Everywhere Hakeem Jeffries travels, the prospect of his next job in politics precedes him like a rhetorical red carpet, unfurled for the four-term congressman to walk upon should he choose to.

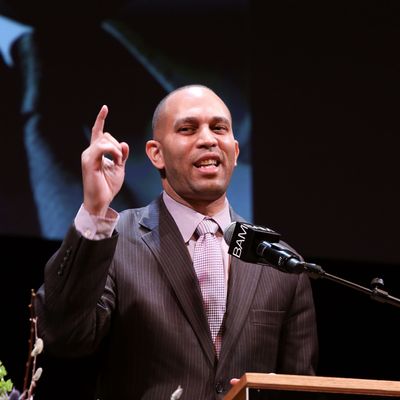

On Martin Luther King Day, as Jeffries zooms around New York City from small church service to political rally to evening Scripture reading, that next step is sometimes explicit — “We don’t want to get too much ahead of ourselves but you are looking at future Speaker of the House of Representatives,” City Council Speaker Corey Johnson tells the morning crowd at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, where Jeffries is hosting a King celebration — but more often than not, a yellow brick road leading to a gestured at but unnamed Political Oz.

“The sky is the limit for Hakeem Jeffries,” said Joe Crowley, the former Queens congressman whose upset loss last summer paved the way for Jeffries to take his spot in the House leadership. “He can reach the highest heights in our caucus and I think it would be great for New York as well to have a Speaker. It’s been a long time.”

“He is beyond a rising star, he is like a supernova in the universe right now,” Laurie Cumbo, a city councilmember from Jeffries’s home base of central Brooklyn, told the crowd at the same event.

For his part, Jeffries, who is currently the fifth-highest ranking member of the Democratic leadership in the House, never says a word when a dozen will do. He pauses before he speaks, and then delivers a perfect paragraph, one that touches on all of the party’s talking points, and then stops when he reaches the end, and can sit through the longest of awkward silences without starting again. Even friends and congressional colleagues find it uncanny.

Democrats in 2018 didn’t ignore Trump, he says, they “developed a process to resist the notion that we have to chase the after the shiny objects he holds out in front of the American people as bait for Democrats to react and to distract from the issues that Americans care about most.”

Congressional Democrats in 2020 won’t be focusing on battleground districts, he says, but “there are targets of opportunity that may develop over the next two years, and with regards to those targets of opportunity, because we were so successful in winning more seats than any midterm election since Watergate, we have to protect our frontline members who the Republicans will be targeting, and so we will have to be like Willie Mays, who played both great offense and great defense.”

And so, over a late lunch of grilled fish, steamed vegetables, and green tea at Junior’s in Brooklyn, Jeffries predictably demurs when asked if he has his heart set on the Speaker’s gavel.

“My sole focus is to make sure the House Democratic Caucus is successful in delivering on our political agenda and helping our eventual Democratic presidential nominee be successful in 2020. In my view, you do the current job you have, you do it well, and the future will take care of itself. We have a lot on the agenda and the last thing we should be doing is thinking about future ambitions for this, that, or the other office.”

As my eyes rolled, he continued: “I enjoy the job that I have. It is a great privilege to be able to represent the Eighth Congressional District of Brooklyn and Queens. We will see what the future holds. ”

Jeffries’s rise has been both steady and nothing short of remarkable. His grandfather moved to New Jersey as a child after his own father, a mason down in Georgia, was lynched by the Klan. Jeffries’s grandfather was a tailor in New York. His father, Marland Jeffries, moved to New York and got a job as a caseworker with the city’s Department of Social Services. His mother, Laneda, was a social worker. Jeffries grew up in Crown Heights in the 1980s. His parents still live in the neighborhood, as does he. Wondering whether or not the sounds outside the house were gunshots or firecrackers was a childhood pastime. His mother, he says, got mugged repeatedly, and his father took up martial arts. Marland Jeffries ran for the State Assembly in 1978 as part of a group of black nationalists challenging the Brooklyn Democratic machine. He got kicked off the ballot. (Jeffries’s uncle, Leonard Jeffries, is a former professor at the City University of New York who was removed from his position for incendiary comments about whites and Jews.)

Jeffries went to SUNY-Binghamton, got his law degree from New York University School of Law, and received a master of public policy degree from Georgetown, where he roomed with future Washington mayor Adrian Fenty.

After Georgetown, Jeffries landed at the white-shoe law firm Paul, Weiss and spotted an opening in the State Assembly where Roger Green, a longtime lawmaker and civil-rights activist, was seen as out of step with a changing district. Jeffries, then just 30, went door-to-door in the district, and grabbed a surprising 40 percent of the vote. The next year, the Assembly Democrats redrew district lines after the census, and drew Jeffries’s home one block outside district lines. (“Brooklyn politics can be pretty rough,” Jeffries said in a 2010 documentary about gerrymandering. “But that move was gangsta.”) In 2002, Jeffries bought a home in the new district and moved his young family in, and eventually won the seat. He was immediately pegged as a rising star, someone who could nearly clear the field if he ever decided to run for mayor, but he decided instead to run for Congress against Ed Towns. Like Green, faced with the prospect of a campaign against Jeffries, Towns decided to retire.

His ascent in Congress was equally quick. After just two terms, in the wake of the Democrats’ staggering defeat in the 2016 election, Jeffries was named co-chairman of the Democratic Policy and Communications Committee, charged with communicating the party’s priorities to the wider public.

It is easy to see why. As careful as Jeffries is in conversation, he is equally caustic on the stump. After Trump told a rally crowd in Cleveland that Democrats were “treasonous” for not clapping during the State of the Union, Jeffries took to the floor of the House with a sign that said in big red letters, “Treason?”

“How dare you lecture us about treason?” Jeffries proclaimed, noting that a truer definition of treason would be meeting with Russian intelligence to rig the 2016 election. “This is not a dictatorship, it is a democracy and we do not have to stand for a reality-show host masquerading as president of the United States.”

Jeffries has often been compared to Obama, but if Obama’s mere presence stood for racial reconciliation, and if Cory Booker, another figure to whom Jeffries has been compared, stands for the healing power of love, Jeffries is more interested in calling out bullshit when he sees it.

“These are strange times in Washington,” Jeffries told one crowd on Martin Luther Jr. Day. “We have a hater in the White House, the birther-in-chief, the Grand Wizard of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. One thing we have learned is that while Jim Crow may be dead, he has still got some nieces and nephews that are alive and well.”

They aren’t gaffes; Jeffries is incapable of making those. Asked whether it is really elevating the discourse to call the president of the United States the Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, the congressman shrugs. “It is unfortunate that someone with the tendency to act like a racial arsonist now finds himself as president of the United States of America, who should be trying to bring us together instead of tearing us apart. ”

If such language shocks the delicate sensibilities of the pundit class (it doesn’t really — Jeffries remains a favorite of cable news bookers) or leads to reprimands from parliamentarians on the House floor (as has been known to happen), it causes Jeffries no trouble at home.

“He feels his district,” said Cedric Grant, his former chief of staff. “When he talks about President Trump, he is saying the things they would say and feel. It may be a shock to some, but it reflects his constituency back home.”

Jeffries got his position in the leadership when Joe Crowley, the two-decade incumbent congressman from Queens, lost in a shocking upset to Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. Crowley lost in part because he had moved his family down to the Washington suburbs and was more focused on replacing Nancy Pelosi as Speaker than he was to the concerns of his district. Jeffries still lives in the neighborhood where he grew up with his wife, a social worker, and his two teenage sons, both of whom attend public school in the area. And although it can be jarring — Jeffries does after all have a law degree and is over a decade into a political career — he drops hip-hop references with ease, paying tribute to Notorious B.I.G. on the floor of the House and nominating Pelosi for another term as Speaker by declaring that “House Democrats are down with N.D.P. — Nancy D’Alesandro Pelosi,” flourishes intended to remind his constituents back in Brooklyn that he hasn’t forgotten them.

But since Democrats won control of the House in November, Jeffries’s uninterrupted rise has at last run into turbulence. In December, Politico ran a story soon after his ascension to the House leadership, that allies of Ocasio-Cortez were preparing to challenge Jeffries, arguing that he was too much of a centrist, especially after he had beaten Barbara Lee — a 72-year-old member of Congress from the East Bay beloved by liberals, in part for being the only lawmaker to vote against the war in Afghanistan — for his post as caucus chair. In print, Jeffries shrugged off the story, quoting Notorious B.I.G. again: “Spread love, it’s the Brooklyn way.”

Ocasio-Cortez ultimately denied that she was targeting her fellow New Yorker, but the story clearly bothered Jeffries. “Mr. Jeffries is nearly as moderate as a safe seat Democrat gets,” proclaimed The Economist before the election, touting his support of charter schools, his relative hawkishness on foreign policy, especially around the Middle East (his district is one of the most Jewish in the country), and his friendliness with the party’s pro-business wing.

Jeffries doesn’t shirk from the label, but also touts his A rating from the ACLU, NAACP, and the League of Conservation Voters. “Mathematically I am one of the 25 most progressive members of the United States Congress. There were some in the aftermath of the competitive leadership race that [suggested] I was a big-money centrist. It was a strange accusation to make. I would hear it and I would look around and ask, ‘Are they talking about me? Where are you deriving this conclusion from?’ I plead guilty to the fact that I am not as progressive as Barbara Lee but neither are 435 other members of the House of Representatives.”

Jeffries can’t complain much about primaries; challenging Democratic incumbents brought him to both the Assembly and to Congress. Ocasio-Cortez did not deny the story when it ran, but later did so on Twitter when pressed. Jeffries said that she had not brought it up to him personally to say that it was not true.

“She is a dynamic new member of Congress and has a lot to contribute, but so do this wonderful freshman class as a collective entity. My view is I want everyone to be successful, including Alexandria, but without losing focus on many of the members who were elected from tough districts who need to be successful if we are going to keep our majority,” he said. “With respect to Alexandria, we have participated in New York delegation meetings together, we are very cordial with each other, and I wish her nothing but the best.”

Any primary challenge against him would be hard. As central Brooklyn has changed, Jeffries has benefited. The white gentrifiers who have moved in in droves for the past two decades see him as one of them: a striver with the proper pedigree, and a corporate lawyer with a burning hatred of Donald Trump. He remains a member of the Cornerstone Baptist Church where he grew up, is a favorite of the pastors in the community, and works the district relentlessly.

“I don’t think you can underestimate the power of someone who gets on both MSNBC three days a week and shows up at church on Sundays. It’s a full-frontal assault,” said one Jeffries friend. “Any primary challenge would look a lot like Barron” — with is to say an easy win by Jeffries. “There is a ceiling.”

More worrisome for Jeffries and his likely ascension to the Speaker’s chair is that he barely eked out a victory over Lee. Jeffries is supposed to be the future of the party at a time when the question of who will replace the current leadership of Pelosi and her allies is tantamount. Jeffries ended up winning by only ten votes, and when you figure it’s likely that none of the moderate factions of the caucus, like the New Democrats or the Blue Dogs voted for Lee, and that almost all of New York — besides Ocasio-Cortez — were behind Jeffries in the secret ballot, it means that she must have won nearly all of the other votes that were up for grabs. According to some reports, it was only arm-twisting from some members of the House leadership that brought Jeffries over the edge.

“If you want to move up the ranks, you can’t just have charisma,” said one senior House aide. “You have to put in the time, you have to have the skills to convince people to work on your behalf, and you have to have a vote-counting operation. Half of our caucus thought that Barbara Lee was the future of our party? That says a lot about his deficiencies.”

Jeffries was mentioned as a potential Speaker even before the 2018 election, back when there remained consternation in the Democratic ranks that Nancy Pelosi would spell certain electoral defeat. His team worked hard to tamp down the speculation, and Jeffries has remained a loyal lieutenant. His advisers acknowledge that the prospect of a Speaker from New York would be difficult as long as the Senate Majority Leader is New Yorker Chuck Schumer.

Still, it’s hard to see anything that would slow Jeffries’s rise.

Later on MLK Day, Jeffries stopped by the National Action Network headquarters in Harlem. There, Al Sharpton introduced him. “Giants stand on the ground and reach new heights. He has grown to be a giant but he is grounded.”

Jeffries led the crowd in a “No Justice! No Peace!” chant, repeated his claim that there was a Grand Wizard in the White House and told two stories. One was about fearful flyers who encounter turbulence in the air. “Up in the air 30,000 feet high, the plane rocking back and forth, no place to go, at that point everybody on the plane gets religion. Lord, just let me place my feet on solid ground. What am I trying to say? You can’t get from your point of departure to your point of destination without encountering turbulence.”

The second was about a group of young people who snuck onto the property of an enormous estate where the was a lake filled with crocodiles and alligators and a single small turtle The owner eventually showed up, caught the kids, and offered them a deal. If any of them were willing to jump in the lake, rescue the turtle, and swim to the other side, he would give them anything they wanted. None of the kids responded. The owner turned around to leave, when he heard a splash, turned around, and saw one of the kids in the lake, frantically swimming. The kid dodged alligators, grabbed the turtle, dodged crocodiles, and arrived panting safely on shore.

The owner of the estate said, “I am not sure how you did it but congratulations. Now as I promised, you can have anything you want.”

The young person paused for a moment.

“Well,” he said. “I just want to know who pushed me in the lake.”