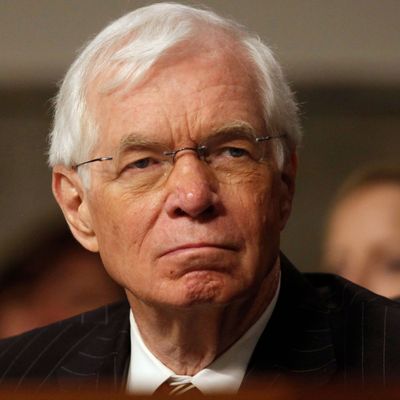

With the death of long-time U.S. senator Thad Cochran of Mississippi, who served from 1979 until his health-related retirement last year, another fragile link to a bygone era of American politics has been severed. Many current observers of the political scene, particularly progressives, tend to view today’s solidly Republican South purely as a product of racial realignment. Following the Jim Crow era, the GOP replaced southern Democrats as the White Man’s Party, while newly enfranchised African-Americans gravitated to an increasingly liberal and diverse Donkey Party. But some southern Republicans like Thad Cochran reflected an older, pre–civil rights set of motives for leaving Democrats behind.

As Sean Trende pointed out in a data-laden essay back in 2010, there was a pre-Goldwater, pre-Reagan southern Republican Party that may have included many racists, but was not primarily motivated by white racial fears and resentments. There was a species of Mountain Republicanism in the Appalachian and Blue Ridge regions that dated all the way back to the Civil War. Tennessee’s Lamar Alexander (retiring from the Senate next year) was born into that heritage. There were also a growing number of urban-suburban upscale business types who gravitated to the GOP, particularly during the Eisenhower years, for reasons much like their counterparts in other parts of the country. Johnny Isakson of Georgia (who is likely to retire at the end of his current term in 2022) and Cochran are arguably representatives of that legacy.

According to his own account, Cochran, who wasn’t that politically active in his youth, became estranged from the Democratic Party not over LBJ’s drive for civil rights but because of his stewardship of the Vietnam War. He supported Richard Nixon for president in 1968 even as most white Mississipians voted for segregationist independent George Wallace (Wallace won 64 percent of the vote, Nixon just 14 percent).

Those unfamiliar with the rapidly shifting tides of southern politics in those years might have trouble distinguishing Cochran’s drift into the GOP from the move of others drawn to the party for primarily racial reasons. You need look no farther than his longtime Senate colleague Trent Lott. As a student at Ole Miss several years after Cochran’s arrival there, Lott stood out as a passionate defender of segregated fraternities. He cut his teeth in politics as top aide to Gulf Coast congressman William Colmer, a classic old-school Democratic segregationist of the breed often called “Dixiecrats.” When Colmer retired in 1972, Lott ran for his seat as a Republican with the old bigot’s blessings — in the same year Cochran was elected to the House from a traditionally more moderate Jackson-based district. The two men spent decades as colleagues and sometimes rivals in the Senate. But it wasn’t really that surprising when Lott came to grief in 2002 for talking about how much better life would have been had Dixiecrat Strom Thurmond been elected president in 1948. Neither was it surprising that in his last political campaign in 2014, Cochran was saved by African-American voters who valued his role in directing federal largesse to his state.

Cochran, you may recall, was on the ropes after neo-Confederate tea-party favorite Chris McDaniel ran ahead of him in a GOP primary and forced a runoff. Then Cochran did something unheard of in southern Republican politics, as Josh Kraushaar explained:

During the runoff, Cochran made overt appeals to the state’s sizable African-American electorate, including several television ads featuring the senator campaigning with black voters. The New York Times reported that the leading pro-Cochran super PAC, Mississippi Conservatives, paid African-American leaders to get out the vote for the senator in the runoff.

In Mississippi, the electorate is more racially polarized than any other state in the country. African-Americans make up about one-third of the state’s voters and they are overwhelmingly Democratic. In 2008, a whopping 98 percent of African-Americans supported President Obama, while only 11 percent of whites supported the president that year. African-American turnout in a Republican primary is a very rare occurrence.

It worked, as Cochran won the runoff, leaving McDaniel and many other southern conservatives to complain bitterly that the incumbent had broken an unwritten rule by drawing “Democrats” (i.e., black voters) into the starchy white sanctuary of a GOP primary.

Cochran’s heresy was the most audacious tactic in intra-southern-Republican politics since Johnny Isakson dared publicize his pro-choice views on abortion in a 1996 Senate primary, which he proceeded to lose. Unsurprisingly, Isakson is now a 100 percent anti-abortion senator, and Cochran’s gone. You could say that the national GOP has changed as rapidly as its southern wing; Cochran, after all, joined a Senate Republican Conference when he arrived that included unimaginably liberal figures like Jacob Javits, Mac Mathias, Mark Hatfield, Lowell Weicker, John Chaffee, and Chuck Percy. But it was the South that led the ideological realignment of the Republican Party to the hard right.

None of this is to say that all surviving southern Republican officeholders are racists, though their near-universal and increasingly noisy support for Donald Trump is a depressing sign of anti-anti-racism, at the very least. But it is reasonably clear that of the various streams that contributed to the pro-Republican tide in the South, it’s the dirty racial waters that shaped the new White Man’s Party most decisively. Maybe that will change some day as Republicans in the South and elsewhere finally decide that expanding their base is a matter of survival. Perhaps then Thad Cochran will be remembered for something more profound than his skill in shaking the appropriations tree for his constituents.