Facebook and the Federal Trade Commission have officially settled the matter of whether or not Facebook sucks at protecting user privacy. The answer is, shockingly, “yes.” Today, the commission announced a number of policies that Facebook has agreed to abide by, on top of the $5 billion settlement. It is, I think, safe to say that the FTC got hosed, and the penalties that Facebook is getting hit with are a slap on the wrist, at best.

In addition to the fine, Facebook will have to enact a few privacy mechanisms that mostly just require them to create a paper trail. It also has to audit third-party app developers to ensure that they are compliant with Facebook’s policies regarding data usage. In other words: Facebook has to actively monitor to make sure that Cambridge Analytica doesn’t happen again (the FTC also settled with them recently). The settlement requires the appointment of an independent privacy committee, one whose members can only be removed by a supermajority. This is to ensure that Mark Zuckerberg, who controls enough of the company to unilaterally make decisions without support from any additional members of Facebook’s board of directors, cannot unilaterally make decisions about how the company handles user privacy. That body, plus Zuckerberg and other appointed compliance officers, all need to submit quarterly reports to the FTC.

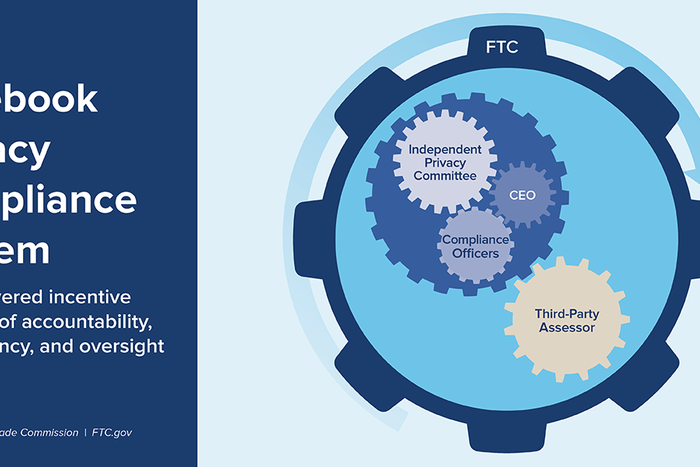

If that’s confusing, allow this convoluted FTC graphic to clear things up for you.

(Side note for anyone who has played too many video-game logic puzzles: If you placed three gears in a triangular formation so that each gear was in contact with the other two, as is shown above, all of the gears would be locked in place and unable to turn. An apt metaphor.)

In addition to this stuff, Facebook is also prohibited from doing a number of other shady things in service of data harvesting. Going forward, it is required to obtain explicit consent from users regarding facial-recognition tech. It cannot ask users for their login credentials to other services (a creepy and invasive request that, yes, Facebook did actually make of certain users). It also cannot use data obtained for security purposes, like phone numbers used in two-part authentication, to fuel its ad targeting (another dishonest and truly messed-up thing that, yes, Facebook actually did).

The FTC voted to approve the settlement 3-2, split along party lines: Republican-approved commissioners voted for, Democratic ones against. The latter group thinks that the settlement is too weak to be effective. Earlier this month, the Washington Post reported that the FTC initially pursued more aggressive penalties, including “fining Facebook not just $5 billion, but tens of billions of dollars, and imposing more direct liability for the company’s chief executive, Mark Zuckerberg. Facebook, however, fiercely resisted the government’s demands, and in the end, the FTC, facing a formidable foe whose $55 billion in revenue last year amounted to almost 200 times the budget afforded to the federal regulators, settled for less.”

In its statement on the matter, which called the settlement a “home run” (lol), the three commissioners who voted to approve argued that this was the best they could get. Rather than fight a protracted legal battle, chairman Joe Simons and commissioners Noah Joshua Phillips and Christine Wilson wrote:

To evaluate whether we would accomplish our goal, we asked: “Is the relief we would obtain through this settlement equal to or better than what we could reasonably obtain through litigation?” If the answer had been “no,” it would have made sense to aggressively move forward in court. The answer, however, was “yes” — because the relief we have secured today is substantially greater than what we realistically might have obtained by litigating, likely for years, in court.

On its face, the logic makes sense. Legal battles are expensive, resource-intensive, slow, and Facebook has very deep pockets. Yet there is evidence that litigation also works at curtailing corporate malevolence, even if not in an official capacity. The antitrust case against Microsoft, which dragged on and eventually petered out without the company getting broken up, still had a cascading effect on how the company operated, which is to say, more carefully.

On top of that, the results that the FTC achieved in the settlement are almost laughable. Mark Zuckerberg, despite having individual and near-complete control over Facebook, is not named as an individual in the settlement. In addition, the company is indemnified from any violations of its privacy agreement with the FTC prior to June of 2019. That effectively wipes the slate clean for Facebook.

But the main reason this settlement fails is because it fails to address the root cause of the Cambridge Analytica scandal in the first place: Facebook’s business model, which relies on aggressive data collection. Aside from the stipulation curtailing the use of data protected for security purposes, Facebook is not really prevented from conducting business as usual — it just needs to have a record of its conduct.

In her dissent, commissioner Rebecca Kelly Slaughter writes that “while the order includes some encouraging injunctive relief, I am skeptical that its terms will have a meaningful disciplining effect on how Facebook treats data and privacy. Specifically, I cannot view the order as adequately deterrent without both meaningful limitations on how Facebook collects, uses, and shares data and public transparency regarding Facebook’s data use and order compliance.”

Rohit Chopra, the other dissenting commissioner, had similar qualms. “The settlement imposes no meaningful changes to the company’s structure or financial incentives, which led to these violations. Nor does it include any restrictions on the company’s mass surveillance or advertising tactics,” he writes. “Instead, the order allows Facebook to decide for itself how much information it can harvest from users and what it can do with that information, as long as it creates a paper trail.”

That the settlement does not do anything to change Facebook’s business model is the fatal flaw in this agreement. The business model, and the incentives it creates, is what led to the privacy issues that eventually led to the Cambridge Analytica scandal and this settlement. That Facebook is not required to change any of its data-collection practices, or the business model that necessitates said collection, all but ensures that it will screw up again.

In a statement posted today, Mark Zuckerberg framed the settlement as a noble mission. “Going forward,” he wrote, “when we ship a new feature that uses data, or modify an existing feature to use data in new ways, we’ll have to document any risks and the steps we’re taking to mitigate them.” That Facebook had to be forced by regulators into this basic accountability practice is embarrassing!

“We expect it will take hundreds of engineers and more than a thousand people across our company to do this important work,” he continued. This is a feint. What Zuckerberg wants to signal is the idea that he is hiring more people and spending more in order to fulfill the terms of the settlement. The sentence does not actually state such.

“And we expect it will take longer to build new products following this process going forward.” This is framed as a downside for users who want new features and want them now, but maybe it’s not the worst idea in the world for a CEO whose past motto, “Move fast and break things,” has had disastrous consequences.