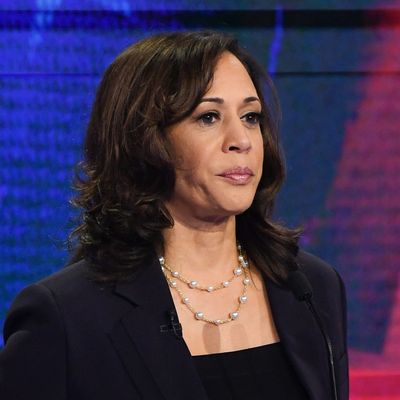

“I’m going to now direct this to Vice-President Biden,” said Senator Kamala Harris at Thursday’s primary debate. “I do not believe you are a racist and I agree with you when you commit yourself to the importance of finding common ground. But, I also believe — and it’s personal … [It] was hurtful to hear you talk about the reputations of two United States senators who built their reputations and career on segregation of race in this country. And it was not only that, but you also worked with them to oppose busing.”

Harris was referencing Joe Biden’s remarks last week where he cited his “civil” relationships with James O. Eastland and Herman Talmadge — both segregationists and fellow Democratic senators at the time — as an example of his ability to find common ground with ideological foes. She was also illustrating how that common ground underscored a set of shared priorities: Biden was against busing black and white children out of their neighborhood schools to integrate them, an effort the former vice-president has dismissed as “asinine,” “bankrupt,” and “a liberal train wreck.”

Of those onstage, Harris was the best-equipped to confront him, in part because she was bused herself. “[There] was a little girl in California who was part of the second class to integrate her public schools and she was bused to school every day,” Harris said. “And that little girl was me.” It was a memorable anecdote that laid bare the human costs of racist ideology and policy, and Harris’s campaign was quick to capitalize, tweeting a childhood photo of her and selling T-shirts featuring the image. But it also diverged from the conciliatory pose that black candidates have typically been compelled to strike when confronted by racism during their campaigns. In the past, Biden has benefited from this impulse. No more.

Biden’s record on key civil-rights matters like school integration and incarceration have long been viewed as a liability for his 2020 ambitions. He is sustained partly by name recognition and his affiliation with the first black president, Barack Obama, and holds strong polling leads among primary voters generally and black voters especially. His pitch — which much of the electorate seems to cosign — is that he is the most “electable” candidate the Democrats have to offer: a seasoned politician who can recapture the white Rust Belt swing voters who propelled Trump to victory in 2016. This standing is not unearned. Biden was a beloved vice-president under a beloved commander-in-chief, and as a senator voted to preserve or advance voting rights and affirmative action.

But he has also been prone to racist remarks and backing racist policy, including authoring the 1994 Crime Bill and implementing asymmetrical legal consequences for crack-related crimes compared to those involving powder cocaine. Nevertheless, Biden can attribute many of his professional high points to black voters and politicians willing to overlook the stains on his record to advance their own goals. This is not an alien dynamic in politics, but has manifested in particular ways with black candidates. Obama predicted early on the anxiety that his historic candidacy might prompt. His eventual presidency was a testament to the moderation he practiced while running — marked by a hesitancy to draw attention to racism, and when he did, an emphasis on how Americans of all backgrounds have united to overcome it, rather than how white people have exacerbated it.

Obama’s approach was by turns conciliatory and tacitly exonerative. He was careful to avoid both Biden’s voting record and using as a cudgel the then-Delaware senator’s suggestion, in 2007, that he was “the first sort of mainstream African-American who is articulate and bright and clean and a nice-looking guy.” “I didn’t take Senator Biden’s comments personally, but obviously they were historically inaccurate,” Obama said at the time. “African-American presidential candidates like Jesse Jackson, Shirley Chisholm, Carol Moseley Braun, and Al Sharpton gave a voice to many important issues through their campaigns, and no one would call them inarticulate.”

Jackson echoed Obama’s remarks, saying of Biden’s, “It was a gaffe. It was not an intentional racially pejorative statement. It could be interpreted that way, but that’s not what he meant.” Both men might have been truly unbothered, but they also doubtless understood the perils of dwelling on such a combustible issue with a Democratic presidency on the line. The pragmatic wisdom of Obama’s decision became clear the next year when he chose Biden as his running mate. By letting go of the slight, he left the door open for a partner who could both assuage the concerns of voters wary of his youth and inexperience, and reassure conservatives that his presidency was not a precursor to black revolution. In helping Biden, Obama helped himself.

The former vice-president is less useful to Kamala Harris. She needs to beat him and faces an uphill battle to do so. If early analysis is indicative, her exchange with Biden was the debate’s signature moment and helped her standing. Even so, going after the former vice-president was also a gamble on whether voters are willing to embrace a black candidate who so openly confronts her white opponents about their racist complicity. Obama’s success hinged on studiously avoiding this approach. Harris is banking on a more receptive electorate. Public sentiment seems poised to affirm her, at least in the primary: Democrats are far more likely than Republicans to believe America has not gone far enough to achieve racial equality, according to Pew. Live polling of Thursday’s debate showed black voters responding favorably to Harris’s busing remarks.

On the other hand, they also responded favorably to Biden’s retort touting his civil-rights record. Not to mention that although the word “segregation” has accrued negative currency, busing remains broadly unpopular today. This could be immaterial to Harris’s cause. Biden’s polling dominance could be a self-fulfilling prophecy that paves his path to the nomination regardless of what he does. Plenty could change before the first votes are cast in February. But if nothing else, Thursday marked a departure from a long-standing norm. Harris’s remarks were acutely lacking in the kind of trepidation that defined past campaigns, namely Obama’s. The wages of racist policy have rarely been invoked with such precision by a black candidate to indict a white opponent. Whether it was prudent remains to be seen. But it was a long time coming.