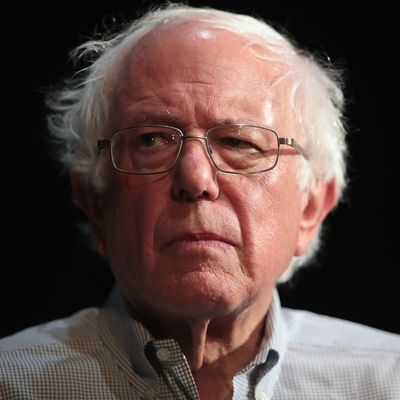

To imagine that Bernie Sanders could be elected president and enact something resembling his agenda requires a number of extremely generous assumptions. Perhaps the most realistic of these is that Senate Democrats eliminate the legislative filibuster, bringing the number of senators needed to vote for Medicare for All, a Green New Deal, and other ambitious programs from a completely unimaginable 60 to a still wildly unlikely 50.

Sanders himself, however, opposes such a maneuver. In 2013, Sanders appeared to favor majoritarian reforms, but he has veered sharply and inexplicably to the right. Two months ago, he said he “not crazy about getting rid of the filibuster.” In an interview with Amanda Terkel, Sanders reiterates his view, because “you have to protect minority rights.”

This is an odd argument to make. The federal government, by design, makes it unusually difficult to pass new laws, which require concurrent majorities in three separately elected bodies. On top of that, one of those bodies, the Senate, is designed to give disproportionate voting power to citizens who live in sparsely populated states. And on top of that, the Senate has yet another feature that evolved entirely by accident: a supermajority requirement. The filibuster evolved out of a weird historical glitch, and the number of senators required to end it has changed over time, currently standing at 60.

Sanders normally treats unique features of American government with some suspicion. (“The U.S. is the only major country on earth that doesn’t guarantee health care to all people” is something he has pointed out some 80 gazillion times.) Most democratic legislative bodies in the world allow the side that has more votes to win. Why does Sanders believe political minorities, who can block laws merely by winning either the House or the Senate or the presidency, need extra rights?

Sanders is correct, of course, that sometimes Republicans have control of the House, Senate, and presidency, and during those moments, a supermajority voting requirement helps Democrats. But the notion that the filibuster helps Democrats as much as it helps Republicans seems fanciful. Progressives generally tend to support more change than conservatives, and the changes they do enact are more likely to stick. On the whole, repealing all the laws ever passed would benefit conservatives more than liberals. This is why Orrin Hatch correctly declared the filibuster is “what’s prevented our country for decades from sliding toward liberalism.”

Because the Senate’s procedures are so unwieldy, senators have created multiple carve-outs. They do not necessarily follow a rational pattern. Both parties have eliminated the filibuster for judges. That means passing a law requires 218 House votes, 60 Senate votes, plus the president, while just 50 Senate votes and the president — and no House vote at all — can confirm a jurist for a lifetime appointment that confers supreme final authority to strike down any law. Nobody would or did design a system with such a massive bias toward inaction.

And yet one of the oddities of the filibuster is that, even though it has repeatedly evolved, senators have come to treat its byzantine features as hallowed traditions passed down from on high. Sanders defends the possibility of passing his agenda by highlighting another workaround, called budget reconciliation. “I do think that every piece of legislation that I am fighting for can be passed with good legislative processes, including budget reconciliation,” he tells Terkel.

Budget reconciliation is one of the ways the Senate manages to hobble around the filibuster. It’s a rule that allows the chamber to pass annual fiscal bills with a majority vote. The rules are designed to allow changes to taxes and spending to pass with 50 votes, so that that government can enact budgets. But reconciliation bills can only enact changes to taxes and spending.

What this means is that a party that has control of government, but lacks 60 Senate votes, has an overwhelming incentive to cram its agenda into a form that can pass via reconciliation. But, as any expert in Senate procedure will tell you, it’s not a “good legislative process.” It’s a terrible legislative process. It forces the majority to make laws without being able to change regulations.

One of the obstacles Republicans faced when they tried to repeal Obamacare was that using reconciliation prevented them from designing an alternative even if they wanted to. Reconciliation would probably prevent Medicare-for-all or any real single-payer plan. Needless to say, any attempt to break up the financial industry, increase the minimum wage, or pass any other major reform would be completely ineligible under budget reconciliation procedures.

Sanders is trying to simultaneously argue that a supermajority requirement is needed to protect political minorities, and that there is already an effective process to let the majority pass new laws. The filibuster is bad for (small-d) democrats and (large-D) Democrats. That the most left-wing member of the Senate is justifying minority-rule processes whose only justification is to inhibit progress may be the single most baffling position any candidate has taken.