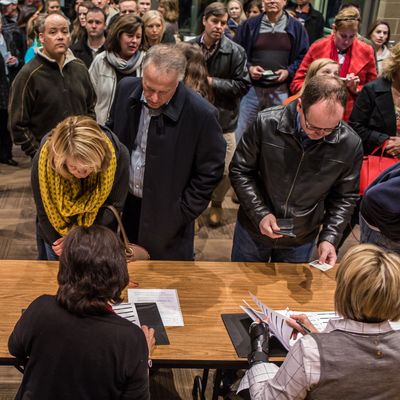

From the beginning of the modern era of popular control of the presidential nominating process (basically inaugurated in 1972) to very recently, the unrepresentative nature of the first two stops on the road to the presidency, the first-in-the-nation Iowa caucuses and the first-in-the-nation New Hampshire primary, was a chronic complaint. This was especially true for an increasingly diverse Democratic Party that nonetheless gave two small and very white states (as of the 2000 census, Iowa was 94 percent white and New Hampshire was 96 percent white) protected status as dominant factors in the nominating process.

After the 2004 cycle, Democrats (followed eventually by Republicans) got serious about this problem, and introduced calendar reforms that added two more diverse states — Latino-heavy Nevada and African-American–heavy South Carolina — to the early mix. Super-honkified Iowa and New Hampshire still got to go first, but nonwhite voters got to have a say before the whole deal was done. Indeed, Barack Obama’s successful nomination strategy combined an Iowa win with a dominant performance in southern states with large African-American voting populations, beginning with South Carolina. Hillary Clinton followed the same pattern in overcoming a terrible New Hampshire performance in 2016 by wins over Bernie Sanders in Nevada and South Carolina that put her ahead for good.

The 2020 nominating contest will represent a big leap forward in the development of a more diverse early calendar for Democrats, as Ron Brownstein explains:

As in every recent Democrat primary race, the 2020 contest will begin in two virtually all-white states, with the Iowa caucus and New Hampshire primary in early February. But after that the next month of the primary calendar is dominated by states across the Sun Belt where non-white voters comprise a large share, and often an absolute majority, of the electorate.

This decisive turn toward diversity, reinforced by California’s decision to move up its primary to Super Tuesday, represents a potentially critical new wrinkle in the nomination process. The pivot begins with Nevada and South Carolina, where contests will be held in the second half of February. The tilt toward diversity then explodes in early March when big Sun Belt states from Florida, North Carolina and Virginia in the southeast to Arizona and Texas along with California across the southwest will all crowd together on the calendar.

This shift may actually be intensified by the fact that while Iowa and New Hampshire have never embraced early voting, their new competitors emphatically have, as my colleague Gabriel Debenedetti has pointed out:

[S]trategists aligned with potential contenders’ teams are already starting to plan for 2020 by operating under the assumption that early voting in California — the state with the most delegates up for grabs — will start the very morning of Iowa’s evening caucuses, the traditional kickoff. (Vermont’s primary voting will have already begun by that point, if the current expected schedule holds.)

Usually, all the attention then shifts to New Hampshire directly after Iowa. This time, though, Ohio and Illinois could both begin their own early voting before the Granite State’s day in the spotlight, and Georgia and North Carolina could start the day of New Hampshire’s primary. Then the windows could open in Tennessee, Texas, Arizona, and Louisiana before Nevada’s caucuses, let alone South Carolina’s primary.

All these wrinkles are likely to reinforce nonwhite voting power, notes Brownstein:

Through March 17, the Democratic candidates will face significant Latino populations in Texas and California on Super Tuesday and then Florida and Arizona on March 17 …

Starting on Super Tuesday [March 3], large black populations will vote through mid-March in Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Alabama, Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Florida and Illinois. In all of these states, minorities comprised at least about two-fifths of the 2018 vote, and they reached majority status in several of them, including Alabama, Mississippi, Florida and Texas. Given the overall trends in the party, Democratic strategists consider it likely that the nonwhite share of the vote in virtually all of these states will be higher in 2020 than it was in 2016.

If that’s not enough diversity, New York may move its primary to March as well.

These dynamics will likely help candidates who really do well among nonwhite voters while hurting those who don’t. It could, as in 2008, put a minority candidate in the driver’s seat, though the fact that there are at this point a Latino (Julian Castro) and two African-American (Cory Booker and Kamala Harris) candidates could keep the nonwhite vote split up for a good while.

It’s even possible that candidates will be tempted to skip or skimp on Iowa and New Hampshire as outlier states. But the fact remains that the only candidate since 1976 to win a presidential nomination in either party while losing both Iowa and New Hampshire was Bill Clinton in 1992, who was running against a relatively small and weak field at a time when Iowa was taken off the table by favorite son Tom Harkin.

So the former longtime duopoly of Iowa and New Hampshire will still matter in 2020. But they’d do well to elevate candidates who are prepared to excel in the next very difference phase of the nominating process. Indeed, with a good opening push from the very white electorate of these two states, a candidate with strong minority voting appeal could wrap things up relatively early despite the vast field of rivals she or he will face.