To hear him tell it, Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu isn’t sweating the multiple bribery and corruption investigations in which he may soon be charged by the country’s attorney general Avichai Mandelblit: The investigators will find nothing against him, he has repeatedly contended, because there is nothing to find.

Judging by his actions, however, he’s clearly worried about it. On Monday afternoon, the prime minister announced on Twitter that he would make a special address to the nation at the start of the evening news hour, leading to a flurry of speculation: Was he about to resign? Mount some kind of legal challenge to prevent the attorney general from issuing indictments before the upcoming national elections? Declare a national emergency, perhaps?

None of the above, as it turns out. In his seven-minute prime-time address, Netanyahu instead served up a nothingburger of gripes and demands he has already made repeatedly. He accused his enemies on the left and in the media of pursuing a witch hunt against him (not unlike President Trump) and restated his talking point that it would be undemocratic for Mandelblit to accept the recommendations of the police and charge him in these cases, which the attorney general is widely expected to do in February, before the April 9 elections. This would not leave enough time for him to defend himself in pre-indictment hearings before voters went to the polls, he argued.

The only new information Netanyahu revealed on Monday night was that he had demanded to confront the former colleagues and aides who had turned state’s evidence against him, but had been denied that opportunity by the legal authorities (such confrontations are not standard procedure in the Israeli justice system). He issued this demand again, saying he wanted to confront the state’s witnesses face-to-face on live TV: “What are they afraid of? What do they have to hide?” he exclaimed. “As far as I am concerned it can be broadcast live, so the public can see and hear it.”

The speech was so blatantly self-serving and unnewsworthy, Israel’s Channel 10 cut off its broadcast in the middle of it. “Editors were sitting in the control room, and once they decided there was no news they cut the live broadcast,” the station’s chief political correspondent Barak Ravid said afterward.

Other journalists and commentators were similarly dismissive of what had been hyped as a “dramatic announcement.” The Times of Israel’s David Horovitz described it as “not so much misguided as irrelevant,” as it was unlikely to influence Mandelblit’s decision and unnecessary to sway voters in an election Netanyahu is already heavily favored to win. Horovitz’s colleague Raphael Ahern called it a “dangerous gamble,” remarking: “The next time the prime minister-who-cried-wolf wants to address the nation to announce a mysterious matter of purported national urgency, fewer people may pay attention.”

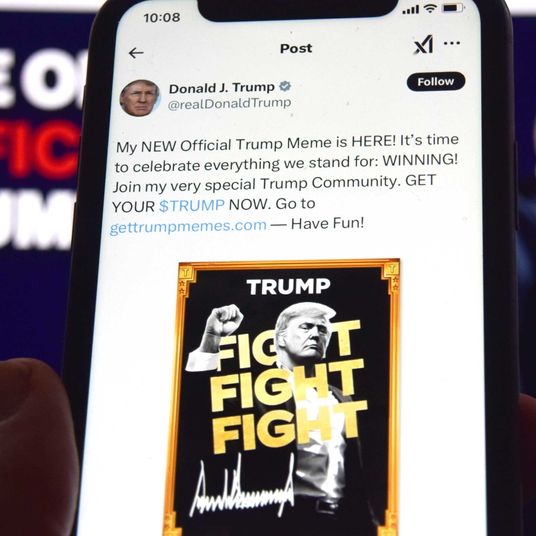

It was the second time in as many months that Netanyahu had used a TV broadcast, which Horovitz notes is “a channel of direct communication usually reserved for events of momentous national import,” to serve his own political needs: In November, he gave a nine-minute address as part of a media blitz to head off a challenge from his coalition’s right flank. If Trump discovers tonight that he likes using this medium to fight his political battles, we might start seeing something very similar here in the U.S. (Both men already share a love of using Twitter to build narratives.)

The crimes for which Netanyahu is expected to face charges are serious. In Case 1000, he is suspected of taking more than $250,000 worth of benefits and gifts from billionaire cronies. Case 2000 and Case 4000 include allegations of illicit deals between Netanyahu and the owners and publishers of media companies to trade regulatory decisions that either helped them or hurt their rivals for favorable coverage in their outlets. Police have recommended charging the prime minister with bribery in all three cases.

With political pressures bearing down on him from all sides, the Washington Post’s Jerusalem bureau observed on Sunday, Mandelblit is in a lose-lose situation not unlike the one former FBI director James Comey faced in October 2016, when he had to decide whether to announce that the bureau had turned up new evidence in the investigation into Hillary Clinton’s emails. That evidence quickly came to nothing, but Comey’s revelation of it in the lead-up to the presidential election likely helped tip the race against Clinton and toward Trump. If Mandelblit decides to indict Netanyahu, the prime minister’s Likud party will accuse him of improperly influencing the election. If he holds off, he will be accused of denying Israelis important information that should influence their vote.

Netanyahu knew all this when he called early elections last month in the wake of his coalition’s collapse. Indeed, Monday’s address was surely intended to turn up the heat on Mandelblit and raise the political stakes of his decision further, even though it mostly rehashed grievances he had already aired. Opinion polls find that most Israelis believe the attorney general should issue a decision before the election, but other polls show it wouldn’t cost Likud any seats in the Knesset if he were to face charges. Netanyahu has insisted that he will refuse step down if he is summoned for an indictment hearing, which he is not required by law to do, though a slim majority of Israelis said in a recent poll that he should.

The prime minister and some of his supporters have reacted to the corruption allegations in troubling ways, with former Supreme Court justice Eliyahu Matza likening Netanyahu’s rhetoric to that of a mob boss (another Trump parallel) and calling it “nothing less than incitement against the attorney general and law enforcement authorities.” When a leading Likud MK tweeted that millions of Israelis would “not accept” an indictment, the state prosecutor described the tweet as “super-problematic.” Mandelblit has been targeted personally: His father’s grave was vandalized in December, and graffiti recently appeared on a highway sound barrier labeling him a “collaborator.”

Again, however, Likud remains the favorite to lead a government once again after April’s elections. While Netanyahu’s popularity has taken a hit amid these allegations and political turmoil over the past few months, his party only needs to win a quarter of the vote and more seats than any other party to rule, which the polls say is almost certain.

Beyond Likud, Israeli party politics is severely fractured at the moment, which works to the ruling party’s advantage. The center-left opposition is deep in the wilderness, politicians and retired generals are leading brand-new parties, and Netanyahu’s main threat on the right fragmented last week when ultranationalists Naftali Bennett and Ayelet Shaked abandoned their pro-settlement party Jewish Home and formed a new party called the New Right. Netanyahu knows that as long as right-wingers win at least 61 out of 120 seats, he can cobble together a coalition that keeps him and his party in power.

He’s not completely out of the woods, of course, but even if Netanyahu falls, the increasingly hawkish and zealously nationalist Israeli right is likely to remain in power for years to come. Israel’s continuous rightward drift, combined with the policies Netanyahu has pursued in his last three administrations, suggests that April’s elections will effectively serve as a referendum on whether to abandon the two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and pursue the annexation of the occupied territories instead — and that referendum will likely win.

Unfortunately, it’s being portrayed instead as a referendum on Netanyahu himself, as the larger-than-life leader’s legal troubles draw valuable attention from the critical questions of national identity, social and economic stratification, security, and foreign policy Israel will actually need to answer in the years to come. Sound familiar?