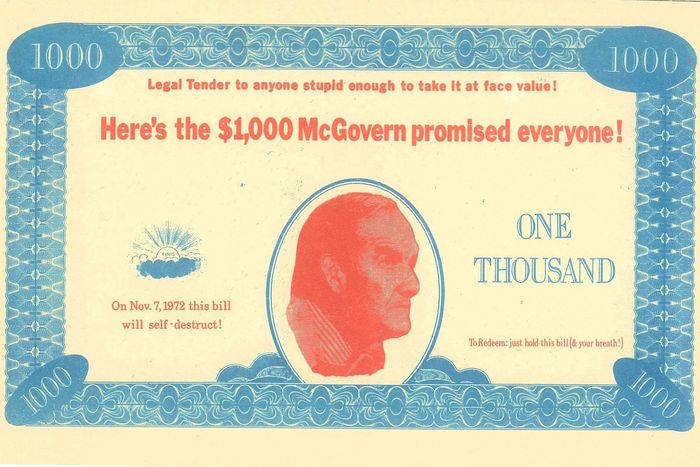

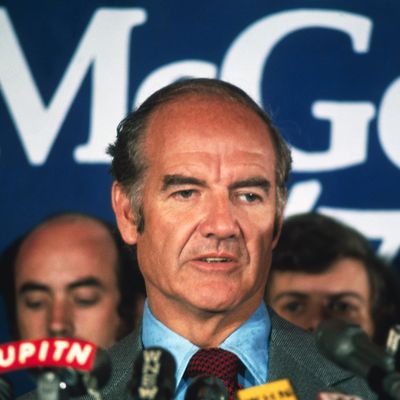

For political observers of a certain vintage, long-shot presidential candidate Andrew Yang’s proposal to give every American adult $1,000 a month brought back a distinct memory from 1972. That year Democratic presidential nominee George McGovern also proposed writing a $1,000 check to every American — $1,000 a year, however (there’s been a lot of inflation since then).

To put it mildly, it did not go over well. Even though McGovern eventually abandoned the proposal, and even though it was similar to the “negative income tax” idea crafted by famed free-market economist Milton Friedman and briefly considered by Richard Nixon, the plan became a potent symbol of the Democrat’s alleged radicalism, fiscal irresponsibility, and wooly thinking. Even before Republicans began mocking him over it, primary rival Hubert Humphrey — hardly a conservative on domestic issues — blasted the proposal with both barrels, claiming it would lead to a massive middle-class tax increase while undermining incentives to work. It probably caused McGovern more grief than anything else he had control over in that campaign, which ended with him losing 49 states to Nixon.

The idea of an income floor has become less radical-sounding over the years. The refundable earned-income tax credit, another Republican idea that was promoted most aggressively by Bill Clinton, is basically a negative income tax, albeit one that is means-tested and comes with an implicit work requirement. And in the policy world, a full-fledged universal basic income is discussed regularly as a feasible strategy for addressing poverty.

But despite its familiarity to wonks, and its support from some conservatives (who love its potential for destroying bureaucracy) as well as progressives, UBI has never fully been tested anywhere, as Nathan Heller observed last year:

Recent interest in U.B.I. has been widespread but wary. Last year, Finland launched a pilot version of basic income; this spring, the government decided not to extend the program beyond this year, signalling doubt. Other trials continue. Pilots have run in Canada, the Netherlands, Scotland, and Iran. Since 2017, the startup incubator Y Combinator has funded a multiyear pilot in Oakland, California. The municipal government of Stockton, an ag-industrial city east of San Francisco, is about to test a program that gives low-income residents five hundred dollars a month. Last year, Stanford launched a Basic Income Lab to pursue, as it were, basic research.

Given the enormous scale and cost (Yang’s proposal would cost an estimated $3.9 trillion a year), something this untested is going to make a lot of people nervous. And while a competing idea of similar scale, a federal jobs guarantee, is quite popular, UBI is a tougher proposition, precisely because it does not require work. One Gallup poll about UBI strictly for people who lose their jobs to artificial intelligence — presumably a group with whom everyone would sympathize — showed a narrow majority opposed.

Perhaps just as importantly in terms of bipartisan support, UBI really plays into conservative conspiracy theories about Democrats wanting to bribe the undeserving poor to vote for them with other people’s tax dollars. Some of the youthful Yang Gang’s loose talk about their hero’s UBI proposal — and his staunch support of marijuana legalization — probably reinforces that problem:

So far, Yang is doing a lot better than anyone had any reason to expect from an obscure businessman with no political experience, and his championship of UBI certainly has a lot to do with it. But there’s a reason no other candidate in a left-leaning presidential field has gone there so far. It’s an idea that has already helped kill one presidential nominee’s candidacy, and others are reluctant to test whether it might kill again.