Up until now, the longest government shutdown in U.S. history was the 21-day standoff between President Bill Clinton and a Republican Congress led by Speaker Newt Gingrich that ran from December 16, 1995, to January 6, 1996. It revolved around big, consequential differences in policy views about the size, cost and priorities of the federal government, and produced a backlash to the Republican Revolution of 1994, ultimately resulting in Clinton’s fairly easy 1996 reelection. Plenty of people, including furloughed government employees, were unhappy about the shutdown. But nobody much called it “stupid,” other than those who interpreted Gingrich’s stubbornness to pique over being dissed by Clinton during a trip on Air Force One.

The current shutdown, which will break the record for longevity this weekend, is obviously about much narrower issues, and is by all accounts pretty “stupid” insofar as it wouldn’t have even happened had President Trump not panicked over right-wing gabber criticism of his willingness to keep the government open without the border wall funding he had been demanding. But Congress has given up for the time being on trying to cut a deal to end the shutdown, as the Washington Post reports:

The House broke for the weekend Friday, all but ensuring that the partial government shutdown would become the longest in U.S. history, while President Trump continued his efforts to sway public opinion on the need for a U.S.-Mexico border wall.

As of early Friday afternoon, there were no signs of serious negotiations underway, and leaders of both chambers announced no plans to meet before Monday.

The Democratic-controlled House has been busy passing appropriations bill to reopen various shuttered portions of the federal government which the Republican-controlled Senate has is refusing to take up. Both chambers did pass contingent legislation providing (as expected) that furloughed federal employees would eventually get back pay once the government reopens (a timely measure since such employees and those being required to work without pay just missed their first paychecks today), which Trump has said he’d sign.

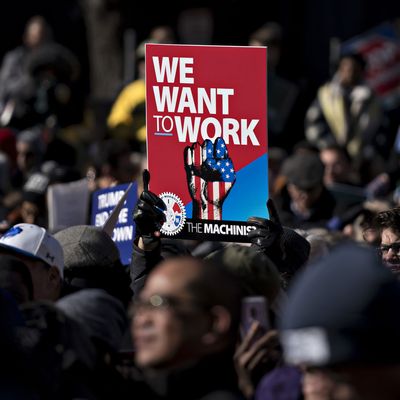

Of the two most prominently discussed avenues for resolving the shutdown, one seems to be dead and the other is in limbo. The dead-end was some sort of big deal (Senator Lindsey Graham was the most notable proponent, with assistance from presidential son-in-law Jared Kushner) trading border wall funding for relief for Dreamers and perhaps migrants whose refugee status has been threatened by the administration. But Trump flatly rejected the whole construct, preferring to keep the DACA program for Dreamers on ice until such time as the Supreme Court reviews his stalled planned to end it. And Democrats were less than jazzed about the idea as well, particularly given significant progressive pressure to hang tough on the wall:

The other way around the shutdown that’s been under active discussion is one that would take the whole border wall issue out of the hands of Congress: a national emergency declaration by Trump followed by presidential action to redirect existing funds, probably from the Department of Defense. That option has been greeted with relief by some in both the White House and Republican congressional circles as a face-saving way in which Trump can at least claim he’s building his border wall while allowing the federal government to reopen.

But there are growing expressions of concern in GOP circles about the precedent this step would set. It isn’t a good sign that some of these critics are members of the House Freedom Caucus, probably Trump’s staunchest allies in Congress. And though the law of emergency declarations is murky and unsettled, there are also serious reasons for Republicans to worry about how the courts might handle a declaration. A quick injunction against his power to make the declaration, particularly if it occurs immediately after the federal government has reopened, could really make Trump look like a loser. Since his ego (and his ever-demanding “base”) is largely driving this whole saga, that would be intolerable to him.

At this point the big question is whether the White House will plunge into a potential legal and political quagmire over an emergency declaration, or carefully plot a plan even as the pain of the government shutdown intensifies and his allies grow more restive. The president’s latest signals are not exactly clear:

Looks like he needs to cut a deal with himself.