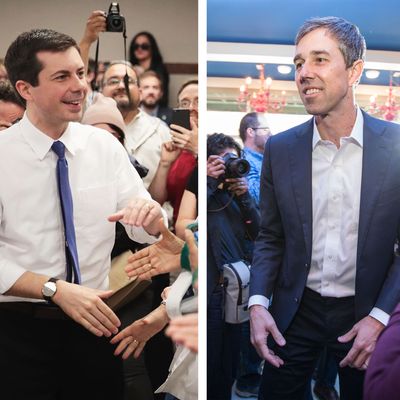

Anyone paying close attention to the early phases of the 2020 Democratic presidential nominating contest cannot help but notice an almost dialectical relationship between two young white male candidates, Beto O’Rourke and Pete Buttigieg, thought to be “charismatic,” but in quite different ways. Neither has the kind of credentials usually associated with successful presidential candidacies, but both have already had alternating meteoric moments in national media and the polls.

Earlier this year “Beto-mania” was a thing, as a once-obscure three-term House member from West Texas who set fundraising records while throwing a scare into Ted Cruz in the 2018 midterms had former Obama political aides signing up for his presidential effort, and drew big and youngish crowds everywhere he went. But more recently South Bend, Indiana, mayor Pete Buttigieg has taken off like a rocket, sporting an unconventional biography (he’s a married, gay, devoutly Christian, multilingual, Afghanistan veteran) and an undeniably media-savvy knack at telling “narratives,” particularly concerning the economic struggles of the Rust Belt, where most Democrats feel they must beat Trump.

As Mayor Pete soaked up media attention, O’Rourke seemed to shrink from it, focusing on early-state travel and the kind of small but intense voter interactions that made him a legend in Texas. As Max Greenwood recently observed, it’s raised some eyebrows:

Former Rep. Beto O’Rourke (D) is avoiding televised town halls and appearances on the national news circuit in his presidential campaign, employing many of the same tactics he used in his nearly successful bid to unseat Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas) in last year’s midterm race.

But using the same game plan in the presidential race is looking increasingly risky as the former Texas congressman battles for space and attention in a crowded Democratic field.

Whether or not there’s any causal relationship between Beto’s occlusion and Buttigieg’s emergence, it’s hard to miss the fact that they’ve been moving in different directions:

[O’Rourke] has invariably drawn comparisons to another 2020 hopeful, Pete Buttigieg, the 37-year-old mayor of South Bend, Ind., who has seen his political stock rise in recent weeks amid a series of high-profile media appearances, including a well-received CNN town hall in March that earned him widespread attention.

“He, in large part, has risen in prominence because he says yes to every single interview,” said Nate Lerner, who previously ran Draft Beto, a group that sought to recruit O’Rourke into the presidential race. “He’s relentless, going on TV, going on every single podcast.”

Coincidentally or not, the two men have represented bandwagons heading in different directions in the polls. O’Rourke briefly reached double digits in three national polls in March, immediately after his announcement of candidacy, even as Mayor Pete languished in obscurity. In a CNN poll taken from March 14–17, for example, Beto was at 11 percent while Buttigieg was at one percent. But in a Monmouth survey released earlier this week, Buttigieg was at 8 percent and O’Rourke was down to 4 percent.

So is the Texan doing better in those early states where he’s cultivating grassroots relationships? Not really. Though polling in these states is too sparse to be definitive, it does show the same trends as national polls. In RealClearPolitics’ average of Iowa polls, Buttigieg is at 11.3 percent and O’Rourke is at 5.3 percent. In New Hampshire, the RCP averages show Mayor Pete at 13 percent and Beto at 4.5 percent.

Some observers argue that the very intensity and size of the early competition has “nationalized” the Democratic race:

“In my opinion, we’ve seen a nationalizing of the 2020 primary, where early state polling isn’t so different from national poll results,” said Christy Setzer, a Democratic strategist.

“That’s markedly different from years past, where really working the turf in Iowa and New Hampshire — regardless of whether it grabbed national headlines — paid dividends. This year, it’s all TV, TV, TV.”

There is certainly precedent for candidates operating under the radar in early states, focusing on building a campaign infrastructure that will flower into support later on — particularly in Iowa, whose caucuses require a serious organizing effort. O’Rourke’s campaign manager, Jen O’Malley Dillon, has extensive Iowa experience, and an impressive résumé including service as executive director of the Democratic National Committee and deputy campaign manager for Obama in 2012.

Sometimes the “to the masses!” approach has worked in Iowa, while other times it hasn’t. In 2012 Republican Rick Santorum was all but invisible nationally as he labored through low-cost Pizza Ranch venues and reached all 99 Iowa counties. On caucus night he won, and wound up being Mitt Romney’s most durable opponent. But in the 2016 cycle, former Maryland governor Martin O’Malley did everything Democratic candidates are supposed to do in Iowa, investing in state and local candidates early on and practically living in the state — and was crushed by the national Clinton and Sanders juggernauts.

What Santorum had that O’Malley lacked was an ideological connection with likely caucusgoers that attracted and mobilized them more than all the media buzz ever could. And that raises the question as to whether the decidedly nonideological O’Rourke campaign can make the same kind of connections via sheer personal charisma at a time when so many other candidates are offering Democratic voters red meat and policy specifics.

Meanwhile Pete Buttigieg has to show he can build an actual grassroots organization from the money and fame his charisma has generated, as CNN recently noted:

The campaign hopes to have 50 people on staff by the end of the month.

That still pales in comparison to some of his competitors, like Sen. Elizabeth Warren, who boasts upwards of 170 people on staff.

And while the team is eyeing staffers in early states, none have been announced. Nor have campaign offices in Iowa, New Hampshire, Nevada or South Carolina been opened — a dramatic difference between candidates like Warren, Sen. Kamala Harris and even candidates like former Rep. John Delaney, who has more than 20 staffers and eight offices in Iowa.

Recent history has also been marked with candidates whose buzz and national poll standings never translated into a workable campaign organization, like momentary Republican sensation Ben Carson in 2016.

So both of these young white men with the unconventional backgrounds could turn into flashes in the pan, which would gratify those who think they’ve gotten undue attention at the expense of candidates who are women or people of color. But if they both survive, we will eventually find out whether one’s success means the other’s failure.