL history. No quarterback at Brady’s age has ever seriously competed for a championship, let alone won one. As recently as last season, it seemed possible that Brady really was the cyborg his fans believed him to be, likely to last much longer as a productive NFL player than anyone ever had before. Now, he looks further from the Super Bowl than he has in a decade.

This is a problem for Brady, who, like all aging quarterbacks, wants to pull a John Elway and retire with one last title. (Peyton Manning also did this, but was so little a part of the Broncos’ title in his final year that he should probably only get half a ring.) It’s particularly key for Brady because of his persona as the ultimate winner, Don’t Count Out Touchdown Tom, there will be so much winning you’ll be tired of winning. If Tom Brady, who admits he can “see the end” of his career now, finishes his career without one final Super Bowl, it will be an ignominious end for a guy who, theoretically, could have retired after that amazing comeback against Atlanta two years ago and walked off the stage in the best possible way, rather than losing to Philadelphia last year and not making it this season.

But it’s a problem for us too, I’d argue. Because pitying Tom Brady just isn’t as satisfying as hating him, and hating Tom Brady — and his coach Bill Belichick — has been so much the central organizing principle of the NFL for 15 years that it is almost impossible to imagine the cultural future of the league without Brady and his Patriots as its eternal villain. It’s been quite a run — 15 of the most successful, riveting and, yes, controversial years of any league in any sport in professional sports history. The NFL may have outwardly celebrated Brady, but functionally it commodified Brady hatred, and turned it into an industry at large as any in the country; it has bled into the worlds of popular entertainment, meme culture, and of course national politics. Brady and Belichick, almost 20 years in, remain the most hated men in sports, by a large margin.

There is value in this: Sports hatred is the only socially acceptable form of public hatred, a way to get out aggression and frustration in a fashion that’s essentially harmless. (This is what watching sports is for: expressing big emotions that we can’t let out nearly as easily in our regular lives.) You and I might disagree on every major issue, and be total polar opposite human beings in every possible way, but we can come together in hating Tom Brady and Bill Belichick. I’ve quoted this before, but I’m reminded of Will Blythe’s old book To Hate Like This Is to Be Happy Forever, which was about hating Duke basketball but fits here perfectly. He quotes a 19th-century essay by William Hazlitt called “On the Pleasure of Hating:”

Nature seems made of antipathies. Without something to hate, we should lose the very spring of thought and action. … Pure good soon grows insipid, wants variety and spirit. Pain is a bittersweet, which never surfeits. Love turns, with a little indulgence, to indifference or disgust: Hatred alone is immortal.

The hatred of Brady and Belichick has been pure, and blinding, and, frankly, wonderful. But you can only hate something in sports if it is powerful: You cannot hate something that you pity. It is a lot more fun to jeer Tom Brady losing in the Super Bowl that it is to jeer him losing in the wild-card game. If the Super Bowl this year is Kansas City versus Los Angeles, it will be a terrific game between two exciting teams that the average fan will have no powerful emotions about one way or another. What fun is that? We want Brady and Belichick in that game. We want to see them suffer. Or we want to be angry when they win again.

But stars do not shine forever. Tom Brady, alas, is mortal, and in this mortality, I suspect, he will become more empathetic. Someday, maybe someday soon, he will retire, and he will go through the same process as Favre: neutered in his retirement, harmless in his irrelevance. We will have to find another villain then, because there always must be one. (It’ll probably be someone we like now: Remember, people were actually cheering for Brady and Belichick back in 2002.) The end of an athlete’s career is a sad spectacle, death in accelerated miniature. But losing Brady will have an extra poignancy: We’ll miss snarling at him as much as we’ll ever miss snarling at anyone.

So here’s hoping, alas, Brady has one last finishing kick left. Here’s hoping he can will his Patriots into one last Super Bowl, so he can have the grandest stage one last time, and we can all enjoy seeing him on that stage by calling him every horrible name we can think of. Because we’ll miss him when he’s gone. I sort of miss him already.