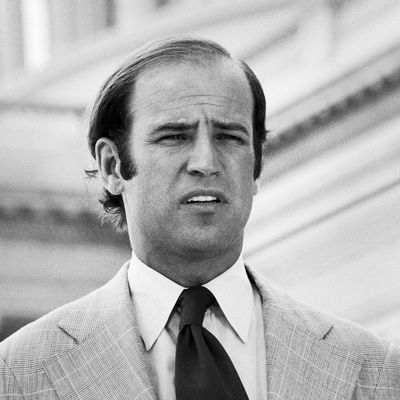

Former vice-president and senator Joe Biden has not yet decided whether to make a third bid for the presidency in 2020. But his relatively high standing in polls of Democrats, and his own conviction that he may be the only member of his party who can beat Donald Trump, are likely pulling him in that direction. The basic rationale for a Biden ’20 candidacy is that he can appeal to precisely those formerly Democratic voters Hillary Clinton lost to Trump in 2016, either because of his exceptional appeal to white working-class men, or simply because he is, unlike Clinton, a man.

Wherever they stand on the question of America’s readiness for a woman as president, self-consciously progressive Democrats have issues with Biden over his longtime identification with the centrist wing of their party. There are a couple of flash points in his background that you hear often from those who think he exemplifies a party tradition that needs to be firmly repudiated: his clumsy and insensitive handling of the Anita Hill–Clarence Thomas hearings in 1991, a memory rekindled this year by the similar confrontation between Christine Blasey Ford and Brett Kavanaugh; and his proud sponsorship of a 1994 crime bill that is now remembered as a key moment in the mass incarceration of nonviolent drug offenders and African-Americans generally. Both these grievances will be abundantly aired if Biden does move toward a candidacy.

But as Matt Yglesias argues today, these two especially sore points about Biden’s record are just the tip of the iceberg. And ideological issues aside, Biden’s record makes him the “Hillary Clinton of 2020,” not the candidate who can succeed precisely where HRC failed.

What brought Clinton down was public exposure not to her personality — which was sparkling enough to make her the most admired woman in America for 17 years straight before losing the claim to Michelle Obama in 2018 — but extended public scrutiny of every detail of a decades-long career in public life. This, in turn, is the exact same problem Biden will inevitably face as a presidential candidate. Americans like outsiders and fresh faces, not veteran insiders who bear the scars of every political controversy of the past two generations.

Yglesias notes a number of such controversies that may haunt Biden in 2020, beyond the two everyone talks about. There’s the Iraq War (which no other viable 2020 candidate supported), the 2005 bankruptcy bill (which brought a Harvard professor named Elizabeth Warren into the national spotlight on the opposite side of the legislation), the 1996 Defense of Marriage Act (now looked back upon as shameful by most Democrats), and even his “handsy” behavior around women.

Add it all up and you get a negative portrait of Joe Biden — the buckraker who failed to protect a sexual harassment victim and spent the aughts boosting the Iraq War and bank deregulation after fueling mass incarceration and anti-gay discrimination in the 1980s and ’90s.

But a deeper look suggests that Yglesias, too, is just skimming the surface of blasts from Biden’s past that could arise in a long, vicious campaign. Before he wrote the 1994 crime bill, he was heavily involved in three previous bills (in 1984, 1986, and 1988) that together constituted the bulk of the Reagan-era War on Drugs. And as Jamelle Bouie noted in 2015, Biden stuck with the tough-on-crime tradition even after it was obvious the collateral damage in ruined lives far outweighed the public benefit:

Biden would keep this approach, even as violent crime declined through the 1990s and into the 2000s. He would continue to vote for strong anti-drug efforts, going as far as to push for a federal crackdown on raves, citing ecstasy distribution. While Biden has shifted on some drug issues, he remains a staunch defender of his record on crime, even as Bill and Hillary Clinton have expressed their regret for the consequences of the 1994 crime bill and other anti-drug policies.

Joe Biden, in other words, is the Democratic face of the drug war.

That’s the sort of thing Biden must cope with as critics from both parties and the media conduct a more thorough exploration of his pre-1990s record. For one thing, he’ll again have to defend the infamous incident of speech plagiarism that destroyed his first presidential candidacy, in 1988. And that will in turn draw attention to a plagiarism incident from his law school days.

Going back even further, progressives can be expected to note Biden’s very visible involvement in the “anti-busing” furor of the 1970s, which threatened Democrats’ bonds with the civil-rights movement.

Now all of these questionable aspects of his record can be rationalized, particularly those that reflected evolving cultural attitudes and the very different Democratic political norms of past decades. But that’s a problem, too: Like Hillary Clinton, Biden is very vulnerable to becoming a caricature of the weaselly, endlessly prevaricating pol who bends with every passing breeze.

There’s no telling, moreover, what industrious oppo researchers might yet find in the man’s past. It’s hard to wrap one’s mind around Biden’s longevity in Washington. When he first came to the Senate in 1972, Spiro Agnew was the presiding officer of that chamber, and a small scandal dubbed “Watergate” was just getting serious attention. Bill and Hillary Clinton were still is law school, and had spent the previous summer campaigning in Texas for George McGovern. The Vietnam War was still raging, and “journalism” was still dominated by profitable newspapers and three television networks. It wasn’t just a different era — it was three or four eras ago.

The fellow late-septuagenarian Bernie Sanders has the same problem, which may have been obscured by the fact that the 2016 Clinton campaign chose to handle Bernie and his supporters with a relatively light touch (or as Bernie people might put it, with wire-pulling behind the scenes). Neither of them has dealt with the kind of vast Democratic field of rivals that is forming for 2020 — or with the kind of totally unprincipled and uninhibited attacks a Donald Trump reelection campaign can and will deploy (as Trump showed in 2016 with his treatment of Clinton, he is entirely capable of using intraparty critiques of Democratic candidates to undermine their campaigns). But between the two of them, it’s reasonably clear that Sanders and his history is more in accord with the prevailing winds in their party than is Biden.

The plumbing-to-come of Joe Biden’s distant and more recent past will, of course, turn up some moments that cast him in a much more positive or at least sympathetic light. No one can understand Biden without looking at the terrible tragedy (the sudden accidental death of a wife and daughter) that occurred before he took the oath of office as senator, and the ever-faithful father he became, a characteristic that he showed again during the recent illness and death of his son Beau. And he probably has a storehouse of testaments to his likable personality and his toughness under fire that could fill volumes.

But that’s the rub: Every examination of Biden’s life and record, positive or negative, will reinforce the public’s realization that he’s been in the highest levels of government for nearly a half-century. Aside from his advanced age and the risks that involves for his party, it’s not an enviable background in a country that doesn’t much trust career politicians. That could be the item of baggage among so many others than really drags down Joe Biden if he chooses to run for president.