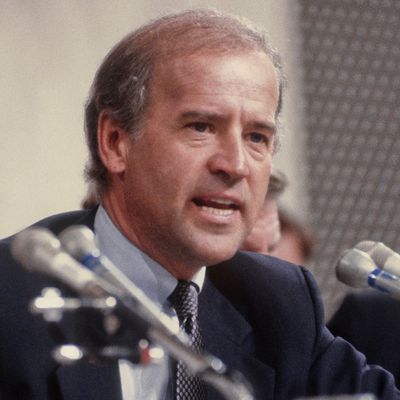

There are two story lines about Joe Biden’s long Senate record that are potentially dangerous for him, in that they could threaten his currently strong support among African-Americans. One involves his friendships with segregationists in the Senate — notably James Eastland, Strom Thurmond, and Herman Talmadge — which he can’t seem to stop talking about. And the other is his responsibility for policies that have led to mass incarceration, including the landmark 1994 crime bill.

What could be happening now is that the two stories are converging, as reflected in a New York Times report on how Biden worked closely with his racist colleagues to push crime policy toward mandatory minimum sentences and other “get tough” positions, long before the 1994 bill.

Mr. Biden finally landed a seat on the judiciary panel in February 1977, and wrote to Mr. Eastland again, petitioning to be put in charge of the subcommittee overseeing prisons and sentencing. By year’s end, with Mr. Eastland’s support, he was pushing to narrow judicial discretion by creating a commission to set “presumptive sentences,” and to eliminate pardons and parole. His aim, he told his hometown newspaper, The Wilmington Evening Journal, was to keep defendants “who don’t meet the middle-class criteria of susceptibility to rehabilitation” from being set free.

In 1981, when Democrats lost the Senate, Republicans installed another old bull Southern segregationist as chairman: Mr. Thurmond, a Democrat-turned-Republican from South Carolina, who had run for president in 1948 on the Dixiecrat platform. Mr. Biden became the ranking Democrat on the committee.

Over the next decade — first with Mr. Thurmond as chairman and then Mr. Biden after Democrats won back the Senate in 1986 — the pair wrote roughly a half-dozen crime bills together, laying the groundwork for three of the most significant pieces of crime legislation of the 20th century: the Comprehensive Crime Control Act of 1984, establishing mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses; the 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act, which dictated much harsher sentences for possession of crack than for powder cocaine; and the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, a vast catchall tough-on-crime bill.

So the 1994 bill wasn’t in any way a departure for Biden. As my colleague Eric Levitz observed earlier this year, the Delaware senator often tried to get to the right of Republicans on crime:

[A]s with busing, Biden was one of the first liberals to discern the rightward shift in public opinion on criminal justice — and quite possibly, the most enthusiastic convert to the gospel of law-and-order liberalism …

In 1989, George H.W. Bush gave a national address outlining his plans to ramp up the war on drugs. Biden delivered the Democratic response, and savaged the Republican’s plan to drastically increase incarceration for drug crimes — from the right.

“Quite frankly, the president’s plan is not tough enough, bold enough, or imaginative enough to meet the crisis at hand,” Biden told the American people. “In a nutshell, the president’s plan does not include enough police officers to catch the violent thugs, enough prosecutors to convict them, enough judges to sentence them, or enough prison cells to put them away for a long time.”

It’s true that as crime rates peaked in the late 1980s and early 1990s, support for major anti-crime measures, including the “war on drugs,” split the African-American community and its political representatives. But Biden seemed more concerned with propitiating tough-on-crime sentiment among his white constituents — and indeed, the Democratic Party’s white constituents, whom they were battling to keep in line, as the Times report notes:

In … Senate floor speeches in 1993 and 1994, Mr. Biden spoke openly of wanting, as Mr. Clinton did, to rid Democrats of their reputation of being soft on crime. Mr. Biden presented the moment as a political window long overdue.

“One of the things I want to do, in addition to end the crime, is end the political carnage that goes on when we talk about crime,” Mr. Biden said. “This is one of these issues that I hope, after this bill, will be moved out of the gridlock category and into an emerging consensus.”

That never happened, but Biden was typical of Democrats of that time who wanted to “neutralize” crime as an issue that Republicans used against them. I can testify to the temptation: In 1994, my then boss, Georgia governor Zell Miller, decided to get to the right of Republicans on crime in the middle of a tough reelection contest by proposing a “two strikes and you’re out” mandatory lifetime sentence for serial offenders. It’s not much of a defense for this demagoguery to say that Miller would have traded pretty much anything to get his way on higher education spending, his great passion. He didn’t care about crime policy. But Joe Biden did. And it’s his leadership — not his support — for law-and-order initiatives that segregationists embraced that poses a potential problem for him today.

Perhaps none of this will ultimately matter to African-American voters, who often reflect their Evangelical religious roots by rewarding late-career conversions to the cause of racial justice. There’s a reason southern white Democratic presidential candidates like Bill Clinton and Jimmy Carter had especially strong African-American support when they ran for president. And it’s worth remembering that Biden himself was a strong supporter of Carter’s 1976 candidacy, which eventually mobilized a mind-bending coalition of civil-rights activists and their longtime opponents, including George Wallace, James Eastland, and Herman Talmadge.

But if an “evolving” Joe Biden is going to be given the benefit of the doubt on the policies and associations he cultivated for so long, it should be in the light of a clear examination of his progression into the light. If he survives the Democratic nomination contest and takes on Donald Trump, he’ll need all the testing he can get.