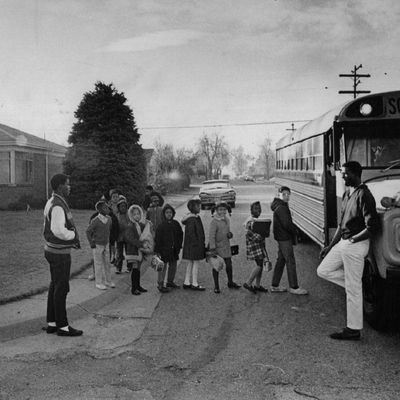

When Kamala Harris upbraided Joe Biden in last week’s Democratic presidential debate for his history of anti-busing activism back in the day, it electrified audiences and made her the clear winner of the evening. The very direct confrontation worked in part because Harris was able to testify to her own experience as a beneficiary of busing as a child, and in part because Biden floundered in answering, lapsing back into states’-rights jargon about the evils of federally mandated busing. More than ever, it made Biden look like a walking political anachronism. He didn’t quite sound like George Wallace with his signature denunciations of “the asinine busing of little school children,” but it was a reminder that Obama’s veep was on the same side of the issue as every racist in America.

But Harris is now in danger of sounding anachronistic herself by calling for a renewed federal commitment to school desegregation along with the use of busing as a tool to achieve it:

Sen. Kamala Harris (D-Calif.) is standing by her support for busing as an effective tool the federal government should use to help desegregate schools.

The 2020 presidential candidate doubled down on her busing comments Sunday in San Francisco after participating in the city’s Pride Parade, according to Bloomberg.

“I support busing,” she told reporters outside city hall. “Listen, the schools of America are as segregated, if not more segregated today than when I was in elementary school. And we need to put every effort, including busing, into play to desegregate the schools.”

Harris’s contention that schools are no more integrated than they were when she was bused in the late 1960s is well-founded, though its accuracy depends on how you measure segregation (by the percentage of isolated school populations, or by the percentage of nonwhite kids who attend majority-white schools). And the research literature continues to show that minority kids benefit from attending racially and economically integrated schools, sometimes quite significantly.

But there’s not much question that the drive to use busing and other unpopular involuntary methods to desegregate schools floundered over the years thanks to a combination of intense political opposition (with Biden’s own posture being a good and hardly unusual example) and the migration of white families out of the affected school districts. When it came to the prospect of cross-district integration of inner-city kids into suburban, majority-white schools (often across major political boundaries) — which was necessarily imposed by unelected judges — the will to persist was steadily eroded by adversity, as P.R. Lockhart recalls:

Busing programs weren’t opposed just in Southern states. In fact, they were often met with even more resistance in the North due to the region’s avoidance of civil rights issues and efforts to claim moral superiority over the South. Busing was heavily criticized in Detroit, for example, where white families boycotted it in 1960 and continued to oppose it in the years after. In Boston, politicians campaigned and won on anti-busing platforms, arguing that black students’ struggles to access a quality education and succeed in schools were not affected by segregation, but were instead the result of pathology. The city also saw a series of violent riots in the 1970s after schools were ordered to desegregate by a court.

As opposition continued, anti-busing proponents argued that their criticism of busing was not opposition to school desegregation as a whole. But it was also true that in districts that had been the most resistant to integration, the absence of busing programs would leave many schools segregated.

In recent years, advocates for equal educational opportunity shifted to other strategies, most notably in the administration of the first African-American president, as this 2010 assessment noted:

[T]he focus from President Obama’s Education Secretary Arne Duncan— former head of Chicago Public Schools — and other urban education leaders is on accountable teachers and schools. There are reasons for that focus, including school integration’s fraught history and sensitive nature, as well as a Supreme Court decision that limits race-based school admissions policies. But for whatever reason, says Richard Kahlenberg, a senior fellow at the Century Foundation and author of several books on education and civil rights, “the whole question of school integration has been off the radar screen in Washington.”

Indeed, in recent years politicians and advocates on the right have focused almost exclusively on “school choice” experiments designed to break the public school “monopoly” on K-12 education entirely, while those on the left have become ever-more-intensely devoted to demanding more funding for traditional public schools and teachers. Until recently, the prevailing trend in K-12 education policy, beloved of business groups and “centrists” in both parties, was standards-and-accountability improvements in “results,” with the George W. Bush–era No Child Left Behind initiative and the subsequent Common Core Curriculum drive probably representing the apogee of that approach. But with liberals and conservatives buying into a grassroots revolt against high-stakes testing, that avenue for improving education equity is looking like a dead end.

So perhaps it is time for something new. And there have been renewed efforts to look at either radical rezoning of school districts to counteract residential segregation (though that has been limited by federal court strictures against race-based education policies) or metro-wide busing that would include charter public schools (notably in Minneapolis).

Part of the problem with the kind of revival of busing initiatives Harris seems to be thinking about is that the term itself is so misleading and invidious, as Dartmouth professor Matthew Delmont, the author of an influential book titled Why Busing Failed, has repeatedly argued:

That word only starts to be used in political debates when people want to oppose school desegregation. That first happened in the late 1950s. It actually starts in New York City, which is the first public protest I found against busing …

School buses had been used starting in the 1920s and ‘30s in the United States. It’s what made the more modern American school system we know now possible. That’s what allowed us to transition from the rural, one-room school houses to larger, more comprehensive schools. That use of school buses was never a controversial issue. It was never a problem among white parents until it got linked to the issue of race and school desegregation. So I would want people to know that busing is a political code word.

The standard differentiation between “forced” and “voluntary” busing, which Biden still uses, represents another heavily loaded set of terms, particularly when it comes to the federal role in encouraging or even demanding desegregation, says Delmont:

[T]he local and the federal roles have always been intertwined with schooling in America, particularly on the school desegregation issue. This sense that communities should only desegregate when they locally decide to do so is farcical. It demonstrates a complete either lack of knowledge or willful misunderstanding of how race and school desegregation played out in the country.

But this is all the more reason Harris has to be careful in reviving the kind of debate that pols like Biden won a generation ago: the very terms are loaded, and to the extent that Americans today even understand contemporary school segregation and possible remedies for it, they still strongly tilt toward neighborhood schools as a policy emphasis, even if that means a significant degree of segregation. A Gallup poll taken in 1999 showed African-Americans split down the middle as to whether maintaining neighborhood schools (48 percent) or busing to achieve racial balance (44 percent) is more important. The same poll, however, showed 90 percent of African-Americans and even 54 percent of whites agreeing that more should be done to integrate schools.

So if Kamala Harris can succeed in reintroducing school desegregation as a relevant topic in national politics, while deemphasizing (without necessarily abandoning) the much-misunderstood and even demonized method of busing to achieve it, she might gain some real gratitude from the black voters she absolutely has to have in the 2020 Democratic nominating contest, and some serious traction against Joe Biden, without damaging her viability elsewhere in the electorate. She might be wise, in fact, to combine this policy commitment with her earlier plan to use federal leverage to raise teacher salaries, and make herself the “public education candidate.” Like so much of Harris’s path to the nomination, it will be tricky, but it’s doable, and would be of great benefit to the country as well as her own political future.