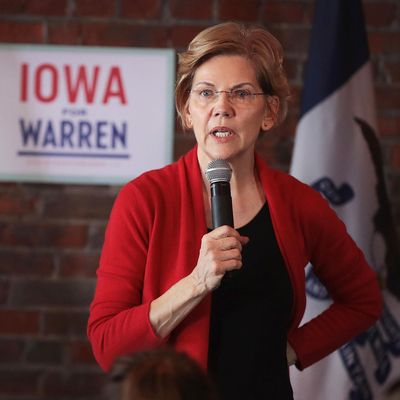

Massachusetts senator Elizabeth Warren is not doing particularly well in early polls of the 2020 Democratic presidential contest, typically bumping along in fifth place with support in the single digits. But she continues to demonstrate that nobody’s going to beat her in sheer heft of policy proposals. In advance of a rural issues forum this weekend in Storm Lake, Iowa, Warren released a proposal applying her general principle of aggressive antitrust enforcement and regulation to Big Ag corporations, as reported by the Des Moines Register:

Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren is taking aim at some of the nation’s largest agribusiness companies, such as Tyson and Bayer-Monsanto, continuing her campaign’s assault on corporate consolidation.

The Democratic presidential candidate’s plan, released exclusively to the Des Moines Register before it was unveiled Wednesday, would address consolidation in the agribusiness industry, “un-rig” the rules she says favor its largest players, and elevate the interests of family farmers.

In her own description of her plan, Warren attacks both horizontal and vertical integration in the agribusiness sector:

The result of mergers and expansions is immense market power. The top four meat processing companies have 53% market share. The three big chicken companies have 90% market share. The two biggest seed companies, Monsanto and DuPont, had 71% of the corn seed market in 2015 — before Monsanto merged with Bayer and DuPont merged with Dow. According to conservative estimates, the newly merged Bayer-Monsanto by itself will control “more than 37 percent of the U.S. vegetable seed market” overall, and will control more than half of the market for some vegetables.

Mergers mean that farmers have fewer and fewer choices for buying and selling, while vertical integration has meant that big agribusinesses face less competition throughout the chain and thus capture more and more of the profits. The result is that farmers are getting a record-low amount of every dollar Americans spend on food, food prices aren’t going down, and agribusiness CEOs and other corporate executives are raking it in. The CEO of the Chinese group that owns Smithfield — a massive meat processing company — made $291 million in 2017 alone.

The senator is promising to reverse anti-competitive mergers in agribusiness — including the recent Bayer-Monsanto merger — and break up vertically integrated corporate arrangements, while fighting corporate contracts and other restrictive practices burdening family farms.

This is a risky approach for Warren, since the companies she is going after are major employers in Iowa and major players politically. But as one economist (and former Democratic congressional candidate) told the Register, it’s also refreshing for a Democratic presidential candidate to offer Farm Belt voters something relevant:

“People are so happy in rural Iowa to see a Democrat talking farm and ag policy, who knows what the price per bushel is, who knows their pain,” [Austin] Frerick said. “Because Democrats just lack a vision for agriculture right now.”

Other than uttering pieties about family farming and ritualistically endorsing ethanol subsidies, urban Democrats generally haven’t had a lot to say when campaigning in the Farm Belt. The last Democratic presidential nominee from Warren’s state, Michael Dukakis, famously drew horse-laughs for suggesting that Iowa corn farmers consider switching to more up-market crops like Belgian endive. Going back further, Bobby Kennedy admitted while barnstorming in Nebraska in 1968 that his main contribution to the farm economy was his large family’s breakfast consumption.

So Warren is again breaking new ground with policy specifics. It’s the sort of thing that might earn her some dedicated Iowa volunteers willing to round up friends and neighbors to caucus for her on a bitterly cold February night next year. But we don’t know yet if other candidates’ charisma or perceived electability — or Republican “Pocohontas” taunts — will matter more.