During his final State of the Union address, Ronald Reagan etched an epitaph onto the tombstone of welfare liberalism: “The federal government declared a war on poverty, and poverty won.”

For decades, this was the conservative movement’s single-sentence indictment of the Great Society. In the GOP’s telling, the social safety net didn’t just depress economic growth, and rob job creators of their hard-earned capital gains — it also hurt the very “takers” it was meant to help. By encouraging sloth and dependency, government handouts didn’t cure poverty, so much as perpetuate it. Thus, Paul Ryan could insist that there was no contradiction between his avowed commitment to ending poverty and his tireless efforts to throw poor people off their health insurance.

But the Trump White House has mounted a much stranger critique of welfare liberalism, one that is both more realistic — and more sociopathic — than the Reaganite variety.

This week, the White House Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) released its annual report on the state of the American economy. In that analysis, the CEA elaborates on a bizarre argument it first presented last year: Social welfare programs have all but eliminated poverty in the United States — therefore, we should restrict access to such programs by imposing work requirements on them.

“President Johnson’s War on Poverty, based on 1963 standards of material hardship, is largely over and has been a success,” Donald Trump’s economic advisers write. “However, victory was not achieved by making people self-sufficient, as President Johnson envisioned, but rather through increased government transfers.”

In other words, the “rising tide” unleashed by Ronald Reagan’s tax cuts did not lift all boats. Economic growth has proven insufficient for alleviating the material deprivation of America’s most disadvantaged. Were it not for the transfer programs conservatives oppose, poverty would still be a major problem in the United States. But thanks to government handouts, it is not.

You, an ordinary moron, might take this analysis as an argument for expanding government transfers — and/or, raising the minimum wage. After all, if poverty is bad, and welfare programs reliably reduce it, then why not beef up the latter to fully eradicate the former? And if low-income workers aren’t receiving a large-enough share of economic growth to escape poverty through their market incomes, then it would seem wise to raise the floor on wages (especially since the early results from $15 minimum wage experiments have been quite encouraging).

But the economic geniuses in the Trump White House arrive at a very different conclusion. Shortly after announcing that welfare programs had (almost) single-handedly lifted America’s underclass out of poverty, the administration released a budget proposal that would reduce funding for said programs by trillions of dollars. Meanwhile, in its annual report, the CEA calls for adding work requirements to a variety of anti-poverty programs, including Medicaid.

How does the Trump administration reconcile its analysis of the War on Poverty with its desire to wage war on anti-poverty programs? To a certain extent, it simply doesn’t. The president’s draconian agenda appears largely detached from his own White House’s economic analysis. Mick Mulvaney just uses White House budgets the way that “Cannibal Cop” once used internet chat rooms — as a space for sublimating his darkest impulses through sociopathic fantasies.

Nonetheless, while the CEA report doesn’t justify sweeping cuts to the safety net, it does endorse restricting access to social programs through work requirements. The logic of their argument is as follows: Since the War on Poverty worked, and acute material deprivation is no longer much of a problem in the U.S., our focus should be on helping the poor achieve “self-sufficiency,” which is an essential component of human dignity and well-being. And to do that, we must nudge the idle poor out of their welfare hammocks and into the labor market by making government benefits contingent on employment.

Just about every premise of this argument is both logically dubious and morally odious.

The War on Poverty hasn’t been won.

In one sense, the Trump administration’s assessment of the War on Poverty is more honest than Reagan’s: It does not deny that giving poor people money, food, and shelter reliably makes them less poor. Nevertheless, the CEA ultimately ends up giving the existing safety net too much credit for poverty reduction, by understating current levels of material deprivation in the U.S.

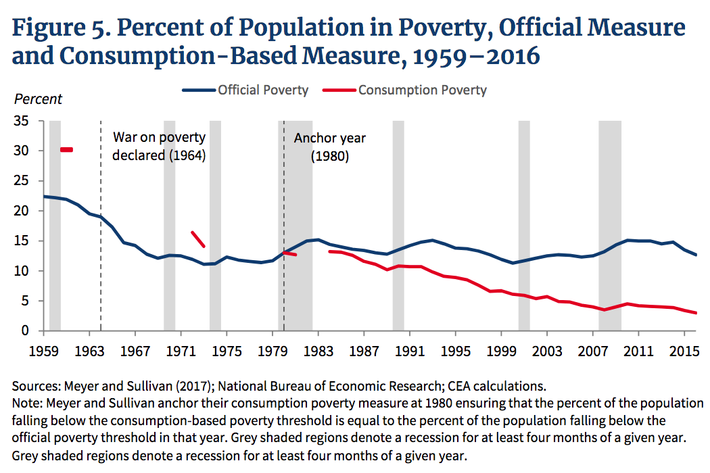

In 2017, the Census Bureau reported that 12.7 percent of Americans were living below the poverty line. The White House insists the actual poverty rate that year was closer to 3 percent. This is because Trump’s CEA measures poverty by consumption levels, while the Census Bureau measures it by income. The logic behind the CEA’s methodology is fairly simple. Some economists have found that Americans tend to underreport their income (especially, the value of their government benefits), while accurately reporting their living expenses. Meanwhile, looking exclusively at what a household earns — rather than what it spends — fails to capture both how much savings that household has, and how much aid it’s receiving from friends and relatives. Therefore, income-based poverty measures could plausibly overestimate the number of households that are genuinely impoverished.

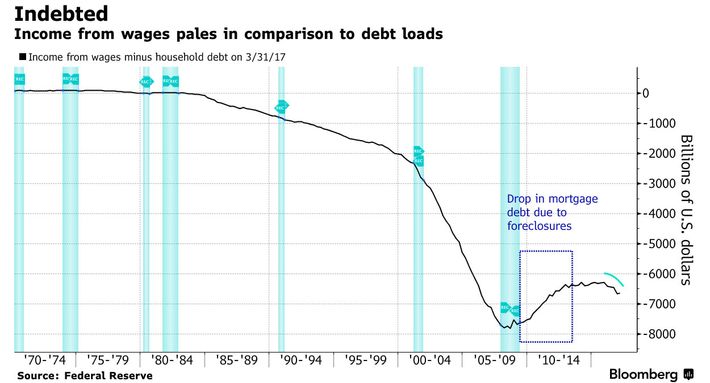

All this is reasonable enough. But every metric has its flaws. And one big problem with a consumption-based poverty measure is that it doesn’t account for household debt. If you are spending money at lower-middle-class levels — but only because you’re wracking up unpayable credit card debts — then your actual financial health is much lower than your consumption would suggest. And in recent decades, Americans’ levels of household debt have been rising sharply.

But the bigger problem with the CEA’s poverty measure is that it’s impossible to reconcile with recent economic history. As Slate’s Jordan Weissmann explains:

Look closely at the CEA’s chart, and you might notice that it suggests the poverty rate was actually higher during the flush 1990s tech boom than during the economic bloodbath of the Great Recession, when joblessness spiked to highs not seen in decades. In other words, it tells us that Americans were better able to afford life’s necessities when 700,000 people were getting fired a month than during a period when America literally had more money than it knew what to do with. Now, that could be a testament to the power of the safety net, which expanded quickly amid the downturn. But it could also mean that the yardstick Meyer and Sullivan created doesn’t actually track the financial hardship families face all that well. Which is it? Thankfully, someone recently put that question to the test.

In a recently updated working paper, Luke Shaefer and Joshua Rivera of the University of Michigan looked at how well Meyer and Sullivan’s consumption-based poverty measure tracks other, more direct signs that families are facing economic adversity, including the share of Americans reporting they’ve had trouble paying for food, utility bills, rent, or medical care. It turns out the official poverty rate and the SPM produced by the Census Bureau have mirrored these things fairly well in recent years. The consumption-based rate poverty rate that the White House prefers has not; it shows that poverty was supposedly in decline, even as more households claimed to be having difficulty covering the cost of meals or shelter.

Ultimately, though, these technical considerations are almost beside the point. Just ask yourself this question: If a country has the highest maternal mortality rate in the developed world, is it plausible that said country has essentially eliminated material deprivation within its borders?

The CEA’s analysis of poverty in the United States says yes. Which seems like all one needs to know about the credibility of that analysis.

Work requirements do not make poor people “self-sufficient,” even by the White House’s bizarre definition of that term.

Once the White House acknowledges that transfer programs reduce poverty, its argument for making the safety net less generous hinges entirely on three claims: Self-sufficiency is a prerequisite for human dignity; to be “self-sufficient” is to support oneself without the aid of welfare programs; and imposing work requirements on welfare beneficiaries is a sound means of making them “self-sufficient.”

We’ll grant the CEA that first normative claim — that self-sufficiency is desirable, and the government should strive to help all Americans attain it. But the White House’s definition of self-sufficiency is nonsense, and its claims about the impact of work requirements are empirically false.

Let’s address the last point first. Does forcing low-income people to enter the labor market — under penalty of losing access to basic medical, food, and housing — reliably free them from dependency on government benefits?

Politifact, citing the research on the topic, says no:

The Congressional Research Service explored a range of sanctions used to encourage financial independence in a 2014 report.

It found that these measures were effective at cutting welfare rolls and produced a “relatively modest” rise in employment. But they fell short in making people self-sufficient.

“The earnings of welfare leavers were typically low, and employment was often not steady,” the report said. “Additionally, a high proportion of welfare leavers continued to receive SNAP (food stamps) after leaving cash assistance.”

… Over the decades, Washington has commissioned studies by RAND, a policy research group, where economist Lynn Karoly specializes in welfare research. Karoly told us that multiple reviews of the research revealed that work requirements “show little effect on family income or income relative to poverty.”

The problem, she explained, is that “the increased earnings are mostly offset by the reduction in cash aid, so that families are no better off in terms of total income.”

Recent experiments with imposing strict time-limits on food-stamp benefits in Kansas and Maine have produced similar results. As Vox reports:

[A] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities audit of the reports on Maine and Kansas found that when actually taking into account the loss of SNAP benefits after being cut off, the difference in income before and after reinstating the work requirements is much less stark than what the White House cited. The total resources (including earnings and SNAP benefits) available to SNAP participants who were cut off was 3 percent lower a year after the cutoff.

All this makes intuitive sense: A little over 10 percent of American workers earn poverty wages — wages so low, those who receive them could work full-time, year-round, and still live in poverty (as the federal government defines it). And a much larger percentage do not earn enough to comfortably get by without Medicaid, food stamps, and housing benefits (and, of course, when one considers all the hidden subsidies affluent Americans enjoy, the percentage of truly “self-sufficient” workers in the U.S. approaches zero percent). Thus, it simply is not possible for all Americans to attain “self-sufficiency,” as the Trump White House describes it, absent a drastic increase in wages at the bottom end of the labor market. And yet, the White House opposes raising the federal minimum wage — and many of its economists believe that the Federal Reserve must not allow the market wage floor in the U.S. to rise drastically, as that would produce intolerable price inflation. Which is to say: The Trump White House does not actually believe that it is possible for all American workers to enjoy “self-sufficiency,” as they define it, in a functioning capitalist economy.

Making it more costly for workers to quit their jobs does not make them more “self-sufficient” under an ordinary human being’s definition of that phrase.

But there is a more fundamental problem with the White House’s argument: Its definition of self-sufficiency is abhorrent.

The CEA does not use that phrase idly; self-sufficiency appears some 50 times in its annual report. And it isn’t hard to understand why. Self-reliance is a bedrock American ideal. Our nation was founded on a (small-R) republican ideology that posited economic autonomy as a prerequisite for political liberty — because “a power over man’s subsistence amounts to a power over his will.” The Jeffersonian ideal of a yeoman’s republic derived from the conviction that only independent landowners, who owned the means of their own sustenance, were capable of genuine self-rule. To be your own boss — answerable to no master save your own will or God or conscience — is among the oldest and most precious of all American dreams.

But this isn’t what the CEA means by self-sufficiency. The White House’s plan doesn’t aim to help food-stamp recipients form worker-owned, cooperative enterprises, or farms. It merely wishes to make the poor less dependent on the federal government — by making them more dependent on their private employers.

In the real world, this means making low-income workers less self-sufficient. Put yourself in the shoes of a Burger King cashier who is constantly sexually harassed by her manager. Would you feel more self-sufficient in a world where you knew that you could quit your job at any time — and still afford your insulin, because there is no work requirement on your Medicaid benefits — or in one where refusing to put up with unwanted advances might cost you access to basic medical care?

This does seem like a difficult question. And it certainly isn’t an idle one: In surveys, roughly 90 percent of female workers in the restaurant industry say they have experienced some form of sexual harassment in their workplaces. And such harassment is only one of the myriad forms of abuse that low-income workers must tolerate in our country. Among other things, many American workers are denied regular bathroom breaks, exposed to all manner of workplace safety hazards, and even robbed of their wages. In a 2017 report, the Economic Policy Institute found that in America’s ten most populous states, “2.4 million workers lose $8 billion annually (an average of $3,300 per year for year-round workers) to minimum wage violations — nearly a quarter of their earned wages.”

The Trump White House has evinced zero interest in reducing these forms of abuse. In fact, it has actually freed employers from the burden of logging all workplace injuries, restored the right of serial labor-law violators to bid on government contracts, and reduced the number of workplace safety inspectors within the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. In other words: The White House’s plan to provide low-income workers with the dignity of “self-sufficiency” involves making it less costly for their bosses to steal their wages — and more costly for them to quit their jobs.

This is not a pro-work policy; it’s an anti-worker one.