Three years ago, National Review famously published a special issue titled “Against Trump,” denouncing the Republican front-runner as a con man unfit for office. Its latest issue has a theme much less likely to offend the magazine’s base of subscribers and donors: “Against Socialism.” That the flagship organ of American conservative thought opposes socialism should come as no surprise. What the issue does help explain is the magazine’s progression from “Against Trump” to “Against Socialism,” and why its famously heretical step is unlikely to be repeated.

In a short introduction, editor Rich Lowry explains the motivation. “In the 1990s, Bill Clinton operated within the broad economic consensus established by Ronald Reagan, and when Republicans called Barack Obama a socialist, some on the left considered it a racially charged smear. But here we are: A self-avowed socialist nearly won the Democratic nomination in 2016 and is a serious contender this time. Another socialist, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, is the hottest thing in progressive politics today.”

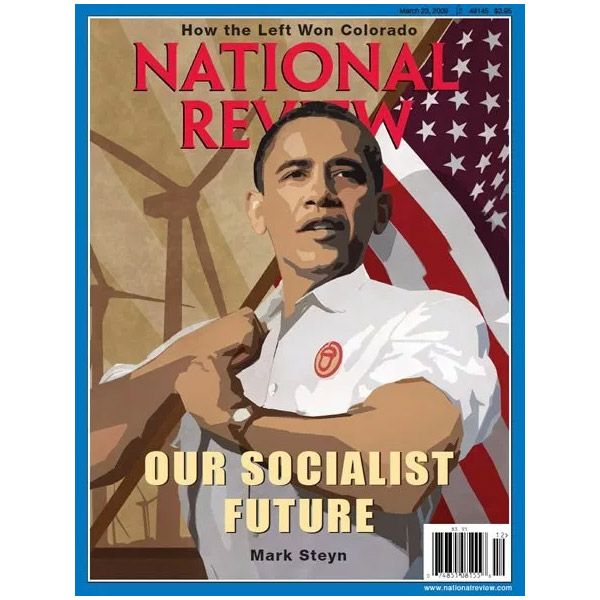

National Review was hardly shy about charging previous Democrats with socialism, either. Obama was the subject of NR’s previous spate of loud warnings of impending socialism. Authors like Dinesh D’Souza, Stanley Kurtz, and Andrew McCarthy all regaled National Review readers with lurid tales of Obama’s alleged secret ties to the Marxist netherworld. A 2009 cover story warned, “Most Americans don’t yet grasp the scale of the Obama project … we’re all doomed. And by ‘doomed’ I’m not merely making the usual overheated rhetorical flourish in an attempt to persuade you to stick through the rather dry statistics in the next paragraph, but projecting total societal collapse and global conflagration, and all sooner than you think.”

A better title for National Review’s new anti-socialism package might have been, “Socialism: This Time, We’re Actually Not Making It Up.”

It is true, as Lowry observes, that socialism has entered the political debate as a positive creed, not just as a smear tossed about by the paranoids and grifters of the right. As a long-standing adherent of mixed-economy liberalism, I’m receptive to critiques of socialism. NR’s package makes little effort to distinguish between real socialism and the mixed-economy liberalism that NR so frequently called socialism. Perhaps because National Review cannot confess its tradition of red-baiting liberals since the days of Joe McCarthy, an ally of the magazine, it is largely bereft of engagement (even of the most critical kind) with its putative subject matter.

Analyzing the specifically socialist character of Sanders or Ocasio-Cortez’s ideology would require conceding they’re different than the liberal ideology of most Democrats. (Such as House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, who has repeatedly spoken for the party by insisting “we’re capitalist” and socialism is “not the view” of the party.) Acknowledging the tension between the Democrats’ dominant capitalist wing and insurgent socialist faction would, among other things, undermine the Republican messaging operation which is premised on conflating the two.

Rather than explaining what the new socialism stands for, various essays wander off on rants against unrelated branches of the left-wing tradition. While the issue does, this time, contain actual socialists, it does not contain many actual members of the Democratic Party. A historical review of Soviet communism by Joshua Muravchik concedes in passing, at the very end, “Of course, not all socialists followed the bloody trail Lenin blazed. Some, usually under the banner of parties calling themselves ‘labor’ or ‘social democratic,’ insisted on pursuing only democratic and peaceful paths” which “led no farther than the welfare state undergirded by a capitalist economy.” But since Sanders and his supporters in Congress are social democrats, and not Marxist revolutionaries, this means the entire remainder of Muravchik’s essay is irrelevant to the subject that putatively inspired it.

The same problem occurs in a Kevin Williamson essay. After hundreds of words denouncing a centrally planned economy, it allows this small aside: “The Nordic social democracies so dear to the self-styled socialists of the United States mostly have been divesting themselves of state enterprises.” In other words, the “self-styled socialists of the United States” reject the model that every other sentence in his essay is devoted to denouncing. After the reader is promised an issue devoted to countering the ideas of a rising faction in the Democratic Party, Muravchik and Williamson quietly admit that they are arguing with a completely different faction that has no important adherents in the United States.

A more relevant and illuminating argument can be found in another essay, by Charles C.W. Cooke. Cooke’s subject is not socialism, but (though he fails to use the term) economic democracy. Cooke argues that democracy, properly understood, does not allow the voters to make any decision they want on economic policy. Democracy and the Constitution require small government.

Cooke is frustratingly vague about exactly how small the government must remain in order to satisfy this definition of democracy. Is universal health insurance undemocratic? A $10 minimum wage? $15? He does not say. Cooke leaves a hint at the answer when he describes the proper, democratic level of taxation: “Keeping the lion’s share of the fruits of your labor is, itself, a democratic act.” Later, he specifies “lion’s share” as a universal right to a total tax rate below 50 percent, and equates it with rights like freedom of speech, religion, the right to representation, and so on.

Of course, this means that a large number of European countries, which tax their richest citizens at over 50 percent effective rates, are not democracies by Cooke’s definition. But I don’t think he would consider this fact a problem for his thesis. Cooke also lists “the right to bear arms” as one of these fundamental human rights that “6,000 years or so of human civilization” has shown is essentially to human liberty; since the United States is the sole major democracy to allow almost completely unfettered access to military-grade firearms, this would disqualify nearly all the world’s other freely elected government from “democracy” as he defines it. Cooke’s argument tells us very little about socialism, unless you define socialism to mean every country other than the United States. It tells us a lot about conservatism, especially its virulently anti-statist American variety.

Cooke is hardly the first thinker on the right to argue that freedom means more than just a set of political rights. It is a long-standing theme on the American right. Conservative parties in most advanced democracies have made their peace with a larger welfare state, but American conservatives have never relinquished their conviction that the entrenchment of the New Deal is not only suboptimal but fundamentally undemocratic. Milton Friedman argued, “economic freedom” — i.e., small government — “is an end in itself.” National Review’s Jonah Goldberg recently endorsed this idea, arguing “markets are not just a tool” but instead “an inalienable right.”

This belief explains why American conservatives have fiercely and even hysterically attacked every advance of the safety net and the regulatory state, from the abolition of child labor to Social Security to Obamacare, as not merely unwise but as struggle to death to snuff out liberty itself. They believe more than mere fractions of GDP growth is at stake with every advance of government. They truly and genuinely believe that freedom rests upon victory over seemingly mundane questions like a few points added to the top tax rate. Conservatism at its core is a fear that democracy enables the majority to redistribute income from the rich.

More pertinently, this belief on the right also explains why even conservatives who greeted Trump with perfect horror and recoiled at his demagoguery and and authoritarianism have settled in to defend him. To liberals and moderates, it seems myopic in the extreme to weigh the merits of Trump’s fleeting policy victories on taxes and regulation over his utter contempt for democratic norms. To conservatives, the policy victories amount to a large part of what they define democracy to be. It may not exactly be “democratic” for the president to order government retribution against critical media outlets, or to be legally permitted to obstruct any investigation the president considers unfair. But from the conservative standpoint, these flaws balance against what they count as large advances for democracy in the form of tax cuts, deregulation, and judges likely to strike down future regulations and social-welfare programs.

This view explains why the House Freedom Caucus, an organ devoted to small-government fanaticism, condemned Representative Justin Amash for endorsing Trump’s impeachment. It would also explain why National Review is running an advertisement for donations called “We’ve Had Bill Barr’s Back.” It itemizes no less than 35 pieces in the National Review defending Trump’s attorney general, whose willingness to placate a president who has pure contempt for democratic norms and the rule of law has made Republicans who care about those values recoil in horror.

In 2016, National Review warned against Trump’s “strong-man overtones” which were “anathema to the ordered liberty that conservatives hold dear.” Those fears have been fully realized.

The conservative movement’s embrace of Trump has puzzled so many outsiders as a betrayal of principle. Cooke’s essay makes clear that, on the contrary, their support for the plutocrat-in-chief is a vindication of conservative principle: Strongman government in the pursuit of oligarchy is no vice.