One of the key questions affecting the 2020 Democratic presidential-nomination contest is whether the front-runner candidate most reliant on strong African-American support (Joe Biden) can hang onto that support in the face of opposition from two credible African-American candidates (Kamala Harris and Cory Booker).

At present, Biden really does seem to be in the catbird seat, even after Harris drew blood with her much-discussed criticism of the former veep’s record on school desegregation in the first round of candidate debates. A new national survey from Quinnipiac shows Biden holding 53 percent of the African-American vote, with Bernie Sanders a distant second with 8 percent and Kamala Harris third at 7 percent. Harris, and even more so Booker, at this point mostly just have potential as candidates with a special appeal to this community. What the ceiling is on that potential is not clear, but we have some fascinating historical data bearing on that question from NBC News:

[T]hanks to the assistance of William Mayer, a political scientist at Northeastern University and an expert on presidential campaigns, NBC News has assembled for the first time a publicly available state-by-state record of the black vote for each of the nine competitive national Democratic campaigns since the inception of widespread exit polling.

That would have been in 1976, when southern white moderate governor Jimmy Carter made strong African-American support (particularly in his own region, where he was battling George Wallace) one of the cornerstones of his broad primary coalition. There were many theories about Carter’s (and subsequently other southern white moderate Democratic candidates’) appeal to black voters despite his very recent emergence from a Jim Crow heritage, with cultural affinity (African-Americans were generally more comfortable with Carter’s Evangelical religiosity than were many white voters outside the South) and the backing of the King family ranking high. But four years later, Carter, amid domestic- and foreign-policy setbacks, was challenged for the Democratic nomination by the scion of a family with a powerful connection with black voters, Ted Kennedy. As Steve Kornacki notes in his write-up for NBC, African-Americans split regionally:

In the initial contests in his native South, Carter scored overwhelming statewide victories that were aided by black voters. In Alabama, for instance, he won heavily black areas by 3-to-1, according to estimates at the time — proof, one black Carter supporter declared, that “Edward Kennedy is not John Kennedy at all …”

Kennedy, though, was bypassing the South and banking on a strategy of winning big industrial states. In New York, where he notched his first significant victory, Kennedy bested Carter by 6 percentage points with black voters. In Pennsylvania, where his statewide margin was wider, he routed Carter by nearly 2-to-1 with black voters, according to NBC News’ black voter data analysis.

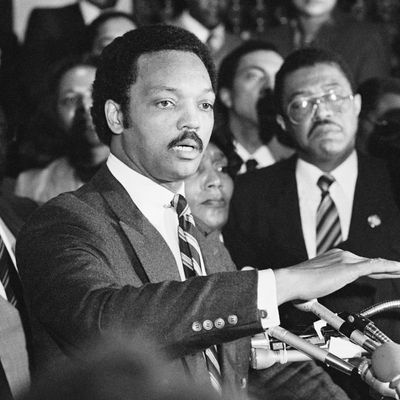

In the end, Kennedy edged Carter among black voters overall, but there was a sense in the African-American community that both candidates were ignoring its priorities. So in 1984 there was fresh interest in someone from that community running for president, and when no one else stepped forward, Jesse Jackson did and everything changed:

Jackson’s campaign was paired with an extensive voter registration drive; the black share of the Democratic primary electorate doubled and even tripled in some states as Jackson’s campaign triggered a wave of interest. His follow-up White House bid in 1988 only reinforced these trends. Taken together, his two campaigns cemented the bond between African Americans and the Democratic Party and significantly increased the size, visibility and clout of black voters within the party’s coalition.

According to exit polls, Jackson won 77 percent of the black vote in the 1984 primaries, and elevated that showing to 92 percent in 1988.

It helped that none of Jackson’s Democratic rivals in either cycle had especially strong ties to the community. And when he chose not to run in 1992, the Carter-era strength of southern white moderates returned as black voters gave Bill Clinton 70 percent of their votes in the primaries.

The 2004 cycle offered a fascinating alternative scenario to the two Jackson candidacies. Not one but two notable African-Americans, former Illinois senator Carol Moseley Braun and media figure–activist the Reverend Al Sharpton, entered the race. Both were arguably as well known and credible as Jackson had been in 1984. But Braun faded fast, exiting the campaign (and endorsing Howard Dean) before the Iowa Caucuses. And while Sharpton stayed in the race until March, he didn’t become anything like the consensus candidate of black voters that Jackson had been. In the pivotal South Carolina primary (which had just been moved to a privileged position early in the year to give African-Americans a stronger influence in the nominating process), Sharpton finished a poor third (17 percent) among black voters, trailing John Edwards (37 percent) and John Kerry (34 percent). In the end Kerry — hardly the model of a Democrat likely to become the favorite of this demographic — won 56 percent of the total African-American vote in the primaries, which may well have reflected a preoccupation with his perceived “electability” in a tough race against an incumbent Republican president (George W. Bush).

In 2008, of course, Barack Obama repeated Jackson’s huge showings (both percentage-wise and in boosting turnout) among black voters, taking 82 percent overall, and trouncing Hillary Clinton (thought to have a strong connection with the community, partially via her husband) among South Carolina’s African-Americans by a 78-to-19 margin. But in 2016, when there were no black candidates, Clinton won 77 percent of the black vote against Bernie Sanders — and 86 percent in South Carolina.

So what does all this suggest about 2020? Are Kamala Harris and Cory Booker (it’s unclear whether both will be viable going into South Carolina) more like Jackson or Obama, or more like Braun and Sharpton? Joe Biden has Clinton-level connections with the African-American community, largely based on his partnership with Obama. Is he more like HRC 2008 or HRC 2016? Perhaps Biden is like Kerry ’04, a candidate with a perceived electability advantage that overcomes the natural edge black candidates have in their own community.

The answer to these questions isn’t just significant in terms of South Carolina: African-Americans represented 24 percent of the total Democratic-primary electorate in 2016, a percentage that could well go up in 2020.

What has probably most changed since 2004 is pretty obvious: Obama showed an African-American can actually win the presidential nomination and then the White House. He was never principally a “protest” or “movement” or “identity” candidate like Jesse Jackson. Kamala Harris and Cory Booker have demonstrated an ability to attract white and Latino voters in (respectively) California and New Jersey. Both are currently polling as well or better among white voters than nonwhite voters. So much may depend on whether either or both of them come out of Iowa, New Hampshire, and Nevada as credible national candidates. If that happens, Biden’s black-voter strength in South Carolina and the rest of the South is very likely to be endangered. And if (as is certainly the best bet right now), it’s Kamala Harris who’s looking strong after Nevada, then a win in the Palmetto State could be a springboard to a Super Tuesday showing (particularly in her home state of California) that puts her into the national lead.

But who knows? If Harris and Booker both fade early on, black voters could also play a crucial role in a contest dominated by white candidates, with Joe Biden counting on his Obama connection and Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren building on ideological appeals and everyone claiming “electability.” For once there is no southern-fried white moderate with a cultural pull; even if Beto O’Rourke turns his campaign around, he’s not going to be as comfortable campaigning in black churches as Carter or the Clintons were. And to a much greater extent than was apparent in the past, it’s entirely possible African-American voters could split on generational lines, with younger black voters gravitating to the more ideologically progressive candidates regardless of race.

This is one of many variables affecting the battle to determine an opponent for Donald Trump in this highest of high-stakes elections. But it’s one that in the end could matter most if the cookie crumbles a certain way and black voters are given the chance to give or deny a candidate a breakthrough.