From the beginning of American history all the way through Veep, the role of vice-president has often been mocked and ridiculed, even by vice-presidents themselves. But as Jared Cohen makes clear in his new book, Accidental Presidents: Eight Men Who Changed America, some running mates who might otherwise have been consigned to the dustbin of history ended up changing the course of American history, for better — and in many cases worse — after their bosses died or were killed in office. In the book, Cohen, who has advised Condoleezza Rice and Hillary Clinton and is now the CEO of the technology company Jigsaw, explores the often-overlooked consequences of vice-presidential ascension, from Millard Fillmore’s pivot on the Compromise of 1850 to Harry Truman’s World War II decisiveness. Intelligencer spoke with him about which veeps managed the transition to actual authority best and whether the job of vice-president even makes sense in 2019.

I had no idea that John Tyler, who is so little remembered, was such a presidential-succession trailblazer. When William Henry Harrison died a month after taking office, Tyler insisted that he be treated fully as the president, even though there was really no clear language on that question in the Constitution and there wouldn’t be a hard-and-fast rule until the 25th Amendment passed in 1967. Looking back on all these vice-presidents, many of whom didn’t do so well in the top job, do you think that Tyler’s consequential decision ended up being the right way to go?

John Tyler’s a really complicated character because, on the one hand, he addressed the real vulnerability in the Constitution by being assertive and setting a precedent that held all the way through Lyndon Johnson. We forget: Johnson becomes president in 1963 based on an action that Tyler takes in 1841.

In reading the Constitution and knowing how the Founding Fathers thought about the vice-presidency, my feeling after researching and writing this book is that they didn’t intend for the vice-president to become president — just to discharge the duties of the presidency.

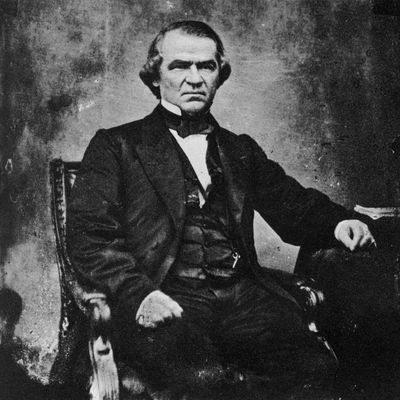

But I think that, as the republic evolved, and perhaps because of what Tyler did, we moved in a direction where we became much more comfortable with that idea. I say this in the book — it’s a testament to the Tyler precedent that, when Zachary Taylor died in 1850, nobody questioned whether or not Millard Fillmore is the president. But you start to do the counterfactuals, and you look at what a disaster Andrew Johnson was and the devastating impact that his presidency had on civil rights, and you kind of wish Tyler hadn’t done that.

Another thing I didn’t quite realize is that Johnson seemed like an eminently reasonable vice-presidential pick at the time Lincoln chose him. But as you say, his tenure was a disaster. Is he the starkest example of a vice-president whose presidency went off the rails?

It would be tempting to say presidential succession has been a mixed bag, but you can’t say that, because Andrew Johnson really was such a catastrophe, right? You think about the consequences for civil rights, which are consequences we’re still living with today.

Back then, the presidential candidate didn’t choose their running mate, but 1864 was such an important election that Lincoln plotted this sophisticated, behind-the-scenes decision to swap Hannibal Hamlin with Johnson, mainly because he needed a War Democrat from a border state. Johnson was pretty well respected in the North, but was the only southern senator to stay loyal to the Union. He had a lot of unique attributes, and Lincoln was desperate to win the election.

When the Confederate states seceded from the Union, all Johnson cared about was putting it back together. So he made a decision that, despite his personal beliefs, he would stay loyal. He thought the best way to destroy the Confederacy was to destroy its leadership and to destroy the whole system, which meant punishing all the traitors in the most ferocious way and breaking its economic backbone, slavery. His rhetoric on civil rights and punishment of traitors, which was driven by tactics as opposed to morality, was more aggressive than even Lincoln, which is why, when Lincoln died, the Radical Republicans think they have one of their own in the White House.

Their expectations came crashing down when the Civil War ended, and Johnson basically left civil rights to the states and gave amnesty to the entire leadership. I think part of the reason that Congress accelerated impeachment proceedings, and went after him beyond his obstructionist measures around Reconstruction, was that they were so furious that this man who they thought was like-minded Radical Republicans proved to be the exact opposite.

Of the eight examples in the book, you only rate two vice-presidents as being really successful after their bosses died: Theodore Roosevelt and Harry Truman. What do you think distinguishes them from the others?

I think that they’re really different characters. In the case of Roosevelt, he’s the only one of these men who probably would’ve been elected president eventually anyway, so he’s the only one other than maybe Lyndon Johnson who had spent any time thinking about the role. Johnson’s time had passed by the time he became vice-president, but Roosevelt salivated over the possibility of becoming president.

When McKinley died, Roosevelt says that it’s a terrible thing to come into the presidency this way, but it would be far worse to be morbid about it. He was a force of nature and quite irrepressible, so I think it was just sort of sheer character and will that made him successful. He was ready to lead on day one, not because he prepared as vice-president, but because he’d been preparing his whole life.

In the case of Harry Truman, he’s the most successful of all the accidental presidents, in part because he’s so unexpected. In 1944, all the Democratic Party bosses know FDR is a dying man, and they can’t stand the idea of Henry Wallace on the ticket because he was seen as a Soviet sympathizer and too liberal. So they throw Truman onto the ticket, really as an anti-Wallace candidate. Nobody really gives much thought, including Truman, to the prospects of him becoming president. In 82 days as vice-president, he only meets FDR twice, doesn’t get a single intelligence briefing, doesn’t get briefed on the atomic bomb, doesn’t step foot in the Map Room where the wars are being planned.

Then on April 12, 1945, FDR dies, and Truman faces enormous challenges, from the Battle of Okinawa raging in the Pacific to Stalin reneging on his promises from Yalta, to having to figure out what to do with this destructive atomic weapon. Hitler’s still running things from a bunker in Germany, and Truman he has to make some of the most important decisions in his first four months. Never has a man been so less prepared for a more seminal moment in history than Harry Truman, and yet he rises to the occasion.

In the case of Johnson, he went in alone and defied everybody. In the case of Truman, he found the right balance between being decisive and listening to men like Dean Acheson and George Marshall. They very easily could’ve looked at Truman and said, “He’s not FDR” and been dismissive of him, much like the Kennedy men were of LBJ, but they decided the future of the world rested on Harry Truman being successful, and they were going to make him successful.

The job of vice-president has been seen by many as basically useless for a long time, notwithstanding Dick Cheney’s reign. And there are still all these perverse incentives at work in terms of who a candidate chooses to be their running mate. President Trump picked Mike Pence to appeal to Evangelical voters, with probably little thought as to whether he would be a good president. Right now, we’re reevaluating a lot of the cornerstones of our democracy from the Electoral College to the size of the Supreme Court. Do you think the vice-presidency actually makes sense as a job in 2019?

I think there’s two questions in there. One is: Does the office of the vice-president makes sense? I actually think, in modern times, it makes a lot more sense than it did, because the president used to be a much more contained role. Historically, the president didn’t travel. If you think about how much of a global role the president plays now, just the breadth of foreign-policy issues, I think having a vice-president who can stand in for the president and be in more places is actually quite important. Not to mention the role that the VP plays as presiding officer and tie-breaker in the Senate.

But it’s only a useful role if the vice-president is fully integrated into the administration so that, should the unthinkable happen, they can be ready to lead on day one.

With Mike Pence, the question isn’t about policy. You can agree or disagree with his policies. What makes me comfortable is that Pence is in the loop and integrated into the administration on both foreign and domestic matters. He would be ready to lead on day one because he knows what’s going on. That’s been the case for the last several vice-presidents, going all the way back through George H.W. Bush. So you’d be tempted to say, “Okay, we figured this out and everything works well now.” But then you have to account for the fact that John McCain selected Sarah Palin in 2008. Had he won the election, it’s very hard to imagine that playing out in a way where she would’ve been fully integrated into the foreign and domestic policies of a McCain administration.

This is to me the big lesson of the accidental president: Of the eight vice-presidents who became president when their predecessor died, not a single one of them was integrated into the administration. Not a single one of them, except maybe Calvin Coolidge, enjoyed a good relationship with their predecessor. In a number of cases, it was a venomous relationship. None of these men were ready to lead on day one, and most of these men departed dramatically from their predecessor’s policies.

When Zachary Taylor died, Millard Fillmore gets around the obstacles of the Compromise of 1850. When Lincoln died, you get Andrew Johnson’s vision of reconstruction instead. I don’t think anyone would argue that Roosevelt and McKinley had different mind-sets when it came to policy. I think if you look at Truman, Truman was much less trusting of Stalin than FDR was. If you look at LBJ, I don’t think that if Kennedy had survived, you would’ve had the Civil Rights Act in 1964.

To go back to the other part of your question, if you think about how we select vice-presidents, the big issue here is that the presidential candidate really has the sole discretion about who they run with, What that lends itself toward is a situation where you’re up against the ropes and you hit a particular bump in the polls in a particular week at a particular stage in the election …

We treat the selection of a vice-president as an electoral mechanism for a particular moment, rather than somebody who we think can lead the nation. Wisdom suggests that you don’t want to pick somebody who can outshine you, and you don’t want to pick somebody who’s going to embarrass you. So what that lends itself to is kind of the like the JV version of yourself. My problem with that is I don’t want the JV version of the person at the top of the ticket to one day become president.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.