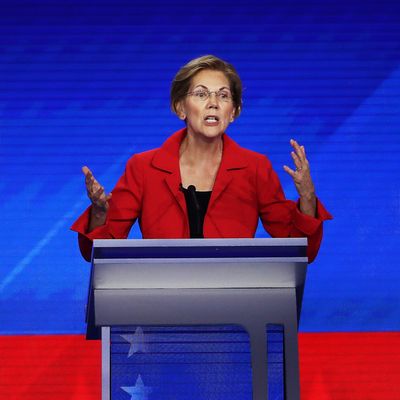

In all three of the Democratic presidential candidate debates, and in the broader discussion of the contest elsewhere, supporters of single-payer Medicare for All have been pushed by moderators, rivals, and journalists from across the political spectrum to “admit” their proposals would boost middle-class taxes and upset Americans loath to give up their current, largely employer-sponsored, private health insurance. This insistent demand has mostly been aimed at Elizabeth Warren, presumably because she has generally opposed middle-class tax increases. Warren has regularly responded that the elimination of out-of-pocket health-care expenditures would mean that total “costs” for middle-class families would go down, and that nobody really likes private health insurance if something better (i.e., Medicare for All) is on offer.

Back and forth goes this exchange, with those asking the question already knowing the answer, and Warren being evasive because she knows that headlines saying she favors a “middle-class tax increase” would not be good for her campaign. Now there is a growing chorus of political observers openly hoping Warren will hedge her bets on Medicare for All, supporting some modification or backup plan the way, say, Kamala Harris has done (however clumsily). Today Jennifer Rubin all but stamps her foot in frustration at Warren’s stubbornness:

Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) is running arguably the best campaign of any Democratic presidential contender. She’s got a message. She’s got enthusiastic fans. She’s got organization. She’s not prone to making errors …

However, on health care, no matter how many times she is asked whether taxes will go up, she insists “costs” will go down for the middle class. It’s becoming rather obvious she doesn’t want to tell us who is going to pay what for her big, structural change.

My colleague Jonathan Chait, in a piece on Warren’s electability, encourages her to change her position before she damages her ability to beat Trump:

One can imagine other steps Warren can take to shore up her vulnerabilities in the coming months. She could produce her own health-care plan, one that leaves the option of employer-sponsored insurance in place. She could promise not to raise middle-class taxes, and that such a promise would take priority over enacting the full panoply of her domestic agenda.

That may be good advice, but at this late date, Warren probably isn’t going to take it. For whatever reason, she’s decided health care is one area where she needs no “plan” because Sanders has already proposed what needs to be done. But I would argue there is something she could begin to say that does not contradict her (or Bernie’s) current position but does show some political realism and a sensitivity to legitimate public fears:

Look, I understand people are afraid to give up the health insurance they have for something unknown and unprecedented, which is one reason why we’ve chosen the very familiar Medicare program as our model. Still, people are not easily going to believe a new program can be better than everyone’s private insurance and that it will wipe out all those out-of-pocket costs, including premiums, copays, deductibles, and non-covered procedures. So here’s my promise: If a Medicare for All bill comes to my desk that does not wipe out these costs so as to far outweigh any taxes necessary to pay for it, and does not give Americans better coverage than they have today — I will veto it. I do not expect anyone to buy a pig in a poke, because I wouldn’t, either.

The “pig in a poke” line is negotiable, though it might just ring true coming from a candidate like Warren, who is successfully beginning to sound like a working-class overachiever from Oklahoma rather than a professor at Harvard. The important thing is that a “populist” like Warren needs to understand that her potential voters fear clumsy big government and deceitful politicians as much as avaricious drug and insurance companies. She should be offering a bottom-line proposition, not a “program.” She can do that without changing her position, abandoning Sanders, or hedging on her own conviction that getting the profits out of health insurance can dramatically lower costs while expanding coverage. All she has to do is to empathize with those who fear change, and that will go a long way toward building on the relatability she has shown in defending working people against corporate power.