In the middle of the George W. Bush administration, a large and persistent generation gap opened up in the American electorate. The full effects of this chasm have barely yet manifested — in part because young voters show up at the polls less reliably than old voters, and in part because the aging Republican coalition enjoys disproportionate representation in the House, Senate, and Electoral College. But one of the ways it will change American politics is that it will eventually render abstract appeals to small-government conservatism obsolete.

The Pew Research Center has a new survey identifying generational changes in the electorate. It finds “post-millennial” voters, those born after 1996, having views just as liberal as millennials. That is to say, the shift to the left among younger voters is not a bubble or a transient response to formative events (like George W. Bush, Barack Obama, or the financial crisis) but a durable change. And, as Republican pollster Kristen Soltis Anderson has warned her party, the notion that young people normally start out liberal and move to the right is a myth.

What’s more, while the generational shift has often been framed in ethnic terms, increasing diversity is not the GOP’s only problem. Young white voters have more liberal views on social policy and the role of government than older white voters. It is not just that there are too few white voters to sustain the current Republican coalition, but that the white voters aren’t conservative enough.

One familiar question on the survey asks respondents if the government should do more to solve problems or if it is already doing too many things better left to businesses and individuals. Throughout most of the last quarter century, a majority of the public has said government is already doing too much:

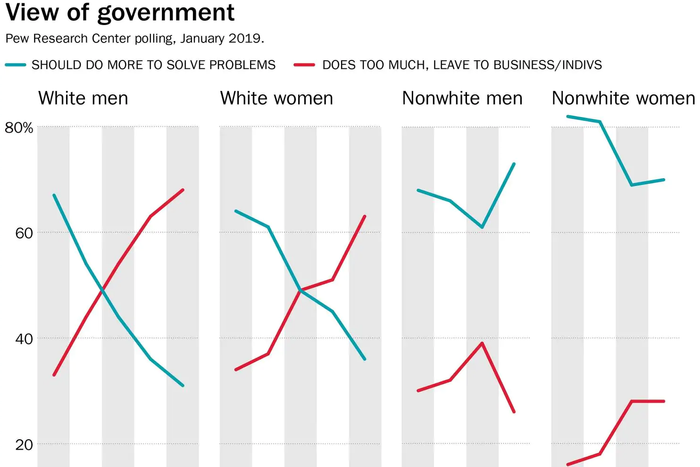

Philip Bump broke out several of the responses in this survey by race, gender, and age. Look at the generational change among whites on this question:

Since about 1966, when Republicans rode a backlash against the Great Society and a wave of urban riots to a large midterm victory, America — especially white America — has viewed government with suspicion. That suspicion has not always or even usually translated to specific government programs. Most of what government does has remained popular. Nevertheless, the general idea that government wastes money promiscuously, and the specific belief that it gives money to undeserving minorities, has given Republicans a powerful weapon.

Attacking big government in the abstract has been the default Republican argument on domestic policy for half a century. The theme was sounded in Richard Nixon’s 1968 presidential acceptance speech: “For the past five years we have been deluged by government programs for the unemployed, programs for the cities, programs for the poor, and we have reaped from these programs an ugly harvest of frustrations, violence, and failure across the land. And now our opponents will be offering more of the same — more billions for government jobs, government housing, government welfare.”

And in Ronald Reagan’s 1980 acceptance speech: “I believe it is clear our federal government is overgrown and overweight. Indeed, it is time for our government to go on a diet … I will not accept the excuse that the federal government has grown so big and powerful that it is beyond the control of any president, any administration, or Congress.”

And George W. Bush’s 2004 speech (referring to his opponent): “His policies of tax and spend, of expanding government rather than expanding opportunity, are the politics of the past.”

And John McCain’s in 2008 (referring to Obama): “I will cut government spending. He will increase it … His plan will force small businesses to cut jobs, reduce wages, and force families into a government-run health-care system where a bureaucrat stands between you and your doctor … Reducing government spending and getting rid of failed programs will let you keep more of your own money to save, spend, and invest as you see fit.”

Republicans did not always win these arguments, but they grasped the strategic imperative. Democrats wanted to debate specific programs with specific effects. Republicans wanted to debate government as an abstraction. The debate carried a deep racial subtext. White people thought the government was doing too much, and nonwhites thought it needed to do more.

Those two large X’s on the left side of the chart show the rapid generational disintegration of anti-government conservatism. They reveal the degree to which young white voters have views of government almost as supportive as nonwhite voters. Older whites think, by about a two-to-one margin, that government is doing too much. Younger whites, by about a two-to-one margin, believe the opposite.

At some point in the not too distant future, the tension between the public’s symbolic conservatism and its operational liberalism will become less relevant, if not completely moot. The implications of this change will be profound. Republicans have spent years relying on the argument that big government is inherently bad. At some point, they will need a new philosophy.