The Washington Post’s Dan Balz is a justly esteemed political reporter and analyst, with a particularly strong expertise in presidential elections. The 2008 and 2012 “campaign books” he co-wrote were both sound guides to very complicated events.

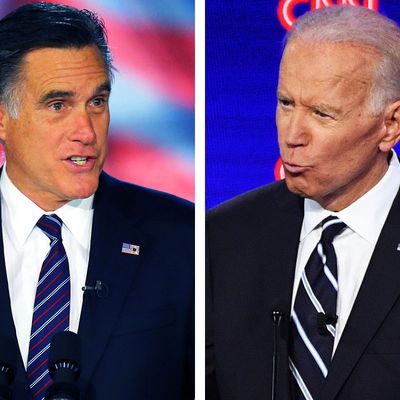

So when Balz introduces an analytical argument into 2020 presidential campaign coverage there’s a good chance it will be repeated by others and help shape the conventional wisdom. That’s why a column from him suggesting strong similarities between Joe Biden and Mitt Romney as presidential candidates is worth examining.

Balz isn’t the first to make this argument, of course. His young Post colleague David Byler did so in June in a column focused strictly on Biden’s chances of winning the nomination as a solid but not overwhelming front-runner — like Mitt Romney.

Balz’s basic hypothesis is that Democrats today like Republicans in 2012 are in danger of “settling” for a nominee with clear weaknesses who is out of touch with his party’s zeitgeist. Like Mitt Romney, he says, Joe Biden lacks “respect” from party activists, but could prevail over divided opposition through a series of tactical wins with negative consequences for the general election:

The Romney experience shows how a candidate who leads the polls but gets only nominal respect can prevail in a nomination contest. But that long campaign also left him branded and weakened for the general election against Obama. Biden’s task will be to show that, whatever missteps and misstatements he might make, he is better than any of the others seeking the nomination — and do that in a way that does not weaken him for a general-election campaign against a president who plays by nobody’s rules but his own.

I certainly share the concerns many observers have about Joe Biden’s strength in a contest against Donald J. Trump. But I don’t think his problems are parallel to Romney’s.

Yes, Romney’s background as a moderate governor of Massachusetts made many conservatives mistrust him. But part of that mistrust flowed from Mitt’s reputation as an unprincipled flip-flopper. He tried to run in 2008 as the “movement conservative” candidate and constantly tried to calibrate his ideological image throughout the 2012 cycle. And so conservative attitudes toward Romney became as transactional as they thought he was: he didn’t satisfy them during the general election campaign until he chose Paul Ryan as his running-mate, thus confirming their future control of the GOP.

If anything, the problem with Joe Biden’s long record has been the opposite of herky-jerky opportunism: he’s stuck to his stated principles far too long, and expressed too much pride in things he said and did that are today problematic. Progressives may think he’s wrong about important subjects, but they don’t think he’d do and say anything to win elections. That’s a difference between Romney and Biden that clearly does matter to general election swing voters.

Romney’s other problem in 2012 is that he did not inspire a lot of personal affection from his partisan backers, with the exception of LDS folk for whom he was an important symbol of mainstream acceptance. By contrast, it’s a byword among Democrats that everybody loves Joe (or as Balz concedes, he has “more good will across the party than did Romney.”) After months and months of pounding from progressive activists and journalists regarding the more atavistic elements of his record in the Senate, Biden’s favorability ratio among Democrats (according to Morning Consult) is currently 75/18. The same pollster shows Biden as the top second-choice candidate for Bernie Sanders supporters. As Balz himself notes, Biden’s levels of support are so far stronger than Romney’s were in the early stages of the 2012 cycle — even though the Democrat faces a larger, and arguably much stronger, field of opponents. So Biden has both favorability and electability in his favor.

On the other hand, Biden cannot count on Romney’s occasionally very good luck, as when his strongest rival, Rick Perry, imploded during two debates (though Romney gave him a good push with attacks on his vulnerable position on immigration policy) and never recovered. It’s also not entirely clear that Team Biden is as tactically ruthless as Romney regularly was (though Biden’s newly aggressive behavior after his first-debate setback indicates he might be).

Assuming he can continue to serve as a plausible unity candidate for Democrats despite progressive activist and media hostility, the big question concerning Biden’s general election viability is whether it will wind up being a foil to his opponent’s most powerful attack lines. In the end, this is probably what did in Mitt Romney: his personification of the Obama campaign’s charge that Republicans were “out of touch” and incapable of escaping the perspective of the wealthy “job-creators” they lionized. That’s why the famous “47 percent video” — in which the candidate wrote off nearly half the electorate as hopelessly dependent on government — probably destroyed Romney’s last chance at an upset.

Biden would not appear to be especially vulnerable to the Republicans’ preferred 2020 attack on Democrats as wild-eyed baby-killing socialist radicals who hate America and want to take away everybody’s health insurance. Indeed, part of what makes him seem so “electable” in a cycle where that quality is so important to his party is that he simultaneously shows appeal both to African-Americans and to the white working-class voters most prone to racial resentment. That’s quite the mind-boggling coalition.

Yet Biden, the 44-year veteran of the United States Senate, (including eight years presiding over that institution as veep) might be immensely vulnerable to attacks on him as embodying the D.C. “Swamp” (one thing that Romney, the consummate business consultant with just four years in elected office, all of it away from Washington, didn’t have to worry about). What’s unclear is whether an incumbent president awash in corruption is capable of credibly sustaining such an attack. And in the end that is the irreducible difference separating Romney and Biden that no list of similarities can efface: the character of the presidents they have challenged. That Mitt Romney can’t bring himself to say much nice about his immediate successor as Republican presidential nominee tells you a lot about Biden’s stronger general-election potential — if he just doesn’t blow it.