There were times when you were talking with Robert Morgenthau, former colleagues say, that you needed to remind yourself that he was speaking not as a student of modern American history, but as a participant in it, for nearly a century. When Morgenthau spoke about Franklin Delano Roosevelt drinking mint juleps, it was because Morgenthau had mixed the drinks. When Morgenthau talked about the bloody losses at Iwo Jima, it was because he was in the middle of the fighting. When Morgenthau described the shock and agony of President John F. Kennedy’s death, it was because he was with Robert F. Kennedy at Hickory Hill when the terrible phone call arrived.

And all of that came before the signature role of Morgenthau’s career: serving 34 years as Manhattan district attorney. He presided over 3.5 million prosecutions. The city went from 1,645 murders when he took office in 1975 to 471 in 2009, when Morgenthau left. Under Morgenthau, the DA’s office prosecuted Mark David Chapman, Bernie Goetz, Robert Chambers, Tyco’s Dennis Kozlowski, Tupac Shakur, and Brooke Astor’s son. He also oversaw the conviction, and then the exoneration, of the Central Park Five.

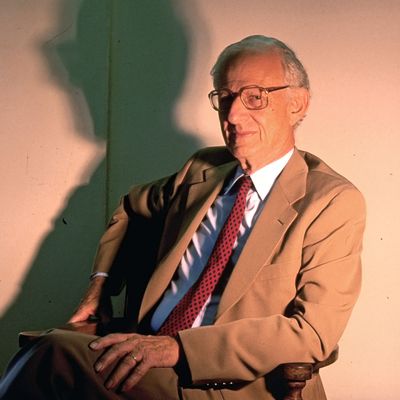

The longevity and the roll call of statistics and events, however, doesn’t capture Morgenthau’s singularity or influence. He was born, in 1919, to an American aristocracy. His paternal grandfather, Henry Morgenthau Sr., had emigrated from Germany in 1866 and amassed a fortune in American real estate, some of which he used to back President Woodrow Wilson. Morgenthau Sr. served as Wilson’s ambassador to the Ottoman empire during World War I and tried unsuccessfully to get the U.S. to stop the Turkish slaughter of Armenians. Henry Jr. had somewhat more success as FDR’s Treasury secretary during World War II, helping persuade the president to belatedly intervene in the Nazi slaughter of Jews.

His youngest son graduated from Deerfield, Amherst, and Yale Law. Robert Morgenthau also enlisted in the Navy, and spent four and a half years at sea during World War II. In 1944 his first ship was sunk by German aircraft and torpedoes off the coast of North Africa; 200 men were killed. A year later Morgenthau was aboard another destroyer that survived Japanese torpedo and dive bomber attacks during the battle of Iwo Jima. All that heroism came with a cost: Morgenthau spent much of the 1950s dealing with undiagnosed PTSD.

Morgenthau later said that while he was treading water in the Mediterranean he made a bargain with God: If he lived, he would go into public service. The chance came at the behest of another rich, young, dynastic Democrat. In 1961 President John F. Kennedy appointed him United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York, but Morgenthau had barely moved into the office before resigning to become the state party’s nominee for governor, a race Morgenthau lost to yet another rich, young scion, Nelson Rockefeller. Kennedy helpfully reinstalled Morgenthau as U.S. Attorney, where he reoriented the office to punch up: instead of going after small-dollar Ponzi schemes, Morgenthau’s SDNY went after CEOs and the accountants and lawyers who enabled frauds, filing criminal charges instead of reaching settlements with fines. “How do you justify prosecuting a 19-year-old who sells drugs on a street corner when you say it’s too complicated to go after the people who move the money?” Morgenthau said. His prosecutors went after the Mafia, and also pursued Roy Cohn and donors to Richard Nixon’s 1968 campaign, which did not endear Morgenthau to the new president. Then he bucked custom by refusing to hand in his resignation after Nixon took office in 1969. Nixon finally pushed Morgenthau out in January 1970. “I hope that my fight for independence will make it easier for my successor to withstand the harsh, narrow partisan views on law enforcement currently in favor at the Department of Justice in Washington,” Morgenthau wrote on his way out the door. His immediate successor as U.S. Attorney did just fine navigating partisan challenges; Preet Bharara, however, found himself repeating Morgenthau’s principled drama 47 years later, after the election of Donald Trump. “Whether he was charging landmark public corruption or organized crime cases, Mr. Morgenthau worked tirelessly to instill public confidence in the independence of the SDNY,” says Geoffrey Berman, whom Trump selected to replace Bharara. “Every day as I enter my office I pass a portrait of Mr. Morgenthau and I am inspired by his lifelong dedication to public service and the law.”

In 1970 Morgenthau made a second short, unsuccessful bid for governor. That turned out to be his final electoral defeat. Morgenthau won the 1974 contest for Manhattan district attorney after the death of another legendary prosecutor, Frank Hogan, and was reelected seven times, running unopposed in general elections from 1985 to 2005. It certainly helped that New York increasingly became a one-party town; Morgenthau’s political skills and his track record helped more. “He created a global reach for the Manhattan DA’s office, when that was not a traditional way of thinking about a local prosecutor,” says Jeremy Travis, whose career in law-enforcement policy has included clerking for Ruth Bader Ginsburg, advising Mayor Ed Koch, and serving as president of John Jay College. Morgenthau’s innovations as DA were rooted in process, not ideology: He established “vertical” prosecution, which allowed a prosecutor to stay with a case from inception to appeal, he opened a branch of the office in Harlem, and he created the citywide office of Special Narcotics Prosecutor. In the early ’80s, when a mid-level prosecutor, Richard Aborn, suggested forming a task force to track illegal guns, Morgenthau eagerly endorsed the idea.

In many ways, though, he took a conventional approach to the job, largely staying out of the policy debates over broken windows policing and stop-and-frisk. “Prosecutors are now asking, ‘What can we do, using the tools of our office, to develop long-term crime reduction strategies?’ That’s a different way of thinking,” Travis says. “Morgenthau was not of that ilk. But nobody else was at the time either. The idea that a DA would have a voice on those issues was not the way the role was conceived then.”

Instead, Morgenthau’s greatest impact came from the way he led his office, and from the caliber of the staff he hired. “From Mr. Morgenthau I took, ‘Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead.’ He didn’t care about the political ramifications,” says Eliot Spitzer, a prosecutor in the Manhattan DA’s office from 1986 to 1992. Rachel Hochhauser spent 16 years in the office working on cases from terrorism to child abuse to financial fraud. “You were working for a person of tremendous integrity,” she says. “The mission of the office was trying to achieve justice and fairness, and you knew those things guided his decisions.” Aborn cites an example. “In the middle of a very serious robbery case, I got some information we might have the wrong guy,” he says. “Morgenthau always told us, ‘Don’t prosecute a case if you don’t believe somebody is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.’ Which isn’t the legal requirement. I wrote him a memo about the robbery case, we discussed it, and then we dropped the case.” Even defense lawyers who butted heads with Morgenthau’s office speak of their respect for his standards. “In terms of serving the people, Morgenthau was a legend, and he was a legend for all the right reasons,” Judd Burstein says. “He was the antithesis of Rudy Giuliani, who pursued things for their publicity value. And not in a million years would Morgenthau have let his office reduce the sex offender status for someone like Jeffrey Epstein.”

There were certainly major controversies and failures on Morgenthau’s watch. The high-profile prosecution of the Bank of Credit and Commerce International, for money laundering and bank fraud, ended with mixed results: The bank was forced to close, but Morgenthau’s prosecution of Democratic fixer Clark Clifford and lawyer Robert Altman ended with the charges against Clifford being dismissed and Altman acquitted. The greatest stain, however, is the 1990 conviction of five young black men for a vicious attack on a female jogger in Central Park. No physical evidence connected them to the crime; their confessions turned out to be bogus. In 2001, when a convicted murderer and rapist admitted he was to blame, and his DNA was matched to a sample from the crime scene, Morgenthau eventually assigned two of his top deputies to reinvestigate, then recommended that the five convictions be thrown out. Morgenthau spoke grudgingly of the episode in 2016, telling John Leland of the Times, “As a matter of policy I don’t look back … I had complete confidence in [chief sex crimes prosecutor] Linda Fairstein. Turned out to be misplaced.”

“That he moved swiftly to vacate the convictions counts for a lot,” says Michael Hardy, a defense lawyer and the general counsel for Reverend Al Sharpton’s National Action Network. “I am not saying that justifies what his office did. But there were fewer stories of wrongful prosecutions under Morgenthau than there were in some of the other counties, Brooklyn in particular. And I remember Mr. Morgenthau looking me right in the eye and asking whether I really thought a federal special counsel would do a better job of prosecuting the cop who shot Ousmane Zongo in Harlem than he would. It’s not one of the cases that you always hear about, and it took two trials, but it was a successful prosecution of a police officer for having killed an unarmed black man in America.”

Morgenthau never really stopped working, even after departing the DA’s office at the end of 2009. For the past decade he left his Upper East Side home and went to Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz. His main efforts were liberalizing immigration laws and crafting a death-penalty appeal for an Alabama man convicted in a 1988 murder. His charitable work included donating a wing of the Jewish Museum of Heritage and passing along the 270-acre Fishkill Farms to one of his sons. His greatest tangible legacy may be training hundreds of lawyers, two of whom have gone on to become governors (Spitzer, Andrew Cuomo) and 80 of whom are judges, including Supreme Court justice Sonia Sotomayor. “He came from the patrician class and he was very serious about public duty, about being of value to the public,” Travis says. “The name of the Morgenthau family meant a lot, and he carried that mantle without being explicit about it.” Robert Morgenthau finally stopped making history, more than any one man would seem capable of making, last night, ten days short of his 100th birthday.