City Hall’s sweeping ThriveNYC mental-health program has been losing behavioral health workers in droves from its largest program, according to figures obtained by THE CITY.

The Mental Health Service Corps — which accounts for nearly 20 percent of ThriveNYC’s $250 million annual budget — launched in mid-2016 to place novice psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers in high-need communities for three-year commitments.

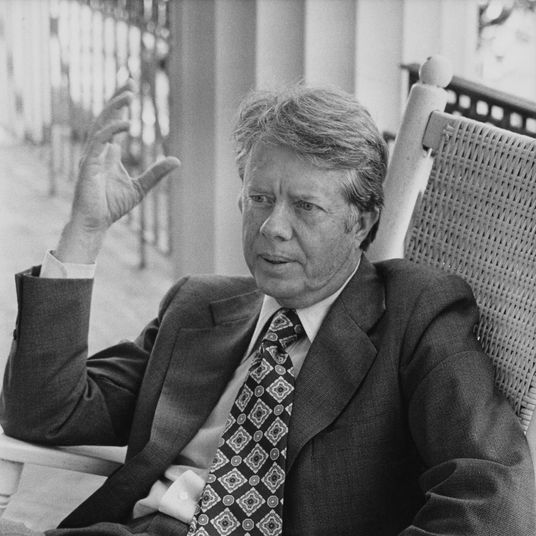

“With our Mental Health Service Corps we are mobilizing our mental health professionals to help make New York City a place where it is as easy to get help for anxiety as it is for allergies,” First Lady Chirlane McCray said in a statement announcing the first class of clinicians, asserting herself as a driving force behind the 42-program Thrive initiative.

But of the first cohort of 125 staffers placed by the program later that year, 79 — or 63 percent — have since left their assignments.

Nearly 30 percent of a second cohort of 129 workers hired in 2017 quit before reaching the two-year mark.

The Mental Health Service Corps currently has 263 clinicians, short of its initial goal of placing as many as 400 within primary-care practices.

The preliminary budget released last month by Mayor Bill de Blasio cuts the budget for the Mental Health Service Corps by $1.9 million for the coming fiscal year that begins July 1, down from $47.5 million in the current year.

The proposed annual budget decline will nearly double to $3.7 million the following year.

In an annual report to the state last July, the city’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene stated that the service corps “has had difficulty recruiting and retaining a diverse behavioral health workforce” — including clinicians who speak a language other than English.

Low Pay and High Demand Hasten Exits

City Hall officials cited travel hardships to locations outside of Manhattan, lack of provider readiness, and clinicians who are poached from the program by other employers among the reasons for the retention challenges.

Recently graduated social workers and mental-health counselors in the program start at $55,000 a year, they added, while psychologists start at $60,000.

The staffing difficulties have prevented some community organizations from participating in the Mental Health Service Corps program.

“The clinic was not able to benefit from the New York City Mental Health Corps because initially they didn’t have a Korean-speaking clinician,” Joanne Park, clinic director at the Korean Community Services of Metropolitan New York in Queens, testified last week at a City Council hearing on ThriveNYC. “And then the solution that was offered was [for us] to get a translator — which of course is not appropriate in a mental-health setting.”

She later told THE CITY the program has “so much potential” and “there’s certainly a need for it.”

While the preliminary budget adds funding for ThriveNYC services at job centers, senior centers and private office buildings, two other programs face elimination.

The Mental Health Innovation Lab, a data-analysis center, and Thrive Learning Center — an online library of information and guidance for staff at community partner organizations — will be shuttered, saving $2.2 million per year.

City Hall officials said the data lab “failed to meet deliverables,” while the $600,000-a-year learning center drew an average of just 58 visitors per day.

The cuts were quietly tucked into budget documents just as ThriveNYC began to attract increased scrutiny over its $250 million annual budget, along with growing concerns over a lack of transparency and quantifiable results.

ThriveNYC reports statistics that focus on inputs rather than outcomes — such as its NYC Well hotline, which has fielded 567,000 calls, texts and chats since fall 2016, and 100,000 New Yorkers trained in Mental Health First Aid.

Questions Over Spending and Results

At the Council hearing, Brooklyn council member Alicka Ampry-Samuel — who noted she once worked in social services — said she’s never seen so many homeless people with mental-health issues.

“What I’m noticing now is I see more mentally ill homeless people in the street and in the subways than I did when I was actually working directly in the field,” she said. “It’s just baffling that here it is we’re spending $250 million … but we’re seeing so many more people [needing help] every day.”

At the same hearing, advocates for students with mental-health issues and adults in the criminal-justice system testified that the Mental Health Service Corps is well-intended, but that high-need clients haven’t gotten better access to services since the launch.

Jason Lippman, vice-president of the Coalition for Behavioral Health — an umbrella group of more than 100 nonprofit behavioral health agencies — said the Mental Health Service Corps hiccups aren’t unique to ThriveNYC.

His group was among a statewide coalition that found a 42 percent turnover rate and a 20 percent vacancy rate among behavioral-health providers in New York City in 2017, in part because of low wages.

“That is pretty significant,” he testified.

Last Friday, Comptroller Scott Stringer wrote a letter to City Hall seeking an accounting, by March 14, of the program’s spending and impact to date — a call echoed by other elected officials.

The sudden scrutiny has spurred considerable pushback from City Hall, but it’s also yielded greater transparency.

This week, officials provided the most detailed accounting yet of ThriveNYC’s spending since the program began, and project $565 million in expenditures by the end of June.

The chart shows that a number of prominent programs — including a $6.2 million allocation to provide mental-health services at 50 schools, and $9.5 million to operate new diversion centers for people who’ve interacted with law enforcement — have been slow to get off the ground.

For at least two years, not a dime of funding for either program was spent.

When asked about the overall outcomes Wednesday, McCray said recent demands for demonstrable results aren’t realistic given the challenges of measuring health benefits — a process than can take years.

“People like immediate success,” she said at an event at the Brooklyn Museum of Art.

“We have more than 400 metrics, a robust, rigorous program that is completely transparent.

“You can’t track everything right away,” she added. “The kinds of measures you’re thinking about, we’re not really going to have them for awhile.”

Have you ever worked for or with the ThriveNYC Mental Health Service Corps? We want to hear about your experience. THE CITY will not use or disclose any of your information without your express permission. Email: [email protected]

Don’t miss out on the next big story. Sign up for THE CITY’s newsletter here.