Americans owe at least $1.5 trillion in student loan debt. That stark figure drives up rates of poverty among the elderly and depresses rates of home ownership and parenthood among young adults. Public college tuition, meanwhile, continues to rise so extravagantly that it consistently outpaces the amount of aid offered to students in need. Student debt is a national crisis, and candidates angling for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination in 2020 are likely to address it repeatedly on the campaign trail. Senator Bernie Sanders ran on the promise of free public college in 2016, and may owe his popularity with younger voters in part to his free college proposal.

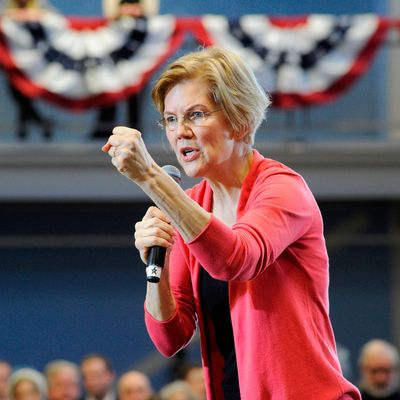

But Sanders has some stiff competition for that vote, and for the title of furthest-left candidate in general. Senator Elizabeth Warren escalated her years-long war on student loan servicers on Monday, when her campaign released a sweeping student debt proposal that will likely set a standard for other candidates. Warren, in a Medium post, explained that her plan would cancel $50,000 of public and private student loan debt for individuals with household incomes under $100,000. Households making between $100,000 and $250,000 would receive partial debt cancellation; as the Daily Beast noted, the cancellation amount would then decline by “a dollar for every three dollars in income” above that $100,000 threshold, while households making over $250,000 would not receive any relief. A person with a household income of $160,000 could expect to shed $30,000 in student loan debt, according to an example included in Warren’s post. Seventy-five percent of student loan borrowers would have their debts completely wiped out. Warren added that she’d pay for the proposal — which also calls for the elimination of public college tuition — with a 2 percent tax on households making $50 million a year or higher.

Warren’s proposal doesn’t just set a standard for sheer generosity. It also links wealth redistribution explicitly to the resolution of long-standing racial inequities. If her proposal ever becomes law, it would also create a $50 billion federal fund for historically black colleges and universities, prohibit public colleges from considering an applicant’s citizenship status in the admissions process, and provide extra funding to states that improve college enrollment and graduation rates for students of color. One uniquely transformative position would end federal funding to for-profit schools. As sociologist Tressie McMillan Cottom exhaustively documented in her 2017 book, Lower Ed, for-profit schools aggressively target working-class, first-generation college students, who are disproportionately likely to be women and people of color. Students who attend for-profit schools tend to leave with high debt and credentials they often can’t use, and are thus more likely than average to default on their loans. Warren would make it much more difficult for these schools to stay in business. At the same time, she introduced a raft of proposals that would make it easier for students of color to not only enroll in legitimate colleges, but graduate.

Overall, Warren’s new proposals are welcome entries to the student loan debate, but they aren’t without their flaws. Income-based standards for debt cancellation would reduce or even withhold assistance from some households. On paper, a household income of $100,000 seems high. But in expensive areas, household income isn’t necessarily a useful way to gauge a family’s ability to pay back student loans. Factor in the cost of rent or a mortgage, plus transportation costs, groceries, child care, and medical expenses, and $100,000 can evaporate with frightening speed. And while it may be difficult to feel much sympathy for anyone making over $250,000 a year, individuals in high-earning professions can carry massive, life-altering student debt loads. Research reported by Stat in 2017 shows that medical school graduates now owe an average of $176,000 in student loan debt; at the same time, fewer new doctors owed any money at all, which may be evidence that a growing number of graduates are wealthy enough to self-fund their expensive educations, and that students from less-privileged backgrounds may bear the brunt of the profession’s collective student debt load. American doctors can expect to make high salaries, depending on their specialties, but the prospect of enormous student debt could still deter lower-income students from entering medical school at all. Debt cancellation would level the field.

Despite its issues, Warren’s proposal is more radically progressive than Sanders’s College for All Act, which he introduced in 2017. Sanders’s bill would eliminate public college tuition, but it proposed refinancing student loans and returning interest rates to pre-2006 levels in lieu of full debt cancellation. As a candidate, he has yet to introduce an updated college-affordability proposal. But when he does, he’ll be judged by the standard Elizabeth Warren just set.