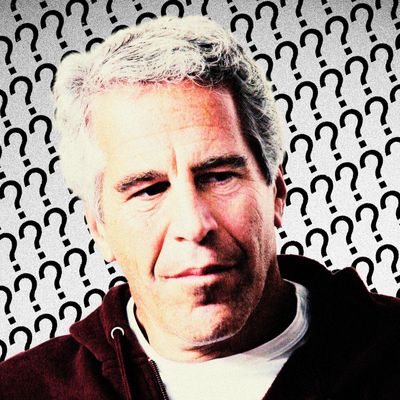

The hydra of the Epstein scandal — in which each sliver of reporting resolves one question only to raise two or three more unnerving inquiries — keeps growing heads. The latest instance in this profoundly frustrating phenomenon involves a report from Ronan Farrow in the New Yorker detailing the MIT Media Lab’s acceptance of Epstein-tainted money well after his 2008 conviction for soliciting an underage girl for prostitution.

Despite his own connections with elite financiers, Media Lab director Joi Ito approved not only two donations from Epstein worth $1.725 million, but allowed the convicted pedophile to “direct” funds from other ultrarich benefactors to the school. Those gifts are said to include $2 million from Bill Gates in 2014 and $5.5 million from Leon Black, the founder of the massive private-equity firm Apollo Global Management.

Epstein was “disqualified” from the donor base of the MIT Media Lab — something of an East Coast answer to the cash-rich tech optimism of Stanford — so Ito and the lab’s director of development and strategy, Peter Cohen, reportedly had to hide his fundraising role, writing in emails that “Jeffrey money needs to be anonymous.” When meeting with the financier on-campus, they wrote only “ J.E.” on their public schedule.

That Ito attempted to obscure Epstein’s involvement in the donation process isn’t all that surprising: To rub shoulders with Epstein then pretend it never happened is a common game in elite institutions. But why would an institution as tech-famous as the MIT Media Lab require a pariah financier to contact two billionaires who are highly active in public life and philanthropy?

Bill Gates and MIT certainly didn’t need an introduction from Epstein: In 1999, the Microsoft co-founder donated $20 million to the university for a computer lab named after himself designed by Pritzker-winning architect Frank Gehry. And it’s not like Gates would have required any rigorous arm-pulling to hand a paltry $2 million over to the school: With a net worth of around $104 billion, the second-wealthiest man in the U.S. is so rich that his $2 million MIT donation is equivalent to an average American spending just $2. Though the New Yorker reported that Ito wrote in an internal email, “This is a $2M gift from Bill Gates directed by Jeffrey Epstein,” Gates has released several statements in recent days denying that his donations were made through Epstein. A spokesperson told the New Yorker that “any claim that Epstein directed any programmatic or personal grantmaking for Bill Gates is completely false.” On Monday, a Gates representative told the AP that his 2014 donation went directly to the university and wasn’t dedicated to the program Epstein was fundraising for, adding that his office wasn’t aware of any discussions between Epstein and the lab.

Considering Leon Black’s reputation in philanthropic circles, one also imagines that a school with a donation-industrial complex wouldn’t have to rely on one of the world’s most toxic middlemen to get a hold of him. Black, the chairman of MoMA worth almost $8 billion, has donated extensively to arts organizations and to melanoma research, following his wife’s diagnosis in 2007.

It certainly seems plausible that Joi Ito or professional fundraiser Peter Cohen would be able to contact these men. Ito, an early investor in Twitter, Kickstarter, and Flickr, was recently described by the New York Times as a “master networker — one who visited the Obama White House to discuss artificial intelligence and became friends with the respected Harvard lawyer Lawrence Lessig after criticizing Mr. Lessig’s book when he gave a talk in Japan.” And yet, the MIT Media Lab reportedly pursued Black’s and Gates’s donations through Epstein, even though some of Ito’s staff referred to the financier as “he who must not be named.” Management tip: If your personnel likens a business partner to Voldemort, it’s a bad sign.

Like so many questions in the Epstein scandal, this leaves those of us outside the rarefied circle wondering why elite institutions would participate in the laundering of a serial child abuser’s money and reputation. Though MIT is part of a larger academic and philanthropic reckoning with accepting the money of bad men, Ito is taking the fall: Within 24 hours, he resigned from his position at MIT, and soon left his visiting professorship at Harvard, as well as his board seats at the MacArthur Foundation, the New York Times Company, and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Cohen has been placed on paid administrative leave at Brown University, where he is currently employed as a director of development for computer science and data initiatives. He said in a statement released Tuesday that despite his “personal discomfort regarding Mr. Epstein,” he does not feel he was in a position to change MIT’s procedures for handling Epstein donations, which were established before his hiring. MIT’s general counsel has contacted an outside law firm to oversee an independent investigation into the matter.

This sub-scandal in the larger Epstein web shows, again, that most of the upper-upper echelon seems to fit nicely within a little black book. Prior to their MIT gifts, both donors knew Epstein. In 2013, according to a report from CNBC, Gates met with the financier in New York after being “inundated with outreach” from Epstein’s camp, who wanted to discuss “growing philanthropy.” After the meeting, Gates — then chairman of Microsoft — hitched a ride to Florida on Epstein’s private plane. In a Wall Street Journal interview published Tuesday, which was conducted before the MIT donation story broke, Gates downplayed his relationship with the financier:

I met him. I didn’t have any business relationship or friendship with him. I didn’t go to New Mexico or Florida or Palm Beach or any of that. There were people around him who were saying, hey, if you want to raise money for global health and get more philanthropy, he knows a lot of rich people. Every meeting where I was with him were meetings with men. I was never at any parties or anything like that. He never donated any money to anything that I know about.

Black, too, had post-conviction contacts with Epstein, though his were more extensive. Black’s family foundation listed Epstein as its director until 2012, though it now claims he was ditched in 2007 due to a “recording error.” But sightings of the two together at a movie screening just months after Epstein’s probation lapsed in 2010, and of Epstein at Black’s home in the Hamptons in 2015 show a more recent, and more personal, connection.

Perhaps the only excuse MIT has for accommodating Epstein in their fundraising practice is his claim that he would ensure that funds donated by Gates and Black would be matched by the John Templeton Foundation, a nonprofit that supports scientific research dealing with matters of faith. (A spokesperson told the New Yorker there was no such arrangement on the organization’s books.) But even that glimmer of justification for bringing Epstein in is dampened by the on-the-ground details: When development director Peter Cohen told former Media Lab development associate and alumni coordinator Signe Swenson of Epstein’s involvement, he seemingly did so “to test whether I would be confidential and sort of feel out whether I would be okay with the situation,” she said.

A handful of people involved in this episode did raise the moral concerns about Epstein that have proven to be in deficit among the global elite. Swenson said that in the summer of 2015, “it hit” her that “this pedophile is going to be in our office.” When Epstein showed up, he brought along two female “assistants,” whom Swenson described as Eastern European–looking models. “All of us women made it a point to be super nice to them,” she told the New Yorker. “We literally had a conversation about how, on the off chance that they’re not there by choice, we could maybe help them.” Swenson resigned the next year, though she says she still “feels guilty.”