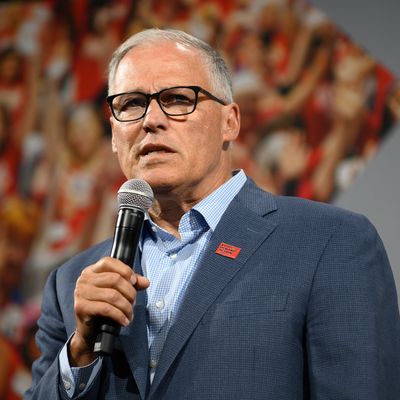

The Democratic field no longer has a climate candidate. Washington governor Jay Inslee, who made global warming the centerpiece of his long-shot campaign for the presidency, announced Wednesday evening that he was dropping out of the race, facing the prospect that CNN might stage a forum on climate change for Democratic candidates for which Inslee himself would fail to qualify.

The governor didn’t need to run on climate change alone — he’s a well-liked governor in a thriving state, with an enviable liberal record on job creation, economic growth, minimum-wage increases, and family-leave policy that seemed, in theory at least, to offer a powerful case study in how Democrats could move forward on climate change while accomplishing everything else they might want. But while his six-part climate policy may become the road map for a future Democratic administration, it isn’t going to be his, and, at the moment when Democratic voters tell pollsters they are unprecedentedly concerned about the environment (naming climate change as a top-tier issue in many state polls), they aren’t going to be nominating the one candidate who really prioritized it. Earlier Wednesday, we talked to him about what happened.

First, I just wanted to congratulate you on the incredibly principled and important campaign you’ve run. It’s so important that I’m personally pretty distressed and disheartened that it’s ending. How are you feeling?

Well, I’m not going to end up in the White House, which was the goal. But there have been several things that have been accomplished. Number one, we made a governing document on clean energy and the environment for the United States. Now that document is going to be open sourced, and I’m going to call on the other candidates to be more committed to the issue. I think you saw on the campaign trail that other candidates had to respond to our clarity and vision, and I think it was an accomplishment to get the other candidates to raise their ambitions. Going forward, I’ll be just as vocal about that.

I think we have set the stage for a genuine debate about climate change, in one form or another. We have the two forums coming up, and I’m hoping that there will be a proper debate, too — that will be voted on soon, and it was not going to take place otherwise. And I think it was significant achievement to get this on the country’s radar screen — that was an accomplishment, too.

But the most satisfying thing was that we worked with the grassroots, which has been so inspirational. We did get to 130,000 strong, in terms of donors, which is something only half the field achieved, I believe. And working with the young people all across the country — with Sunrise, the climate strikers, Alexandria Villaseñor. And to have people recognize those movements, and respond to them. One of the things that’s been inspiring to me, traveling the country during the campaign, was seeing how many people are part of this energy revolution. I thought I knew something about it, having worked on this for 25 years, but it was still inspiring.

We’ve talked about this before, but it’s remarkable how you can always see the state of climate change in two ways — that things are moving very quickly in the right direction, and that we’re very quickly running out of time

It’s a race of two rapidly accelerating streams of reality. But the passion is undiminished, the need is increasing, and our confidence is increased. And this energy revolution continues to take place.

How do you see the role for climate change evolving as the primary campaign continues? To this point, even with you in the race and with polling showing it as a top-shelf issue for voters, it’s been a relatively marginal part of the campaign — just a few debate questions, and those posed with such a focus on cost rather than urgency or opportunity they were practically right-wing talking points. Do you think it will be a big part of the rest of the campaign, or remain a second- or third-order issue?

I think we set the stage for it to become a primary issue — by demanding and to some degree accomplishing that it will be part of the debates.

Are you surprised your campaign didn’t get more traction?

Some things are mysteries in life, and obviously we didn’t achieve the goals we set out to achieve. But we always we knew we’d be underdogs, coming with no name ID, no money in the bank, and coming from the Northwest corner of the country, far from the media center. To some degree it’s an academically interesting question but irrelevant — there’s only one medal in this race, and no silver and bronze. But I do think we succeeded in raising the profile of the issue, and I do believe there were significant accomplishments on climate issues that would not have happened, probably, if I wasn’t in the race.

It’s interesting to think about your experience as governor — it used to be that being a popular governor was a positive qualification for the presidency, but these days national name recognition seems to be much more important, and favors senators and even congresspeople, even though their jobs are really very different from being president. Not to mention businesspeople.

As you know, having executive experience is a really valuable thing, but obviously the three governors in the race haven’t set the world on fire. But there are structural reasons for that, too. One is that we’ve gone to a national press corps, where the local and regional press is diminished, so the only place people get their political news is from the national media, which is in New York and D.C.

Second, the way this campaign was set up favored those who had name ID early — the debate rules, I mean, which were set up to eliminate the prospects of those who did not. So would Bill Clinton and Jimmy Carter have thrived under these rules? Maybe not, because they wouldn’t have been able to grow during the campaign. I’m not complaining about the rules, but they were the rules. Also, going forward, governors can’t roll over campaign donations into other elections, like senators and congresspeople can — and that’s an additional disadvantage.

But we knew all that when we started. And we wanted to have the opportunity to present a vision statement. Which we did. And, by the way, it’s not a small thing to have 130,000 donors. That’s a lot of people, and they’re not just answering a polling question, they’re voting with their money, they’re sending checks.

It’s impressive, especially given where climate seemed to be in the part as recently as the last presidential cycle. But I want to ask about your policy documents on climate. I’ve told this to you before, but I think of them not just as best in class but a category above — even compared to proposals from other candidates I really admire. The plan came in six parts — you just released one of them today, actually. What will be the fate of those plans, do you think?

Well, it’s open source, now. We’re not claiming copyright, so we’re hoping other candidates use it as a template going forward. There are hundreds of policy ideas for people to run with, so I hope they do.

For us, it was very important to us that those plans form a governing document rather than a campaign document. There’s a reason for that — we wanted to provide meat on the bone and not just a bumper sticker.

I wonder if you can talk in particular about the American leadership one. Given the state of geopolitics, how can the U.S. use what power it has to change the shape of global policy on climate issues?

Well, my plan is the absolute antithesis of the Trump administration. His response to climate change is to try to buy Greenland — to try and make it a golf course. Ours is to embed climate change in all of our foreign policy and foreign relations. That’s the scale of things that has to be done. Climate change has to be part of our trade negotiations. It has to be part of our national security relationships. It certainly has to be part of what you could call a Paris agreement 2.0, where the world has to raise and accelerate its timeline for success on emissions reduction. It has to be a part of all of our foreign policy goals. The Trump administration approach is the opposite — to try and make a buck off human suffering.

And what will happen on climate, do you think, if Trump wins reelection?

In the event that disaster took place, I know the island I live on would want to sell itself to Denmark. I wouldn’t want to — I want to remain a part of the union. But we just don’t want to contemplate that, because the next administration is the last chance to meet these deadlines. Science is uncompromising, and the laws of thermodynamics won’t care whether it happens or not. So I just don’t want to contemplate the possibility. How’s that for an answer?

Yeah, it scares me too.

But I think there’s a good reason it won’t happen, by the way. The country’s had a bellyful of that chaos and daily trauma. They’ve had enough of Cornyn saying climate change isn’t happening because it’s supposed to be hot in July.

It was the hottest month ever on record. And the other day Dinesh D’Souza tweeted a video of snow in Australia as though it disproved climate change, apparently not realizing that it was winter down there. Do you think Americans are waking up on climate, generally speaking? Do you think it can be a winning issue for Democrats as soon as next November?

Yes, and it’s wrapped up in a larger recognition of how terrible Donald Trump is on all things environmental. One of the things Trump showed us recently is how afraid he is of environmental issues. He went out and tried to say he was an environmentalist.

He was bragging about clean American air and clean American water.

Why would he do something so embarrassing? It’s because his lowest rating is on the environment. And he knows that and tried to do something about it. And as disasters continue to mount and the urgency of the crisis intensifies, people see that. It’s already happening. Half of Republicans see this as a problem. It’s just the politicians that can’t break our addiction to fossil fuels.