Human beings evolved to deceive themselves, so as to better deceive each other. This is because we are social animals who spent our formative years living in tight-knit, tribal communities in which our prospects for survival were maximized by maintaining the approval of the collective — while advancing our own individual (and/or factional) interests. And one handy way to reconcile those competing objectives was to develop a talent for inventing ostensibly neutral rules that would, in practice, give you or your crew some distinct advantage in intragroup conflicts — along with arguments for why said rules were ethically necessary, irrespective of their substantive implications.

Over time, however, natural selection weeded out our most gullible ancestors. The surviving homo sapiens had a gift for recognizing the telltale signs of deceit. Soon, they could see that Short Gary’s left eyebrow twitched every time he explained that fairness required giving the tribe’s shortest member the largest slice of fish (as this was what the Founding Fishers had intended). Thus, the Short Garys of the world were killed and eaten. And eventually, their successors developed a more optimal means of camouflaging their own interests in arguments about procedural fairness: They became adept at convincing themselves that justice required whatever arbitrary principle would get them the biggest slice of fish — and thus, betrayed no signs of deceit when trying to convince others.

And this is how a bunch of supernaturally self-deluded apes came to inherit the Earth.

Or so my foggy memory of evolutionary psychology would suggest. And after sifting through a variety of conservative defenses of the Electoral College, it’s hard not to conclude that this account is basically right.

At a CNN town hall Monday night, Elizabeth Warren argued that America should elect presidents by a national popular vote. “We need to make sure that every vote counts. And you know, I want to push that right here in Mississippi. Because I think this is an important point,” the Democratic presidential candidate told a crowd in Jackson. “My view is that every vote matters. And the way we can make that happen is that we can have national voting and that means get rid of the Electoral College.”

An overwhelming majority of the American public agree. And yet, an overwhelming majority of GOP operatives, public intellectuals, and politicians do not.

The simplest explanation for this discrepancy is that professional Republicans believe (consciously or otherwise) that the existing election rules benefit their party. After all, the GOP has lost the popular vote in six of the last seven presidential elections. And since the Electoral College gives disproportionate influence to whiter, more rural states — and the GOP is becoming increasingly reliant on white, rural voters — the existing conservative coalition is poised to continue deriving a benefit from the status quo rules for cycles to come.

This puts conservative pontificators in the unenviable position of having to defend an archaic, undemocratic system that does not work as its authors intended, or as the American public desires, on the grounds that it is a uniquely fair and rational way of electing the nation’s most powerful officeholder.

Terrible arguments ensue. And these awful products of motivated reasoning are joined by the awful products of status quo bias (which leads some small number of liberals to defend the Electoral College) in a noxious stew of nonsensical arguments against allowing popular democracy to determine control of at least one branch of our government.

Fortunately, I (and everyone who agrees with me on this subject) have escaped the shackles of subjectivity, and know the objective truth about the Electoral College. And so, I can provide you, dear reader, with a rundown of some of the most prominent arguments for preserving that vile institution — and why all of them are wrong. Defenses of the Electoral College tend to fall into one of three broad categories, and so we’ll examine each genre in turn.

1. The Electoral College currently exists, therefore it is good.

(A) The founders thought superhard about this, and so we should defer to their judgement.

From Allen Guelzo and James Hulme’s Washington Post op-ed, “In Defense of the Electoral College”:

The Founders who sat in the 1787 Constitutional Convention lavished an extraordinary amount of argument on the electoral college, and it was by no means one-sided … The Founders also designed the operation of the electoral college with unusual care. The portion of Article 2, Section 1, describing the electoral college is longer and descends to more detail than any other single issue the Constitution addresses. More than the federal judiciary — more than the war powers — more than taxation and representation.

This isn’t the op-ed’s only argument. But the authors devote a solid 350 words of their short column to saying, essentially, “Look, our finest slaveholders already debated all this only a couple decades before the advent of the steam engine, so why reopen this can of worms?” And they are hardly alone in presenting “the founders said so” as a trump card.

The trouble with this argument is twofold. First, the founders were (mostly) a collection of land speculators who built their fortunes by ethnically cleansing Native Americans, and slavers who built theirs by participating in one of the greatest atrocities in world history. Most did not believe in popular democracy (as the vast majority of Americans do today). As political theorists, these dudes were so foresighted, they assumed that America would never have political parties.

None of this means that some of them weren’t brilliant, or that they didn’t build some institutions that are worth preserving. But it does mean we’re talking about incredibly flawed, extremely dead human beings, not philosopher kings appointed by God. Thus, there is no reason to reflexively defer to their judgement — which was itself the product of compromise between disparate interests, not Socratic dialogue on the ideal form of the state. Some founders favored the popular vote; others wanted to leverage their chattel into disproportionate political power.

Understandably, Hulme and Guelzo are eager to deny these grubby origins, writing:

Above all, the electoral college had nothing to do with slavery. Some historians have branded the electoral college this way because each state’s electoral votes are based on that “whole Number of Senators and Representatives” from each State, and in 1787 the number of those representatives was calculated on the basis of the infamous 3/5ths clause. But the electoral college merely reflected the numbers, not any bias about slavery (and in any case, the 3/5ths clause was not quite as proslavery a compromise as it seems, since Southern slaveholders wanted their slaves counted as 5/5ths for determining representation in Congress, and had to settle for a whittled-down fraction). [Emphasis mine.]

There are multiple issues with this defense. For one thing, some southern framers were quite forthright about the nature of their concerns. As Jamelle Bouie notes:

Hugh Williamson of North Carolina made this point explicit in his objection: Because there won’t always be “distinguished characters” with national recognition who could win a majority of votes, “the people will be sure to vote for some man in their own State, and the largest State will be sure to succeed.” But this will not be Virginia, “since her slaves will have no suffrage.”

And even if this hadn’t been the case, Hulme and Guelzo’s argument would be nonsensical. If the framers had adopted a popular-vote system, then only the enfranchised would have influenced presidential elections — and thus, slavers wouldn’t have been able to leverage their human property into outsized political influence. This is not complicated. Furthermore, what, precisely, is “in any case, the 3/5ths compromise wasn’t that pro-slavery since the plantation owners wanted it to be 5/5ths” supposed to prove?

But the most fundamental problem with the idea that we should defer to framer’s judgement is this: Almost immediately after writing the rules for presidential elections into the Constitution, the leaders of our republic realized they’d made a mistake (which is why the 12th Amendment exists). Among other things, making the Electoral College runner-up the vice-president proved to be deeply problematic the moment political parties took hold. If we were actually committed to honoring the founders’ intentions, then Hillary Clinton would be Donald Trump’s vice-president today. This would surely make for a fine sitcom premise, but few would describe it as a rational way to run a White House.

(B) It would put us on a slippery slope to abolishing the Senate.

From Red Jahncke’s column in The Hill, “Think We Should Do Away With the Electoral College? Think Again.”

We are both a democracy and a federation of states. The Electoral College was designed specifically to prevent the tyranny of big states over small states, as was the U.S. Senate, which affords all states, large and small, equal representation. If we do away with the Electoral College, we might as well do away with the Senate.

Guelzo offers similar sentiments in another pro–Electoral College piece for National Affairs:

Abolishing the Electoral College now might satisfy an irritated yearning for direct democracy, but it would also mean dismantling federalism. After that, there would be no sense in having a Senate (which, after all, represents the interests of the states), and eventually, no sense in even having states, except as administrative departments of the central government.

The biggest problem with this slippery-slope argument is that it’s implausible: There is strong majoritarian support for abolishing the Electoral College, and a way to effectively nullify it without changing the Constitution (the National Popular Vote interstate compact). This is not the case for abolishing the Senate.

But the more basic problem with this species of Electoral College defense is that it boils down to “federalism exists, therefore it ought to.” Why states shouldn’t exist as mere administrative departments of a central government (with some measure of local autonomy) goes largely unexamined. It is not as though our state lines were drawn for the purpose of giving centuries-old, indigenous ethnic groups the opportunity to exercise a modicum of self-determination. Rather, most state lines don’t even have a geological basis, and merely reflect the political interests of those in power when they were drawn. It is not as though Wyoming’s white majority has an ancient connection to its land, and a distinct culture that fundamentally divides them from the other peoples of the Mountain West. There is no reason to treat it as a semi-sovereign entity that must be indulged, lest it break from the union. We are not an infant republic anymore. A secession crisis is very low on our list of tail risks.

There may be some virtue in decentralizing power and creating opportunities for policy experimentation on the subnational level. But that does not require inflating Wyoming’s influence over presidential elections or congressional legislation.

By contrast, the case for not requiring all legislation to pass through an upper chamber that is wildly malapportioned — such that Wyoming residents get 66 times more say in the Senate than Californians do — is quite simple: In a democracy, individual citizens should have roughly equal representation in their governing institutions. Achieving perfect equality in this respect is impossible; but designing a more representative legislature than the U.S. Senate is not. In fact, every U.S. state has already done so. If abolishing the Electoral College will eventually destroy the Senate, that only makes the case for Warren’s proposal more compelling.

2. Abolishing the Electoral College would definitely have this bad effect, for reasons so logically sound I don’t need to provide evidence for them (even though other defenders of the Electoral College insist it would have the opposite effect, which would also be bad).

(A) It would give too little political power to white people.

Earlier this year, former Maine governor Paul LePage argued that under a national popular vote, “white people will not have anything to say. It’s only going to be the minorities that would elect. It would be California, Texas, Florida.”

It is unclear how a national popular vote would result in only Californians, Texans, and Floridians having a say in presidential elections. Regardless, more than 70 percent of the residents of California, Texas, and Florida identify as white, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

(B) It would give too much political power to white people.

Political scientist Amel Ahmed, meanwhile, argued in the American Prospect in 2016 that abolishing the Electoral College would be unfair to nonwhite people:

It’s widely recognized that without the Electoral College, one could win the presidency with a few key states. Even more troubling, though, is that without the Electoral College one could win by just appealing to white voters. Since white voters constitute a majority of the electorate, at least for now, that might actually be the easiest road to the presidency for some candidates.

The Electoral College is designed to protect minority interests in a variety of forms, whether economic, ideological, or racial. Black and Latino voters draw considerable attention because, in several states, their votes are pivotal. That affords minorities a seat at the table that they might not otherwise enjoy.

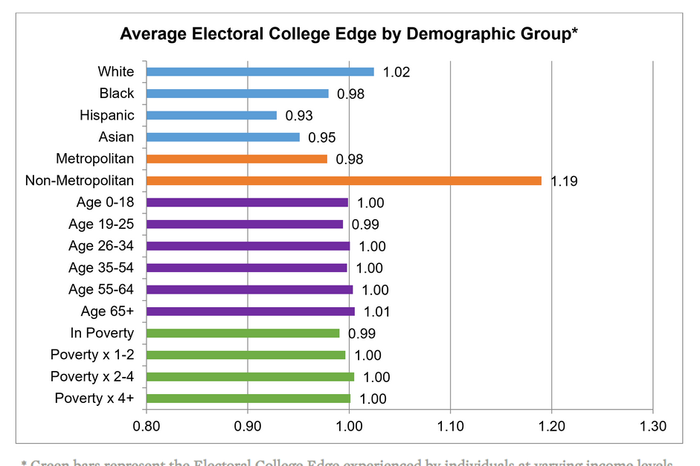

This is an odd claim. Small states are overrepresented in the Electoral College (since they all automatically get at least three electoral votes, no matter the size of their population). And since small states are whiter, on average, than large ones, nonwhite voters are underrepresented in the Electoral College, as the sociologist Sean Darling-Hammond has shown:

Furthermore, it is unclear why candidates would lose all incentive to court the votes of racial minorities in a popular-vote context. The dividing lines of American politics could eventually change. But for the foreseeable future, it is hard to fathom how a Democratic nominee could win a national majority while appealing exclusively to white people.

And yet, as is so often the case with pro–Electoral College arguments, Ahmed feels no need to back up her intuition with data of any kind. In fact, mere paragraphs later, she undermines her own claim:

Trump managed to reach across a broader set of economic and geographic constituencies than any other candidate: Rust Belt voters and rural ones; blue-collar and white-collar voters; economic nationalists and fiscal conservatives.

The Electoral College forced the winning candidate to appeal to a wide variety of different kinds of white people. Therefore, abolishing it would reduce the influence that African-Americans and Hispanics enjoy over our political system?

(C) It would give large states too much power.

This might be the single most popular argument against abolishing the Electoral College. Here is one representative example, from Michael Barone of the American Enterprise Institute:

The case against abolition is one suggested by the Framers’ fears that voters in one large but highly atypical state could impose their will on a contrary-minded nation. That largest state in 1787 was Virginia, home of four of the first five presidents. New York and California, by remaining closely in line with national opinion up through 1996, made the issue moot.

California’s 21st century veer to the left makes it a live issue again. In a popular vote system, the voters of this geographically distant and culturally distinct state, whose contempt for heartland Christians resembles imperial London’s disdain for the “lesser breeds” it governed, could impose something like colonial rule over the rest of the nation. Sounds exactly like what the Framers strove to prevent.

Barone does not explain how a national popular vote would enable the 12 percent of Americans who live in California to impose “something like colonial rule” over the rest of the country. Nor does he address the fact that the Golden State is still home to millions of rural-dwelling Republicans, who currently enjoy no effective say in presidential elections. It is difficult to discern any coherent ideologically (or racially) neutral principle that would explain Barone’s outrage at the thought of individual Californians’ having the same influence in elections as their countrymen in smaller states (by which he ostensibly means white rural ones, and not, say, residents of the District of Columbia).

More broadly, the “counting votes equally would give voters in populous states too much power” is just a long-winded way of saying that one does not believe in democracy. Why shouldn’t national candidates campaign in the places where most people live? Congress already guarantees that every region will have some say over policy-making — and that, within the Legislative branch, small states will actually have disproportionate say. What is it, exactly, about people who live in big cities that make them so undeserving of democratic equality?

(D) It would give small states too much power.

In 2012, then-federal judge Richard Posner argued that abolishing the Electoral College would be unfair to large states:

The Electoral College restores some of the weight in the political balance that large states (by population) lose by virtue of the mal-apportionment of the Senate decreed in the Constitution. This may seem paradoxical, given that electoral votes are weighted in favor of less populous states … But winner-take-all makes a slight increase in the popular vote have a much bigger electoral-vote payoff in a large state than in a small one. The popular vote was very close in Florida; nevertheless Obama, who won that vote, got 29 electoral votes. A victory by the same margin in Wyoming would net the winner only 3 electoral votes. So, other things being equal, a large state gets more attention from presidential candidates in a campaign than a small states does.

It is certainly true that our “winner take all” system can, in some circumstances, give slim majorities in large states wildly disproportionate influence in elections. And that fact should probably give second thoughts to any Electoral College defender who sincerely values to disempowering large states, for ideologically neutral reasons. But the fact that the Electoral College may one day give the residents of a large state like Texas profound clout in presidential elections in no way ameliorates the underrepresentation of New Yorkers, Californians, or residents of other populous, deep blue states.

3. Abolishing the Electoral College would plunge our republic into a nightmarish political system identical to the one we currently live under.

(A) Candidates would not campaign much in rural areas.

This argument is too ubiquitous to require an example, even though it is dumb on a variety of levels. First, the state of Texas elects its senators by popular vote, and yet, this did not cause Beto O’Rourke to campaign exclusively in Dallas, Houston, and Austin last year. In statewide races — even in large states — candidates still put in some appearances outside major metro areas, and there’s no reason to think this wouldn’t hold true for national elections held by popular vote. Second, while presidential candidates do currently make some token appearances in rural areas — and would likely continue to, even without the Electoral College — they already focus overwhelmingly on urban ones, because very few voters live in low-density areas, by definition. As political scientist Robert Speel observes:

Presidential candidates don’t campaign in rural areas no matter what system is used, simply because there are not a lot of votes to be gained in those areas. Data from the 2016 campaign indicate that 53 percent of campaign events for Trump, Hillary Clinton, Mike Pence and Tim Kaine in the two months before the November election were in only four states: Florida, Pennsylvania, North Carolina and Ohio. During that time, 87 percent of campaign visits by the four candidates were in 12 battleground states, and none of the four candidates ever went to 27 states, which includes almost all of rural America.

Even in the swing states where they do campaign, the candidates focus on urban areas where most voters live. In Pennsylvania, for example, 72 percent of Pennsylvania campaign visits by Clinton and Trump in the final two months of their campaigns were to the Philadelphia and Pittsburgh areas. In Michigan, all eight campaign visits by Clinton and Trump in the final two months of their campaigns were to the Detroit and Grand Rapids areas, with neither candidate visiting the rural parts of the state.

Finally, it’s worth noting that, contrary to Lindsey Graham’s ostensible belief, one doesn’t need to wait in line to shake hands with a politician to get involved in politics. It seems likely that, under a national popular-vote system, presidential nominees would continue to campaign mostly near major population centers. But, unlike in our present system, the God-fearing conservatives of upstate New York, eastern Maryland, rural California — and every other bastion of Real Americanism within a blue-state Gomorrah — would actually have a reason to get involved in presidential elections. Waving a sign at a presidential rally might be fun. But knocking on doors, registering your friends to vote, and organizing a mini turnout operation are more significant forms of political participation. And you don’t need a candidate to visit your region to engage in such activity — but you probably do need to know that your vote will really count. Thus, a national popular vote would give rural Americans more opportunities to engage meaningfully in politics, not less. To believe otherwise, you’d have to think that small-town folks are incapable of any political action beyond attending a candidate’s speech. Which is to say: You’d have to have “contempt for heartland Christians.”

(B) Third-party candidates would sometimes act as spoilers.

Here’s Guelzo again:

A final unforeseen benefit of the Electoral College is that it reduces the likelihood that third-party candidates will garner enough votes to make it onto the electoral scoreboard. Without the Electoral College, there would be no effective brake on the number of “viable” presidential candidates. Abolish it, and it would not be difficult to imagine a scenario in which, in a field of dozens of micro-candidates, the “winner” would need only 10% of the vote, and would represent less than 5% of the electorate.

Setting aside the question of whether this (unsubstantiated) prediction is plausible: The problem identified here is not inherent to a national popular vote, but rather, to a winner-take-all system. Implementing ranked choice voting and/or runoff elections would solve the spoiler issue (that already exists).

(C) It could lead to a situation where American politics is defined by polarization, and high levels of social animosity.

The author Garett Jones argued in 2012 that the Electoral College was indispensable, as it is a “great tool for reducing social conflict” in American politics:

We rarely hear too much about regional issues in the U.S. other than farmers vs. everyone else. But if the presidency was decided by majority rule, I’m sure we’d hear a lot more about regional differences. Could a presidential candidate get 75% of the votes in Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Florida by promising broad-based Gulf Coast subsidies and a few other goodies? Could a candidate get 85% of California’s and New York’s votes partly by offering housing subsidies for people facing high housing costs?

I don’t know: But if we got rid of the electoral college and had a popularly elected president we’d sure have a chance to find out.

As it stands, presidential candidates are trying to appeal to the median voter in each state across a large number of states. That’s how you get to be president. This reduces regional tensions because candidates are never trying to get 90% of the votes in a state. When you’re pitting 90% of one region of the country against 90% of another region of the country, you’re substantially raising the probability of social conflict.

Too many civil wars are based on regional differences for this to be no big deal.

This is, of course, yet another argument rooted in pure, unsubstantiated conjecture. But even if Jones is right that a national popular-vote system would increase the salience of regional divisions in American politics, that would likely reduce social conflict in the U.S. “If we’re not careful, we could end up in a world where our politics centers on the dangerously divisive question of how much the federal government should subsidize the Gulf Coast, instead of innocuous matters like whether Central American migrants are invading our country in a bid to ‘violently change’ its culture” is an awfully strange sentiment! And yet, Jones believes his argument holds up in the Trump era, as he (and some center-right thinkers) promoted it on social media just this week.

In reality, the most explosive divides in American politics today lie on questions of race, pluralism, and national identity. These divisions do map onto our nation’s geography. But the split isn’t between regions or states; it’s between city and country. Our republic would be in much better shape if its defining conflict was how to balance disparate regions’ economic interests. “New York wants more federal housing subsidies, while Arkansas wants more rural development block grants,” is a disagreement that can be resolved through compromise. “Urban cosmopolitans believe we are a nation of immigrants and diversity is our strength, while rural nationalists insist that we are a white Christian nation that can’t sustain its civilization with other people’s babies” is not.

Of course, there is no reason to believe that a national popular vote would increase the salience of regional conflict in American politics. The primary reason major-party standard-bearers must evince some concern for the interests of disparate regions of the country is not the Electoral College, but the U.S. Congress. An economic program that aided major coastal population centers — at great expense to all regions in between — would not make it through the House, let alone the Senate.

(D) It would create a political system in which an unqualified “media personality” could win the presidency.

Finally, the aforementioned Jahncke explains that, in a popular-vote system, “candidates would campaign in big media markets,” and this “would favor media personalities and celluloid campaigns.” In other words: If it weren’t for the Electoral College, America would face a serious risk of electing some random celebrity to the highest office in the land.

Perhaps I’ve just deceived myself so as to better deceive you. But I just don’t think that is a very good argument.