One night in early April, roughly 20 of the Democratic Party’s highest-profile donors from the financial industry sat down over dinner to discuss how exactly they were feeling about the 2020 presidential race. For the most part, it wasn’t great.

Convened by two veterans of liberal fund-raising — investors Steven Rattner and Blair Effron — the group had no hard-and-fast agenda except to share notes on the overflowing field of candidates. The crowd of Democratic heavyweights, including Clinton-administration Treasury secretary and Goldman Sachs and Citi alum Robert Rubin, former ambassador to France Jane Hartley, and venture capitalist Deven Parekh, knew most of the contenders well. But coming to some kind of consensus, picking a plausible candidate they felt they could all live with and throw their considerable money behind — that was a far-fetched proposition.

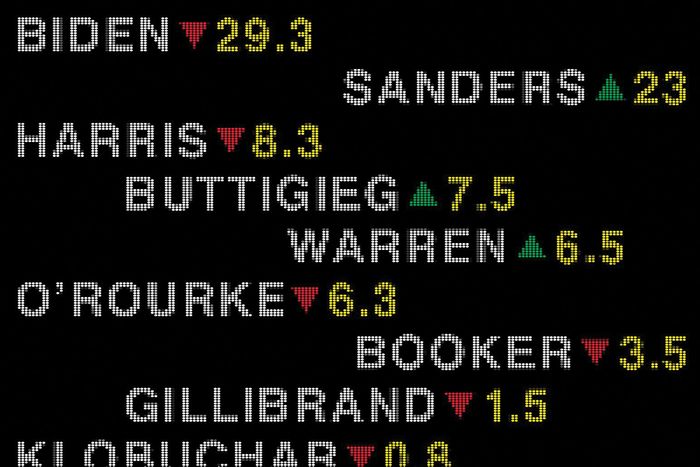

“There’s tremendous fear,” said one banker who was there. The candidates who had long cultivated relationships with Wall Street — such as Cory Booker and Kirsten Gillibrand — were struggling to gain traction and had grown more hostile to finance as their party had, too. Joe Biden, leading in early polls, had a comforting history in the Obama White House and a reputation as an Establishment Democrat but had never, until a few months ago, maintained any meaningful relationship with Wall Street, hadn’t even announced his candidacy yet, and struck many bankers as a dubious bet to beat Donald Trump. Nearly everyone else in the field, the financiers felt, was being pulled leftward by Bernie Sanders (the preposterously well-funded contender they considered too crazy to even imagine in the White House) and Elizabeth Warren (less crazy, Democrats on Wall Street think, and way more competent). “She would torture them,” one banker told me. “Warren strikes fear in their hearts,” explained a New York executive close to banking leaders from both parties — so much fear that such investors often speak of the U.S. senator from Massachusetts, a former law professor and consumer advocate, as a co-front-runner with Sanders. “How do we come up with an alternative?” asked one person at the dinner.

There were a few options, none perfect. Beto O’Rourke had recently launched his campaign, and his congressional record was essentially a centrist-shaped blank slate. Pete Buttigieg was a McKinsey alum who came from the Rust Belt but talked like a Silicon Valley exec or an Obama Treasury official, but no one, yet, took him seriously.

Kamala Harris was a favorite of many in the room. The U.S. senator from California now describes herself as a populist and highlighted a past confrontation with JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon over foreclosures in her pre-campaign book, but in 2012, as California’s attorney general, she passed on prosecuting OneWest and its CEO, Steven Mnuchin. In this cycle, she has been the Democrat perhaps most active in seeking Wall Street money (Citi vice-chairman Ray McGuire and Pine Street partner Brian Mathis are helping with her Wall Street outreach, and she recently headlined a fund-raiser hosted by LionTree CEO Aryeh Bourkoff) and occasionally its advice (BlackRock’s Michael Pyle, an Obama-administration alum, is advising her on economics). “People are generally in search of a candidate who has the right set of views, has the right character, but also can win,” Rattner told me later. “Right now, it is very hard to see who checks all three boxes.”

There was no agreement. By evening’s end, multiple donors walked away planning to write checks to three or four or five candidates — hoping they stay relatively moderate — rather than going all in on any one. Among the committed Democrats on Wall Street, this wait-and-see, as-long-as-it’s-not-Bernie-or-Elizabeth posture has become the norm. “This is like venture investing. You really don’t know who’s going to break out, but your hope is you have a good portfolio and that one of these investments breaks out,” Bruce Heyman, a former Goldman managing director and ambassador to Canada, told me.

Of course, these longtime donors are more committed to the Democrats than the average guy on Wall Street. Two years ago, Trump seemed noxious enough that Democrats (reasonably) hoped to continue growing their considerable advantage over Republicans in the New York finance set. But one GOP-driven tax cut and one leftward shift in the Democratic Party later, a worried handful of bankers is considering turning that story on its head. “They’re too far left! They’re too far left!” said Alex Sanchez, CEO of the Florida Bankers Association.

“I mean, honestly, if it’s Bernie versus Trump, I have no fucking idea what I’m going to do,” one Democratic hedge funder told me. “Maybe I won’t vote.”

Democratic donors aren’t especially worried about policy; few have sussed out where candidates stand on Dodd-Frank or the carried-interest tax loophole, and few believe that, aside from Sanders or Warren, any contenders are likely to make an aggressive new push for regulation as president. What agitates them instead is — in a replay of the alienation they felt during the Obama presidency thanks to a few stray “fat cats” comments — how Democratic rhetoric threatens their sense of status. No moment crystallized the new reality more than when former Colorado governor John Hickenlooper — a centrist candidate who was a prominent business owner in Denver before entering politics — refused to even call himself a capitalist in a Morning Joe interview in March.

Before Trump won, Hillary Clinton had outraised him by a margin of more than four to one among the financial crowd, which had long regarded him as a pariah because of his shady record and bankruptcies. Now? “The anti-corporate, anti–Wall Street direction of the Democratic Party is driving Democrats into the Trump camp, which is, in most cases, the last place they want to be,” said Kathryn Wylde, CEO of the Partnership for New York City, the business group that counts among its members all of the city’s major financial institutions. “The fact that he’s raised as much money as he has is a reflection of how many Democrats are holding their nose and supporting him because they feel demonized by the Democrats.” In mid-April, Trump’s team revealed it had raised over $30 million in the first quarter of 2019, slightly more than the top two Democratic candidates combined. If you add up all the Democrats’ dollars, the challengers are way ahead — but among donors, and indeed among the candidates themselves, the perception remains that the president is accumulating a real edge. Meanwhile, Goldman released its 2020 outlook: Trump, the firm concluded, now has a “narrow advantage.” Even Paul Singer, the GOP hedge-fund magnate who backed efforts to defeat Trump in 2016 — and who funds the Washington Free Beacon, which first paid for the anti-Trump research that later became “the dossier” — stopped by a small Trump fund-raising roundtable in New York late last year. “Well, we must be doing well now that Paul’s here,” Trump said.

“Wall Street for Trump is the reverse Bradley effect,” said hedge-fund manager Anthony Scaramucci, the Republican fund-raiser who (very) briefly served as Trump’s White House communications director, referring to the theory that voters overstate their support for nonwhite candidates in polls. “They all secretly love him, but because of their clients and the polarity, they don’t want to say it out loud.”

Over coffee recently in midtown, an investment pro with a long history in Democratic politics described the struggle to resist the unexpected pull of Trump. “What matters more?” he asked, looking up at me. “My social values or my paycheck?”

It would appear from the outside to be happy days on Wall Street. Banks smashed previous profit records in 2018, taxes were down, stocks were up, and few people in power in Washington were talking about tightening regulations. But the arrival of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez was seen on Wall Street as a tremor portending a broader earthquake on the left. Indeed, there has been no greater mobilizer of wealthy centrists than her primary win in June. In July, a few hundred gathered in Columbus, Ohio, to find a policy platform that would defeat both Trump and Sanders. Another group of investors figured if the parties were now poisoned, they’d just have to draft an independent presidential candidate themselves. It was no secret that John Kasich and Howard Schultz were considering it, and Mike Bloomberg, too. But another option held promise: moderate Virginia Democrat Mark Warner, who’d twice before considered running. The senator agreed to meet last summer and listened as they promised funding and presented a plan to get his name on the ballot in all 50 states. Then Warner, assessing the probability of a successful third-party run, told them, “Thanks, but no thanks.”

Meanwhile, parts of the Democratic field were doing the same, with most candidates focused on building Sanders-style small-dollar, email-driven fund-raising machines. (Sanders raised $10 million that way in just his first week as a candidate.) “It’s kind of stunning how a bunch of these people running for president haven’t gotten ahold of [a list of top past contributors] and said, ‘What can I do to get this person?’ ” fumed a hedge-fund honcho out of the loop for the first time in two decades. “It’s sort of basic political IQ.”

“Everyone wants to seem relevant,” one prominent investor told me. But for the first time he or any of his friends could remember, “we’re just not fucking relevant. We’re not that big of a deal anymore. None of us!”

“A lot of the donor community is worried about losing their presidential perks and ambassadorial gigs to baristas,” said veteran New York Democratic fund-raiser Robert Zimmerman. “It’s long overdue.”

Those candidates still reaching out to Wall Street have mostly done so underground, visiting the homes and offices of wealthy donors while adamantly demanding secrecy — at least seven candidates privately auditioned for a group of 16 leading Obama donors in D.C. in February. The memory of Sanders supporters derisively showering Clinton’s motorcade with dollar bills as it drove into George Clooney’s home for an expensive 2016 fund-raiser remained particularly searing. Morgan Stanley managing director Tom Nides, a deputy secretary of State under Clinton (and a friend of Minnesota senator and 2020 Democratic presidential candidate Amy Klobuchar’s since they interned for Walter Mondale together), last year hosted a handful of likely candidates for a series of private dinners with potential supporters. But no bank has set up any meet-and-greets like the ones then-Senator Obama lit up in 2006. For the first time, campaigns have started sending out invitations to formal private fund-raising events without either the hosts’ names or the entry price printed on them, just in case they leaked. “They don’t want to get Bernied,” said a former bank executive.

Not everyone is playing the same game. When he left the vice-presidency, Biden — historically a lousy fund-raiser, with threadbare finance ties beyond Delaware’s credit-card industry — established a network of post–White House organizations and took care to stack them not just with longtime aides and friends but with Wall Street’s Democratic heavy hitters. Last spring, he installed a policy advisory board for the new Biden Institute at the University of Delaware, including JPMorgan’s Peter Scher, KeyBank’s Don Graves, former Treasury secretary Larry Summers, and onetime Goldman investor Eric Mindich. Now, said one top party fund-raiser in New York, “there’s a lot of praying for Joe Biden.”

But some high-flying former Obama fund-raisers who witnessed Biden at the former president’s side worry about his prospects against Trump. For them, there was Beto. In considering a run, O’Rourke consulted with former top political aides to Obama, such as David Plouffe, but as his own decision deadline neared, he started picking the brains of a handful of Obama’s top-tier donors and bundlers. One, private-equity exec Mark Gallogly, became convinced O’Rourke was the young inspirer needed to lead the anti-Trump movement and flew to meet with the congressman and his family. Investment banker and former ambassador to the U.K. Louis Susman, meanwhile, also jumped onboard, making calls across Wall Street to construct a fund-raising operation for him. “He will probably raise more money than any candidate in the history of our presidential politics, and he will do so not just with large donors but with more money [from donations of] under $500 than anyone in our history of presidential politics,” predicted Gilbert Garcia, a Houston investor. “A lot of senior people are going to get involved. You had a lot of senior people get involved for Obama. You’re going to see that effect.”

Nearing launch day, O’Rourke reciprocated. In calls with potential supporters, he asked for advice, and hours before making his campaign official, he rang Robert Wolf, the former UBS chair. He had no specific ask, he said — he’d just heard Wolf was a good person to know for the road ahead. When he did announce, on a Thursday morning in March, Biden’s top lieutenants, led by right-hand man Steve Ricchetti, made a round of calls to top potential supporters that afternoon to head off the threat.

Now Biden has his team, O’Rourke his, and Harris hers — with power bases in California and New York. If you were one of the 100 campaign bundlers who’d attended Harris’s private New York City finance kickoff earlier this year, her team presented you with an ask: to commit to raise $27,000 each in the first quarter of the year. But when the quarter ended, you also saw the team’s publicly shared numbers; of the $12 million she raised, more than half came from online sources, where her average contribution was $28. Those figures reinforce the lesson of Sanders’s kickoff and O’Rourke’s $6.1 million day one: Big in-person fund-raising events have, in many cases, gone out of style, and many big-money donors are still playing wait-and-see. Others have pushed Michael Bennet, the senator from Colorado, and Mitch Landrieu, the former mayor of New Orleans, to enter the race. Earlier this year, 105 of the party’s most in-demand donors convened in south Florida for a private retreat to consider their next investments. Veteran Democratic strategist James Carville addressed the group over dinner and asked who among them had committed to a presidential candidate. Just four hands went up.

But on a recent morning in Manhattan, a handful of Wall Street’s Democratic power brokers got to chatting after a breakfast fund-raiser for a congressman. The topic was unavoidable: In recent weeks, a new name had entered the fold. Now, as the donors spoke, more news trickled out. A growing array of influential bundlers in the finance world had made their choice to support the new entrant, even though many had planned to stay neutral far longer. Hedge-fund manager Orin Kramer, for one, was onboard after meeting the candidate in person a few weeks earlier. David Jacobson, the onetime ambassador to Canada who is now a BMO vice-chairman — and who helped organize the auditions in February — was too. And Steve Elmendorf, a D.C. lobbyist who has worked closely with Wall Street leaders for years, made his choice. He even changed the background of his Facebook page to match the moment: It’s now a wide shot of a large crowd looking up at a stage with a massive PETE 2020 sign staring back.

*This article appears in the April 29, 2019, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!