During one of her biggest campaign rallies to date, Senator Elizabeth Warren taught her supporters a history lesson. At the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, not far from where they stood in Washington Square Park, 146 women and girls once perished in a fire. It was not an act of God, Warren explained, but a preventable tragedy. Oily factory floors fed the flames and the women had no way to escape. The factory owners had locked the door to prevent the workers from stealing cloth.

Some climbed out the windows, looking for a faster exit. “A woman jumped, and then another, and then another. They hit the ground with a sickening thud,” Warren said. “Bodies piled up. Blood ran into the gutter. Dozens more were trapped inside.” It is a pivotal moment in American labor history, if not the usual stuff of a campaign stump speech. For Warren, though, it was a springboard, a way to introduce the anti-corruption platform she’d launched that morning. Factory owners did not reform practices of their own free will; in Warren’s telling, they initially relied on corruption to grind the gears of progress to a halt. Conditions only changed because advocates like Frances Perkins forced them to do so. It’s an intelligent framing, and one that is by now common to Warren; the marriage of policy to a memorable story is one that can galvanize voters. The Triangle story in particular serves a dual purpose. Warren, standing atop a platform made from Frances Perkins’s old barn, is making a bid for progressive history. She’s aligning herself with Perkins, who eventually became FDR’s secretary of Labor, and thus, the first woman in the presidential line of succession.

And whether she means to or not, Warren is distinguishing herself from the party’s last major female nominee in the process. Warren and Hillary Clinton do share some superficial similarities. Beyond the obvious — they are both white women running for the Democratic nomination — they both possess a certain technocratic sensibility. Like Clinton, Warren emphasizes her vast professional experience and her policy proposals. Her regular announcement, “I’ve got a plan for that,” has become a major applause line on the campaign trail. It’s reminiscent of Clinton, who rolled out white paper after white paper in 2016 and who seemed, as Chuck Todd once infamously declared, “overprepared.” But Warren’s Washington Square speech also highlighted the differences between the two candidates. Clinton leaned into pragmatism and alienated the left, but Warren’s other rallying cry, for “big structural change,” isn’t very Clintonesque.

Compare the stump speeches they were giving during the primaries, and the differences between the candidates become even more difficult to ignore. Clinton spoke, often, of an America that had never really existed. She praised its innate virtue, its problem-solving abilities, its grit and its vigor. “The faith that we can make things better, that we can give our kids a better future than we had, is at the heart of who we are as a nation,” she said after winning the Pennsylvania primary. “And it’s one of the many reasons that being American has always been such a blessing.” The problem, as many of her left-wing critics pointed out at the time, is that if being American has ever really a blessing, it has only been a blessing for some. America’s past is littered with factory fires and bigger, darker tragedies. Its present is often just as ugly. Clinton’s rhetoric, in tandem with policies that clung to an incremental vision of progress, only made her sound aloof. Her reliance on wealthy donors and her friendly relationships with Wall Street interests might have been typical for Democrats, but weighed her down even further.

Clinton’s American exceptionalism isn’t unusual for a politician. Good luck finding one who will get up onstage and tell the assembled that their country is hideous, even though it’s true. In Clinton’s case, her status as the outgoing president’s former secretary of State restricted her even further; a truthful articulation of America’s outrages would have implicated her boss, and by extension, herself. That conundrum also lent credence to left-wing criticisms of her candidacy. The party preordained her nomination, despite her personal and professional baggage and the material needs of their own base. Clinton’s vision of America as an essentially good and fair place didn’t turn out the very voters she needed to win, and no wonder. Who wants to hear that America’s already great when they’re trying to support themselves on the minimum wage? Clinton didn’t push a frustrated public into the arms of Donald Trump as much as she failed to rally them to her side.

Warren’s made her own mistakes. She once looked like a long shot, her candidacy doomed early by a series of hamfisted gestures.There’s the DNA test, which she took to prove that she had Cherokee ancestry, as she’d claimed for years. But she isn’t an enrolled member of a tribe, and Native activists criticized her for undermining tribal sovereignty. Then there’s her Fact Squad website, which is still live, still assuring the curious that Warren has not taken the antipsychotic drug Risperdal. Like the DNA test, the website is intended to debunk right-wing conspiracy theories. Both backfired in their own special way, and both made her look nonserious, almost clumsy, right as she introduced herself to the national electorate.

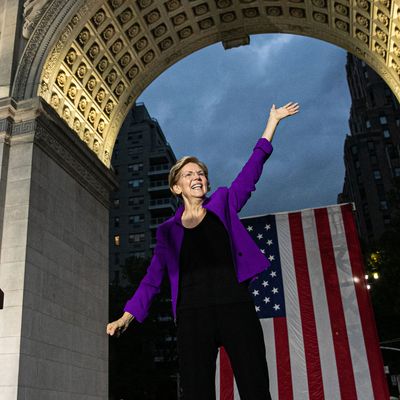

But the Elizabeth Warren who took the stage in Washington Square Park didn’t sound clumsy. She didn’t sound very much like Hillary Clinton, either. Where Clinton sounded passive, Warren sounded urgent, even outraged. “This small slice at the top hasn’t just scooped up a huge chunk of the wealth that all of us have worked so hard to produce. They have gobbled up opportunity itself,” she told the crowd. And where Clinton pledged to defend norms from the likes of Donald Trump, Warren insists that the norms we have are inadequate. Where Clinton was the ultimate insider, Warren, according to one recent Politico report, alienated veterans of the Obama administration by criticizing them for their handling of the recession. She promises change, or at least norms we can believe in. And for a lot of people, that’s enough. The Working Families Party endorsed Warren the morning of the rally, and she’s consistently moved up in the polls. She often ranks directly behind Joe Biden, the front-runner, and she’s at least pulled even with her nearest ideological competitor, Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont. That’s real momentum, but will it last?

The Sanders base is not as ideologically straightforward as some of its centrist critics have suggested; according to Morning Consult, 29 percent describe former Vice-President Joe Biden as their second-choice nominee, and 28 percent listed Warren. Biden supporters narrowly prefer Sanders to Warren. Warren supporters, meanwhile, prefer Sanders to Biden — again, by a slim margin. Warren can’t inspire the nostalgia that powers the Biden campaign; her chances, instead, may be defined by her ability to persuade Sanders voters. And that could prove difficult. Sanders, in 2016, expanded the boundaries of the possible. It’s largely because of him that Medicare for All moved from fringe policy to recurring debate topic. He still leads with younger voters, and he’s released a series of detailed and generous proposals to shore up labor rights, expand affordable housing, and implement a Green New Deal. To pundits, this is all evidence that Sanders occupies a far-left lane. Voters, however, seem to see things differently; to them, Sanders-style populism may stand on its own, a force not easily reducible to a left versus right binary.

Warren is well on her way to convincing liberals that she’s the Goldilocks candidate, neither Clinton nor Sanders but something in between: a true social democrat. It’s why she’s now a major contender for the nomination. But there are long months ahead, and victory may take more than avoiding Hillary Clinton’s mistakes.