On September 23, the United Nations will open its Climate Action Summit here in New York, three days after the Global Climate Strike, led by Greta Thunberg, will sweep through thousands of cities across the globe. To mark the occasion, Intelligencer will be publishing “State of the World,” a series of in-depth interviews with climate leaders from Bill Gates and Naomi Klein to Rhiana Gunn-Wright and William Nordhaus, interrogating just how they see the precarious climate future of the planet — and just how hopeful they think we should all be about avoiding catastrophic warming. (Unfortunately, very few are hopeful themselves.)

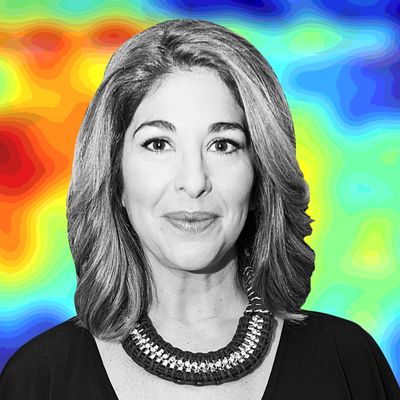

This week, the iconic leftist intellectual Naomi Klein released her latest collection of essays, On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New Deal. Klein was not always so focused on climate change, but three of her past four books have addressed it, beginning with 2014’s This Changes Everything, about as succinct a description of the totality of the threat and challenge posed by climate change as you can imagine. I spoke with Klein in August about the suddenly imminent right-wing responses to the crisis of warming, the new political momentum on climate and the inadequacy of left-wing organizing infrastructure to channel it, and whether we have to give up on consumption and growth to give ourselves a meaningful chance of averting disaster.

In the introduction to your new book, you talk a bit about the prospect of ecofascism, which has been discussed a lot in recent weeks. But you also write about “climate barbarism,” something short of true fascism that is nevertheless defined by real brutality in response to climate change. Is that here already?

I think climate is bringing out barbarism. I don’t think it’s creating it, and I don’t think it’s the only factor. But I think there’s a subconscious understanding, even among climate-change deniers, that we are entering an era of scarcity.

How does that play out?

Barbaric ideas have always served a purpose, and they never went away, because we’ve never truly confronted them or had any true historical record. And so they ebb and flow depending on how much they are needed to justify barbarism. They were needed in the ’80s, to a lesser degree, to justify a tax on the social safety net — you had to have a way of vilifying black people and welfare communities in order to justify the savage tax. White supremacy was born of a need to justify slavery, not the other way around. So I find myself more and more impatient with these ideas that the climate solutions we should be proposing are the ones that pacify the right and that reassure a world based on a hierarchy of human lives and domination.

What solutions do you mean?

We know people who have a hierarchical worldview are more prone than any other group to deny climate change. All the social science shows this. And then you have all of these so-called climate-policy experts who say therefore we should be talking about a revenue-neutral carbon tax, nuclear power, and geoengineering because that is not threatening to the people who hold that worldview.

The problem is that people who hold that worldview are also okay with kids dying in the desert and drowning in the Mediterranean, and unless we actually confront just how toxic that worldview is, all of this is going to get worse. That’s where I think we’re at, and I think at the moment we are seeing an intensification of the climate crisis, an acceleration, everything happening faster than most of the models predicted, as you well know. And we’re seeing a surge in unmasked white supremacy, and we’re also seeing a powerful counterresponse in the form of the Sunrise Movement and the new climate strikers, Extinction Rebellion.

When I look at the very present tense, that’s the most new thing to me. When I think about all the other forces that are conspiring against action, they’re villainous, but they’re also familiar. They’ve been villainous for a while, but a year or two ago, I’m not sure I would’ve thought the mass public protests we’re seeing on climate were even possible

But I also wouldn’t have necessarily predicted Jair Bolsonaro. I think the extent to which, in country after country, we’re seeing the worst people in the world being elevated to the most powerful positions is pretty startling. Boris Johnson — these are people that are ready to just burn it down, and I think [we need to] understand what is behind that, and I don’t think we really have understood what the commonalities are between the Trumps and the Bolsanaros and the Dutertes and the Modis. Another factor is just what’s happening to our mental focus and our ability to have institutions, progressive institutions, that are capable of meeting this moment. That’s what preoccupies me the most, to tell you the truth.

How do you see that landscape?

I’m really concerned about the social-movement infrastructure on the left side of the spectrum. I think it is actually in worse shape than it has been in a long time. You’ve got some powerful presidential campaigns, but that’s not the same as actually having powerful institutions. We’re spending way too much time trading on fear as opposed to organizing strategically and organizing a majority of people who feel that way into a force that can actually defeat the really truly evil forces we’re up against and come up with a plan for how to get out of this.

What about the Green New Deal?

I think the Green New Deal is an incredibly hopeful development, but what we don’t have is the institutional capacity to flush out what that means. The original idea was for there to be a subcommittee that would be a resource, that we would be spending this year consulting, bringing together the movement and scientists and local leaders, pooling this huge band of expertise out there of people who have been trying this at the local level — all kinds of lessons learned and figuring out how to do this with transparency.

Instead, that was nixed. AOC is trying to do this off the side of her desk with some pretty huge committees that she has to kick ass on, and Sunrise is building a youth movement. They’re building a youth army, which is great, but I meet people all the time who are like, “I want to be part of the Green New Deal,” and they don’t know how to do it. They don’t see where their entry point is because there actually isn’t an infrastructure saying, “Okay, you guys are going to do this, we’re going to do this, we’re going to figure out what this means to teachers, and you guys are going to figure out what it means to steelworkers,” and come up with an actual plan that is akin to what produced the original New Deal.

But one thing that’s important to remember is that in the period that produced the New Deal and some of the most important legislation, a lot of the organizing happened after FDR was elected and there were a lot of wildcat strikes without unionization, and the institutions were built on the fly. So I take some comfort in that, in reading that history, because I feel like I thought it was different. I thought they were all organized and then they got the New Deal, and I’m realizing that actually a lot of the organizing happened parallel to it, which makes me feel a little bit better.

It’s interesting. I’m so impressed with its rhetorical power — the joining of the social-justice imperative and the climate imperative. I find that for people in the center-left and center-right who are complaining about it, saying this is joining these two missions together in an uncomfortable Frankenstein or whatever, I’m always saying to them that the social-justice stuff is the really popular stuff.

I know, right?

It does seem to me to really quite beautifully stitch together both the challenges and the solutions in a way that is also, when you take it seriously, liberatingly optimistic in the sense that basically everything you might not like about the world is going to be made worse by climate change, but everything you value about the world could be made better by taking action on climate change.

I know. It changes everything. I’ve been trying to make this argument.

What a title. But while it is the case that climate change promises to change everything and that there has been a lot of movement over the past year politically, it’s also the case that things have changed very little to this point when it comes to actual policy and emissions.

There’s no doubt that taking climate change seriously decimates the entire neoliberal project because you can’t have a laissez-faire attitude, where it’s having your emissions in 11 years; you actually need to regulate your way out of it. And yeah, you can have a few market mechanisms in place, but the market is not going to do it for you. You need massive investments in the public sphere, and it’s actually kind of a pain in the butt that we sold off so much of the public sphere.

But it is a bigger challenge to the left. We’ve largely been having battles over the redistribution of the spoils of extractivism — whether we’re going to share them equitably. But whether we can continue to have economic growth and economic extraction is not something the left has really reckoned with.

What do you think about that? Do you think we should diminish our expectations for growth in adjusting to a climate future?

I think we need a very different economy. The centrality of consumption in our economy absolutely has to change. There are areas of our economy that can grow, but they’re not going to be the ones that are all about consumption until we have to think about a different kind of economy and a different measure of happiness and well-being. There are areas where we’re going to have to contract, and I think we’re pretty much still in the stage where we’re talking about all the things we’re going to add but not the things we’re going to subtract.

I understand the political arguments for that, but there’s no question that there are risks. There are ways you can do a Green New Deal that would increase emissions — you’re talking about huge infrastructure investments we need to make, but we have an economy built on fossil fuel, so to make huge infrastructure investments, you’re going to burn a lot of fossil fuels.

Pouring some cement.

But I think the significance of the Green New Deal is that it moves the discussion to how we are going to change our economy. We have to have a conversation about a different kind of economy and economy-wide transformation, not a single policy silver bullet.

And from there, I think we will refine and improve. I think there has to be a built-in carbon audit so that this is rolled out in a way where we keep ourselves honest and we admit that there’s a real risk, a Green New Deal carbon bubble, and that we are going to make sure we don’t do that by auditing how much carbon we’re burning as we’re going and handing that over to the leading emissions-reduction experts and course-correcting as we go.

I think the lessons of history on this are that we don’t need to have figured everything out before we start. I think we need to get the scale of the transformation right and the conversation right, that we are talking about changing how we live; we’re talking about changing our economy.

Which to me is so powerful because the world is going to be changed. The question is, Do you want it to change in this way that is going to be really ugly, or in this way that is maybe not perfect but quite a bit more hospitable?

This is part of why I think we need to also have an honest conversation about how threatening climate change is to the cult of centrism and incremental reformism. A lot of journalists built their identity around being the guy who splits the difference, doesn’t get too excited; that’s how you define your seriousness, right? But it is profoundly unserious at this point to define change in that way, because it means you haven’t reckoned at all with the science, which says our future is radical. The present is pretty radical too. The idea that there is some sort of gradual, incremental, let’s-split-the-difference pathway to respond to this crisis is silly at this point. We may have personal preferences for that, but that doesn’t turn it into a reality just because we want it.

My own general perspective on this is that just about everything seems to be moving in the right direction except time, which is moving in the wrong direction.

You mean in terms of polling?

Yeah, political engagement. More people are more concerned — 75 percent or more believe climate change is happening. A majority of Republicans want “aggressive American action” to combat it, whatever that means.

So are you more optimistic than when you wrote the book because you’ve been out there talking to people?

I turned in the manuscript last September when really none of the mobilization we’ve seen had started. I hadn’t heard of Greta Thunberg at that point; she had barely started her climate-striking. Extinction Rebellion hadn’t begun. I hadn’t heard of Sunrise. And renewables are getting cheaper and cheaper — there’s that to be excited about too. But when I think about really taking seriously the U.N. timeline and the idea that we have to have emissions by 2030, I don’t see any way that’s possible. Do you?

Globally?

Yeah.

Yeah. It is a moon shot, but I do think there’s a scenario where there could be a candidate who makes it the center of their campaign, which I don’t think anyone really has. You have a lot of candidates who endorse the Green New Deal, but I think if we had a presidential candidate who both made the Green New Deal the centerpiece of their campaign and was truly up for the fight of their lives in terms of taking on the corporate interests that would be really against it — and you had sectoral organizing that was ready in 2021 with both plans for what the Green New Deal should mean and the different sectors organized enough to put pressure on the administration. The original New Deal rolled out in nine years, and it did a hell of a lot. They planted more than 2 billion trees. That’s one of the things we have to do.

Did you see that Ethiopia planted 350 million in one day last week?

I didn’t see that. I do think there would be a catalyzing effect for the U.S. to decisively lead. It would change the game a lot in a lot of different countries. I think our chances are slim, but I also think anything big we do is significant. I don’t see this as either we do it all or we should all just give up and drink ourselves to death. I think it all matters because every quarter-degree is hundreds of millions of lives, if not more.

And the centrality of marrying climate action to building a more humane society is all the more important if we don’t do it. In the sense that if we become a society that actually doesn’t let people drown in the ocean and die in the desert and we actually do our damnedest to save lives and believe that people have a right to health care by right of being alive and open up our borders in the face of a massive humanitarian crisis — if we become a society governed by those types of values that are based on valuing and cherishing human life, that will serve us very well if it turns out we were pretty far off the mark in emissions reduction. The rockier the future is, the more important it is that we become a decent society, which we’re not right now.

You mentioned the New Deal as a historical analogy. But you also write in the book about how basically historical analogy is now actually inadequate and that what we’re dealing with is a challenge of a different scale.

It’s not necessarily a challenge of a different scale, in the sense that the speed of the transformation of the economy during the Second World War was pretty much on the scale that we’re talking about. But it’s a different quality, right? I’ve never really been comfortable with military analogies because I actually think we need to make peace with the planet and not militarize our approach to it. I think we have a military approach to the natural world, that it’s all been about containing it. So the idea that we’re going to wage war on climate change — I think we need a different way of living on this planet, and that it’s a lot less militaristic.

But we do have precedents for an incredibly rapid change. That’s why I think there’s never going to be an exact historical analogy, but there are things to learn from all of them. It’s interesting how much public transit people used during the Second World War. It’s interesting that people planted vegetable gardens, and it’s important to remember that during the Great Depression they were also dealing with an ecological crisis with the dust bowl. But I think the main reason to talk about historical analogies is that the greatest baggage we carry from the earlier periods is the feeling of futility and the feeling that we can’t do anything because we’re all so selfish anyway.

Or that only the private sector can deal with anything.

But humans are capable of being many things. We’ve all grown up in an era when we’re told all we know how to do is shop and all we know how to do is gratify ourselves.

People often ask me, “What can I do?” I think really what they mean is “What can I buy”?

Welcome to my world. Now I’m getting us into No Logo.

My brother is an economist, and he’s been doing a lot of research about the Second World War parallels. What he says is they didn’t know they were going to win — what if we lose? But the idea that you don’t start something unless you have a guarantee that you’re going to win is a modern argument.

And modern American.

It’s the definition of defeatism.

We call it the Second World War, but it left a lot of countries out. I think that’s another way in which this is an imperfect analogy. This is such a truly global phenomenon that it requires not just every country but, in a certain way, every person to be participating in the solution. How do you think about that? You mentioned earlier that you think an American president who is quite aggressive won’t really change the game. When I hear conservatives saying, “What does it matter what we do? China is still going to do what they’re going to do,” I understand why that’s a morally grotesque position and an evacuation of our obligations that we have because of our own carbon history and our position in the world. But there’s also a part of me that’s scared by the same problem they’re pointing to, which is just how to organize genuine global action in a moment when the fabric of global cooperation is being pulled apart.

First of all, I think those are different issues, right? “What about China?” has been the excuse all along, and the fact is that China is doing more than the U.S. in terms of renewables.

Although I think they’ve approved six times as many new coal plants thus far in 2019 than they did in 2018.

Until we are in any way living up to our responsibilities, we don’t have any moral standing to push anybody else. If we are, then we do. And I was glad to see that Elizabeth Warren has a link for trade policy on the climate. I think we have to [have one]. We have leaders we don’t use. One of the interesting things about what happens after Trump — if there is an after Trump — is that he has detonated a whole lot of neoliberal shackles around what you can and can’t do on trade.

So at the geopolitical level, how do we organize a path forward?

One of the things I’m struck by is that there are fewer spaces for international strategizing and a sense of cross-border organizing than was the case even ten years ago — but certainly 20 years ago, when you had the World Social Forum in Brazil where there were tens of thousands of people coming together to [see] what can South Africa learn from Brazil. What would it look like to have a global movement that was calling for a different model of trade? We really need that type of international organizing, and we don’t have it right now. The person who is doing most of it is Steve Bannon, and that’s a terrible thing to be quoted saying but it is true and that has to change.

The geopolitical problem scares me more than anything else.

I find what’s happening in Brazil to be scarier than pretty much anything else. It’s also worse thinking about what is happening in Puerto Rico, what is happening right now in Hong Kong. We talk about resistance here, but what is happening in Hong Kong is resistance.

What do you think will happen there?

I’m terrified of what’s going to happen there. But it does show that it’s a reminder of how quickly things can change and that change can be contagious. And what happened in Puerto Rico too, right? I wish it had been amplified more here in the rest of the U.S., because it shows that it’s pretty unpredictable when people have just had enough.

Why do you think there’s more ready energy for protest in places like Puerto Rico and Hong Kong?

It’s really unpredictable. I’ve been around enough years now to have been witness to a few of these effervescent moments, right? And they always come as a surprise. And the tragedy is when they come before we are ready with our alternatives and our ideas. During Occupy, people were like, the whole point is to have no demands, and it’s like, no, we have demands, we have plans, we have ideas, and a new generation of people who are taking the plunge into politics. So I don’t think we’d be in a situation like that if there were an uprising like the kind we just saw in Puerto Rico, like the kind we’re seeing in Hong Kong. I don’t think the U.S. is outside of history, where that couldn’t happen. I think it could. I think so many people are just absolutely horrified and terrified. And if there were one of those tipping points, I think we’d be in a much better situation because of all kinds of plans and demands. So we’ll see.

Do you see the climate strike that’s planned for September 20 as a possible event like that?

I don’t know. I think it’s going to be big, but I think these moments we’re talking about are rarely planned.

So all you can do is get ready for that weird moment, that effervescent moment. I don’t think you can plan what the moment is going to be, but you can plan how not to blow the moment. We’ve blown a few moments, and I would say we’re in a better position not to blow the moment than at any point in my lifetime.

I think you’ve talked about how your real awakening on climate was Katrina. Yet a quarter of all the emissions ever produced in the history of humanity have come about since then.

We’re definitely accelerating.

That was not long ago. An 18-year-old has been alive for a third of all emissions, and I’ve been alive for 55 percent. That’s really fast.

That’s really fast. When I published This Changes Everything, from the environmental movement, people were saying climate change was hard enough — did you have to make it capitalism, did you have to have those in there? A lot of people are more excited about capitalism than they are about climate change. And if everything was going great with capitalism except for climate change, we really would be lucky, but that is not the world we live in.

I think a lot of this honestly is going to get resolved only if we have a different kind of governance. I hate to say it —

You don’t hate to say it! You want a new kind of governance.

I think people still don’t like to hear the idea that government has to lead, that there have to be regulations. People are like, “Well, what can I do?” I can tell you I used to smoke a lot of cigarettes, and I stopped smoking not when somebody told me it was bad for me; I always knew it was bad for me. I stopped smoking when I couldn’t smoke in restaurants and bars and I was outside in subzero weather freezing like an idiot to have a cigarette. And there are going to be things we’re told we can’t do in order to have a habitable planet or some semblance thereof.

More From This Series

- ‘Any Further Interference Is Likely to Be Disastrous’

- ‘We Are Living in a Reality That Is Fundamentally Uncanny’

- ‘The House Is Burning Down and We’re Just Sitting Around Discussing It’

- Do We Need to Abandon Growth to Save the Planet?

- ‘The Long-Term Survival of Our Civilization Cannot Be Assured’