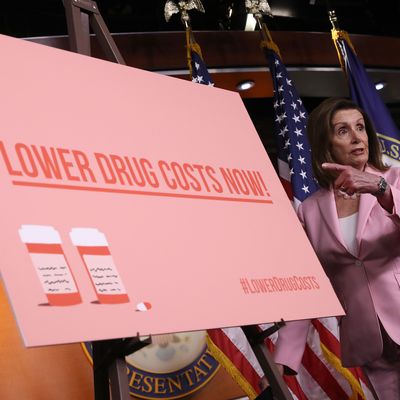

Nancy Pelosi has a plan to score Americans cheap drugs.

On Thursday, the House speaker unveiled her party’s proposal for curbing the skyrocketing costs of prescription pharmaceuticals in the United States by, among other things, enabling the federal government to negotiate the price that Medicare will pay for up to 250 name-brand drugs. Under the terms of the legislation, the Secretary of Health and Human Services would have some discretion over exactly how hard a bargain to drive. But the bill would bar the government from paying any more for a covered drug than 120 percent of the average price at which said pharmaceutical retails in other industrialized countries (specifically, the maximum would be set at 120 percent of the volume-weighted average price in Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, and the U.K.).

Notably, while America’s seniors would be the primary beneficiaries of the legislation, Pelosi’s plan would also lower costs for younger Americans on private insurance: Although the bill would not technically require drug companies to offer the government-negotiated prices to private insurers, firms that refused to do so would face stiff and steadily rising penalties. Specifically, if a company declined to offer Aetna the same deal as Uncle Sam on a given drug, it would have to pay the federal government a fine equal to 65 percent of its gross sales of that drug from the previous year. If the company persisted in its intransigence, the percentage on that fine would increase by 10 percent every three months until it hit a maximum of 95 percent.

The plan would also establish a $2,000 out-of-pocket maximum for Medicare beneficiaries, penalize drug companies that raise the price of their wares faster than inflation, and reinvest the money Medicare saves through negotiation into research for new treatments at the National Institutes of Health.

Although still less far-reaching than progressives would prefer, Pelosi’s bill represents a partial concession to her caucus’s left flank. An earlier version of the legislation would have made the independent Government Accountability Office the final arbiter of a drug’s price, a provision that would have limited the government’s leverage in negotiations.

Unlike the bulk of the House Democrats’ legislative proposals this year, the prescription-drug package is not purely a messaging device. Due the breadth and intensity of public outrage over soaring pharmaceutical prices, along with the popularity of “big government” action for driving down drug costs, some Republican senators have embraced a more modest package of reforms. Meanwhile, Donald Trump has mulled a variety of more radical actions. For these reasons, it’s not inconceivable that some version of Pelosi’s bill could make it into law.

That said, the legislation is designed to serve a clear political purpose: heightening the contradictions between the GOP’s base and its economic orthodoxy. On Thursday, 24 House Republicans decried Pelosi for “pushing a socialist proposal to appease her most extreme members.” But in this case, what’s good for Pelosi’s “most extreme members” is also good for the typical Republican voter. Recent polling from the Kaiser Family Foundation suggests 86 percent of Americans want the government to negotiate lower drug prices for Medicare beneficiaries. And for the GOP’s increasingly elderly coalition, the issue of drug prices is especially salient.

What’s more, by tying the maximum price to an index of what consumers pay for drugs abroad, Pelosi’s bill aims to spotlight the tensions between Trumpian nationalism and corporate conservatism.

Traditionally, conservative economists have had a go-to rebuttal to progressive complaints about the aberrantly high cost of prescription drugs in the U.S.: If Americans paid European-level drug prices, pharmaceutical companies would lack the resources and incentives necessary for sustaining research and development into new cures.

Center-right economists would concede that the status-quo arrangement was unfair. Americans should not have to shoulder the burden of propping up Big Pharma’s R&D while the residents of other OECD countries get a free ride off the resulting innovation. Nevertheless, it was in America’s enlightened self-interest to sacrifice on behalf of the global good, even if other countries took advantage of our largesse. As future Trump White House economic adviser Kevin Hassett wrote in 2004, “The U.S. market has been large enough relative to the rest of the world that it has been able to support research despite [Europe’s] intrusions” into prices — but “there could be devastating effects should our policy environment change.”

This argument hasn’t aged well (and not merely because the case for using monopoly patents to finance drug research is substantively weak). Few nuggets of conservative conventional wisdom are more at odds with Trumpism than “if Europe won’t pay its fair share for drugs, American seniors should pick up the slack.”

And this point hasn’t been lost on Trump himself. Earlier this year, the president contemplated signing an executive order that “would tie some drug prices to those set by European governments, an idea that is tantamount to price controls and opposed by members of his own party,” according to the New York Times. Pelosi has effectively signaled that her party will stand with Trump on this issue even if his own allies won’t.

As of this writing, the White House has yet to take a clear stance on the bill. Where it comes down will say a lot about how the Trump administration balances the president’s political interests against the financial ones of major GOP donors. For the president, signing popular bipartisan legislation that makes good on one of his 2016 campaign promises — and delivers a clear and significant benefit to a core Republican voting bloc — should be a no-brainer. There is only an electoral upside to such a move. Trump doesn’t need Big Pharma’s money, and anyway, what’s the drug industry going to do, start funding the party of single-payer? The only thing that could stop Trump from getting onboard is his conservative advisers’ mindless ideological opposition to interference with the “free market” (which, in this case, is defined as “government-granted patent monopolies”).

Regardless, Pelosi’s bill should secure Democrats a victory of some kind. The question is whether it’ll be a substantive or political one: Either Democrats save American consumers a bunch of money, or they’ll gain their 2020 nominee a potent wedge issue.

For the GOP, actually doing something to help its nonaffluent constituents may be the tougher pill to swallow.