Never before have I seen Democratic candidates do so much to woo workers and win over union leaders. Elizabeth Warren kicked off her campaign at the site of the famous 1912 Bread and Roses textile strike in Lawrence, Massachusetts. Julián Castro marched in Durham, North Carolina, with fast-food workers demanding a $15 wage, while Pete Buttigieg spoke outside Uber headquarters in San Francisco alongside drivers demanding to be considered employees. Joe Biden held his first official campaign event at a Teamsters union hall in Pittsburgh. Kamala Harris has called for a raise averaging $13,500 for the nation’s schoolteachers, while Bernie Sanders has bolstered labor’s cause by using his email lists to urge supporters to join union picket lines.

Why all this sudden attention and affection for workers and unions — far more than I’ve ever seen during my nearly 25 years of writing about labor? Part of it is that this year’s Democratic candidates are doing what any smart politician would do when the field is so large — court one of the party’s largest constituencies, i.e., unions and their members. Part of it is that the candidates see that something is seriously broken in our economy: that income inequality, corporate profits, and the stock market have all been soaring while wages have largely stagnated for decades. Also, Democrats realize that a big reason Hillary Clinton lost in 2016 was that she didn’t show enough love to labor. The field seems to recognize that if a Democrat is going to win the presidency in 2020, the surest route is to win back the three longtime union strongholds — Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin — that were key to Donald Trump’s victory. So the candidates have loosed a flood of pro-worker ideas, not just to make it easier to unionize, but to extend paid sick days and family leave to all workers, provide protections to pregnant workers, and safeguard LGBTQ+ Americans from discrimination on the job.

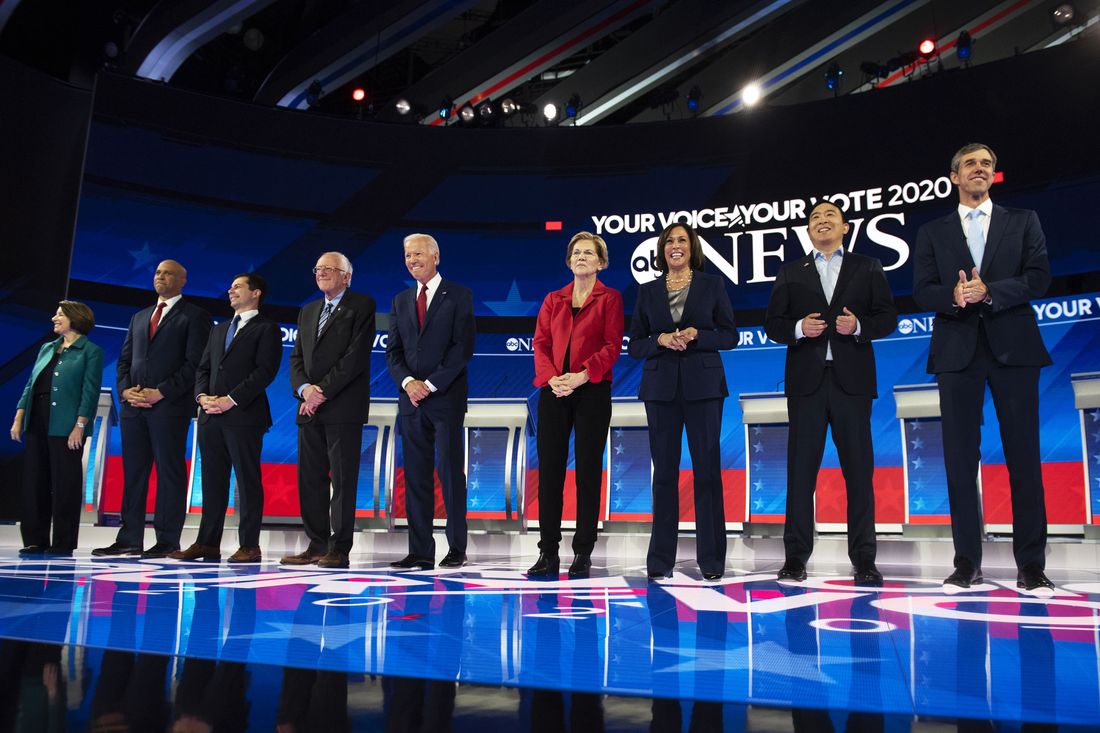

Four of them — Bernie Sanders, Beto O’Rouke, Pete Buttigieg, and Cory Booker — have put forward remarkably detailed platforms of pro-worker and pro-union proposals, while Elizabeth Warren’s elaborate plan on trade goes far beyond what many union leaders have called for. Andrew Yang says his universal basic income will be a boon for workers, providing a lifeline to those who lose their jobs because of artificial intelligence and robots. Biden has been vague so far on labor matters, calling himself a union man and saying he supports a $15 minimum. Booker has introduced a fairly radical bill, the Worker Dividend Act, which would require corporations that do stock buybacks to pay out to their employees a sizable chunk of the money going to the buyback.

Considering how many candidates there are and how many proposals and speeches they’ve made, it’s hard to keep track of who stands for what — and which plans are substantively the most pro-labor. Below, I give grades to the Democratic front-runners, based not just on the positions they’ve espoused during the campaign, but also on their track records. (Some candidates seem to have discovered the cause of workers only after announcing that they were running for the presidency.)

I confess to one bias in grading the candidates. In my new book, Beaten Down, Worked Up: The Past, Present, and Future of American Labor, I write that union power and worker power in the U.S. have fallen to their weakest point since World War II, and that this has fueled wage stagnation, out-of-control income inequality and a warped political system in which corporations and billionaire donors have far too much sway and workers far too little. In grading, I give extra points to candidates who are pushing or proposing strategies to fix this systemic problem and give American workers more power — in the workplace, in politics, and in policymaking.

Some will complain that the grades I give are too high, but it is important to remember that when it comes to worker issues, every Democratic candidate is head and shoulders above almost every Republican lawmaker. Republicans overwhelmingly oppose a higher minimum wage and basic protections like paid sick days, seeming to dread displeasing corporate donors and lobbyists. Most Republicans favor weakening labor unions, not strengthening them. Moreover, the AFL-CIO, the nation’s main labor federation, has given the Democratic candidates’ high scores for their career legislative records: Cory Booker (100), Kamala Harris (100), Bernie Sanders (98), Elizabeth Warren (98), Julian Castro (96), Amy Klobuchar (95), Beto O’Rourke (94). Of the candidates, Joe Biden has the lowest AFL-CIO score (86), based on when he left the Senate in 2009. Some labor experts say that in the highly polarized Congress, in which Republicans are often seeking to undermine unions, it’s not hard for Democrats to garner high AFL-CIO ratings. Still, this year’s progressive crop of candidates supports many bills that would go far to help union and workers, like the Protecting the Right to Organize Act, which would make it easier to unionize, and the Healthy Families Act, which would require most companies to provide full-time workers with seven paid sick days a year.

A

Bernie Sanders

Sanders has fought for workers ever since he entered Congress in 1991, introducing the Workplace Democracy Act in 1992, and reintroducing it in every Congress since. That bill would make it easier for workers to unionize by, among other things, giving them a right to do so as soon as a majority of workers sign pro-union cards rather than through a lengthy election process that strongly favors employers.

Sanders didn’t suddenly start joining union picket lines this year. In 2015, he marched alongside Verizon workers as well as workers picketing outside their potato-starch factory in Cedar Rapids. Sanders told those workers in Iowa, “We are sick and tired of the war against working families.” In this election cycle, Sanders has already won the endorsement of the United Electrical Workers, a small union with 35,000 members.

The labor platform that Sanders has announced this year envisions doubling union membership in four years. It is a dream list for the nation’s unions. Sanders wants to strengthen workers’ clout through legislation that promotes industry-wide bargaining (instead of employer-by-employer bargaining). He would prohibit awarding federal contracts to companies that pay less than $15 an hour; he would also ban right-to-work laws, allow all government employees to unionize, and prohibit employers from permanently replacing workers who go on strike. In perhaps his most radical proposal, Sanders calls for ending America’s at-will employment system — he would prohibit employers from firing workers except for “just cause.”

Sanders’s platform for a Green New Deal has helped lead the way in reassuring unions upset with climate-change activists; he has called for a “just transition” for fossil-fuel workers who lose their jobs if and when the nation shutters coal-fired power plants and takes other actions to slow global warming. Sanders would guarantee those workers five years of current salary, housing assistance, job training, health care, pensions support, and “priority job replacement for any displaced worker.”

Sanders has loudly opposed free-trade agreements. His repeated calls for Medicare for All have cheered many workers and some labor leaders, even as Joe Biden has attacked Medicare for All, saying it would take away the excellent health coverage won by many unions.

Sanders’s supporters argue that he has long been the most pro-labor of the candidates, but others point out that for all his pro-worker rhetoric, he has racked up few concrete victories for workers. Sanders counters that he has led the way on, for example, legislation protecting IBM workers’ pensions and doubling home-heating assistance to help low-income workers. Sanders has been Congress’ most outspoken champion of a $15 minimum wage, and is often given credit for helping persuade Jeff Bezos to boost the base wage at Amazon to that level.

A

Elizabeth Warren

Warren doesn’t have a pro-labor record stretching back decades, but she has been a remarkable fount of innovative, pro-worker ideas. Some union officials told me that her proposal on trade was by far the best and most sophisticated they’ve ever seen from a lawmaker. Criticizing the U.S. for long pursuing “a trade policy that prioritized the interests of capital over the interests of American workers,” Warren has proposed using trade agreements as a tool “to force other countries to raise the bar on everything from labor and environmental standards to anti-corruption rules.” Asserting that corporate lobbyists have long whispered into the ears of our trade negotiators, Warren has called for a far more transparent process and proposed that worker, environmental, and consumer representatives sit on committees that advise America’s trade negotiators.

Warren’s “Plan for Economic Patriotism” is far more thoughtful than anything Trump has developed to encourage and bring back manufacturing jobs. She calls for leveraging federal R&D to spur investment and job creation, noting that Apple has used technologies developed through federally sponsored R&D to produce tens of millions of iPhones overseas. To aid depressed communities, Warren says, “R&D investments should be spread across every region of the country, not focused on only a few coastal cities.” To boost the job prospects of young Americans who don’t go to college, she has proposed a tenfold increase — a total of $20 billion over ten years — for apprenticeship programs.

In a daring proposal, Warren’s Accountable Capitalism Act would give labor far more voice in the economy by letting workers elect 40 percent of the board members of large American corporations. Her path-breaking work to create the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau has been a boon to working families, helping prevent banks from imposing extortionate fees and helping keep payday lenders from preying on down-on-their-luck workers.

As Blue Compass, a political and opposition research firm, makes clear, week after week Warren has done far more on social media than other candidates to go to bat for unions, for instance, doing videos on behalf of Las Vegas hotel workers seeking a contract. Amid concerns that Medicare for All might hurt some union members, Warren has pledged to include labor leaders in all Medicare for All discussions. “Strengthening America’s labor unions will be a central goal of my administration,” Warren told In These Times. She recently won the endorsement of the Working Families Party, which had endorsed Sanders in 2016.

Last Monday, at her rally in Washington Square that attracted 20,000 New Yorkers, Warren spoke movingly and at length about the 1911 Triangle Fire, about the 146 Triangle workers who died, and about the brilliant efforts, led by Frances Perkins, who later served as Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Secretary of Labor, to prevent more such factory disasters — and to improve conditions overall for America’s workers.

B+

Pete Buttigieg

Mayor Pete’s platform on labor, A New Rising Tide, is one of the very best things I’ve read from any modern-day politician on worker issues. He sees much injustice in the workplace: that Uber misclassifies workers as independent contractors to deny them basic worker protections, that the McDonald’s franchising model undermines workers’ ability to unionize, that Google hires so many temps and independent contractors to undermine workers’ bargaining power. “The hard truth is that while the economy changed, workers’ voices” have been “systematically silenced,” Buttigieg writes. “Our economy has been tilted towards the wealthy and away from the middle and working class because the people in power designed our laws and policies that way.”

Buttigieg’s platform would raise the federal minimum wage to $15, end right-to-work laws, give workers the power to unionize through card check, guarantee paid sick leave and family leave, ban the use of permanent replacement workers, and take strong steps to curb corporations’ often-intimidating sway over unionization elections.

Union officials in Indiana say that Buttigieg, though just 37, is not a Johnny-come-lately in supporting labor. He sided with labor unions when Indiana Republicans sought to repeal the state’s “common construction wage law,” which helped assure higher wages for construction workers. Buttigieg also signed a labor-backed “responsible bidding” ordinance that requires businesses seeking city contracts with South Bend to disclose OSHA violations.

“He’s been fantastic,” Jim Gardner, an official with the Operating Engineers union told In These Times. Buttigieg’s unsuccessful campaign for state treasurer in 2010 was run out of the offices of South Bend’s building trades unions.

B

Joe Biden

Biden was the first candidate to secure a union endorsement, receiving it from the 320,000-member International Association of Fire Fighters. Its longtime president, Harold Schaitberger, lavished praise on his friend, saying, “He’s one of the staunchest advocates for working families. He knows that a strong middle class means a strong America.”

Nonetheless, Biden faces many questions from unions. He voted for the North American Free Trade Agreement, and while President Obama was considered pro-union, he negotiated the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade agreement. Biden supported that agreement, and many unions deride it to this day, even after Trump pulled out of the agreement.

At his campaign’s official kickoff event at a Teamsters hall, Biden trumpeted, “I make no apologies. I am a union man.” Some union leaders were nonetheless upset that on the day Biden announced his candidacy — three days before the Teamsters hall event — he spoke at a high-dollar Philadelphia fundraiser organized by a senior executive at Comcast. Patrick Eiding, the president of the Philadelphia AFL-CIO, complained that the “first place he goes” is to a Comcast executive’s. “No connection with labor,” Eiding said. “It was a little disturbing.” One labor scholar, writing in May, said he could find only two instances when Biden appeared on a picket line, “once in Iowa, during his 1987 presidential campaign and just this month (May) in Boston,” backing the Stop and Shop supermarket strikers.

As a senator, Biden supported organized labor’s No. 1 priority, the Employee Free Choice Act, which would have made it easier to unionize by, among other things, giving unions a right to use card check. At a forum sponsored by the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees in August, Biden spoke robustly for labor, decrying “an all-out war on suppressing wages to increase profits.”

The labor platform that Biden has sketched out so far is short, indeed abbreviated. He supports a $15 minimum wage, curbing noncompete clauses, easing occupational licensing requirements, and making it easier for workers to unionize and bargain (without spelling out how). None of this is the fight-like-hell stuff one might expect from someone who characterizes himself as a champion of labor.

B

Cory Booker

Booker has pushed some daring, unorthodox ideas to help workers. One is the Worker Dividend Act, a Senate bill he sponsored that would help workers share in a company’s profits by requiring corporations that do stock buybacks to pay their employees either an amount equal to the lesser of the value of the buyback or half of all profits above $250 million. Booker has also proposed a job guarantee that would give 15 cities or rural areas federal money so they can guarantee jobs to everyone who wants one. Economists say this pilot measure would go far to help marginal, struggling workers.

Booker has a reputation for being close to Wall Street — he defended Bain Capital when Barack Obama attacked it during the 2012 campaign, and received $2.2 million from the securities and investment industry, more than any other senator, during the 2013 to 2014 election cycle. Nonetheless, his record on worker rights and unions is progressive — he backs a $15 minimum wage and bills that would make it easier to unionize, including Sanders’s Workplace Democracy Act and the Protecting the Right to Organize Act. Last Wednesday, Booker beefed up his labor bona fides by releasing an elaborate platform called “Opportunity and Justice for Workers.” In it, Booker says, “For most people in this country, our economy is broken.” His platform calls for sweeping new laws to make it easier to unionize, raise workers’ wages, and ease work-life balance.

Teachers’ unions have long been uneasy with Booker because he championed vouchers and charter schools as Newark’s mayor. Labor leaders complain that these moves siphon money from traditional public schools and undermine teachers’ unions. The Newark Teachers Union opposed Booker’s 2010 reelection as mayor. But Booker argues that that teachers’ union often obstructed moves to improve educational quality in Newark’s struggling schools. At a union forum in August, Booker said he would prioritize public schools and noted that the New Jersey Education Association, his state’s largest teachers’ union, had endorsed him as a Senate candidate.

B

Julián Castro

Castro has been the most outspoken candidate on behalf of immigrants, but his platform has been thin on worker and labor issues. (Vox’s labor reporter wrote that Castro “probably has the weakest labor platform” on worker issues.) He met with striking University of California medical workers and attended a meeting of campus workers at Stanford, his alma mater, to show support before they began contract negotiations with the university. (California’s early primary is especially important for Castro’s prospects.) He has spoken at various union audiences, but he hasn’t made lifting up workers a central theme of his campaign. Castro backs numerous measures that would help working families, including universal child care, paid family leave, and a $15 minimum wage.

B

Kamala Harris

Unlike Sanders, Booker, Buttigieg, and O’Rourke, Kamala Harris has not adopted a plan that shouts to the world that she is eager to expand unions. She has taken a different, sometimes innovative course. She has trumpeted a plan that would lift the pay of the nation’s public school teachers by $13,500 on average, a move that has delighted two of the nation’s largest and most powerful unions: the National Education Association and the American Federation of Teachers. In July, Harris introduced legislation for a National Domestic Workers’ Bill of Rights, which would help the nation’s nannies, housekeepers and caregivers by giving them minimum wage and overtime protections and paid time off and requiring their employers to give them written employment contracts. To reduce income inequality, Harris has introduced a bill called LIFT the Middle Class Act that would give a refundable tax credit of up to $6,000 a year to households earning under $100,000 annually.

Harris uses social media to promote various union causes, such as organizing UCLA’s medical residents. But she has not made battling for unions and workers a signature part of her campaign the way Sanders and Warren have and has not issued a detailed labor platform.

B

Beto O’Rourke

O’Rourke’s labor platform, A 21st Century Labor Contract, is an impressive, thoughtful document. He calls for lifting workers collectively by expanding unions and their bargaining clout, while also calling for lifting workers individually, legislating new worker rights, by, for instance, guaranteeing seven paid sick days.

In his labor platform, O’Rourke proposes a nationwide law to let all government workers and farm workers unionize, and doing likewise for all frontline supervisors and independent contractors. (Letting frontline supervisors join unions would greatly expand union power, especially during strikes; letting independent contractors unionize and bargain would be a powerful tool for gig workers.) O’Rourke would adopt nationwide rules making it far easier for Uber and Lyft drivers and other gig workers to be considered employees — a move that would extend minimum wage and overtime coverage to them as well as protections against sexual harassment and race discrimination. O’Rourke would establish government-appointed wage boards that would set, and presumably improve, wages and conditions for industries with low union membership — for instance, fast-food restaurants, nail salons, carwashes.

Although from conservative Texas, O’Rourke has forcefully called for raising the minimum wage to $15 so workers don’t have to juggle two and three jobs. Some labor advocates point out, with chagrin, that when O’Rourke was on the El Paso City Council in 2010, he questioned whether police and firefighters should have a right to bargain collectively. At the time, El Paso faced a large budget deficit due to the recession, and city officials wanted municipal unions to agree to defer their raises. O’Rourke was angry that the police union continued to insist on wage increases that he said amounted to 8 percent. At one point, O’Rourke even asked the city’s attorney whether there was a way to eliminate the police union. In a 2011 interview, he said, “I do not think it is in the community’s best interests, certainly not in the taxpayers’ best interests, to have collective bargaining by the police and firefighters.”

But more recently, O’Rourke has championed the right of all public-sector workers, including police officers to unionize, telling a union meeting in Houston in July, “We’ve seen the devastation in our communities and in our states when unions are not allowed to organize … As president, I want to make sure that we guarantee the right to organize for every educator and public servant in every state.”

B-

Amy Klobuchar

Klobuchar has “one of the vaguest labor platforms” of the Democratic candidates, Vox wrote recently. She often tells audiences that she is the daughter of a unionized teacher and newspaperman and granddaughter of a unionized iron ore miner. She says that “as President she’ll stand up against attempts to weaken unions,” adding, without offering details, that she wants to reform labor laws, protect collective bargaining rights and roll back right-to-work laws. In her first 100 days as president, she says, she will issue executive orders requiring federal contractors to pay at least $15 an hour, scrapping Trump’s rollback of overtime protections, and banning companies from requiring low-wage workers to sign noncompete clauses.

Despite her impressive rhetorical and debating skills, Klobuchar is not much of a fighter for workers — her focus is usually elsewhere — and this from a lawmaker whose state has a famous farm-labor tradition and has sent several warriors for workers to the Senate, most recently Paul Wellstone. Some former Klobuchar aides have said she can be an abusive boss. Based on interviews with ex-staffers, The New York Times wrote that Klobuchar was “not just demanding but often dehumanizing” and “not merely a tough boss,” but “the steward of a work environment colored by volatility, highhandedness and distrust.” Considering this, that’s all the more reason Klobuchar should be working doubly hard to show she is a champion of workers.

C+

Andrew Yang

Yang talks as if his universal basic income program (which would guarantee $1,000 a month to every citizen over the age of 18) would be a boon for America’s workers. He says it would be a welcome supplement for low-wage and part-time workers and a lifeline to laid-off workers, helping them avoid misery and easing the pressure on them to take whatever job is offered them, no matter how low the pay. He says UBI would increase workers’ bargaining power “because a guaranteed, unconditional income gives them leverage to say no to exploitative wages and abusive working conditions” UBI would help workers who are on strike, Yang says, by enabling them to hold out longer and demand a better contract.

To my mind, Yang’s single issue — Yang calls it a “Freedom Dividend” — hardly begins to address, much less fix, the biggest problems American workers face: soaring income inequality and the overall decline of worker power. Some experts argue that UBI would encourage some employers to lower workers’ pay.

In a Labor Day blog post last year, Yang seemed to have only just discovered the importance of labor unions and collective worker action — he was marveling at the historic achievements of Walter Reuther, the UAW, and other unions, and how they played a pivotal role in building the world’s largest and richest middle class. In Yang’s platform, there is little acknowledgement of what collective action or unions have achieved and can achieve for American workers. (He inaccurately says union membership has dropped 70 percent from its peak; it’s dropped 30 percent.)

Many people I respect support UBI, especially to help the millions of workers who some predict will lose their jobs because of AI, robots, and other new technologies. I nonetheless wonder how will laid-off workers survive on $12,000 a year, especially when some supporters of UBI have called for weakening various parts of the social safety net. As far as I can tell, Yang — who is very eloquent in discussing the threat that new technologies pose to workers — has hardly discussed a key issue: the importance of giving workers (and not just corporate executives, technology gurus, and Silicon Valley investors) a voice in what new technologies will mean for workers and the economy. I fear that UBI, combined with technology-induced layoffs, will create an underclass of the long-term unemployed scraping by on $12,000 a year, and an overclass of very wealthy executives and investors who own and control the new technologies.

F+

Donald Trump

Trump campaigned as a champion of workers, but his administration is unarguably the most anti-worker, anti-union administration since Ronald Reagan — and is arguably even more anti-worker. Trump and his appointees have taken dozens of actions to hurt workers. They have rolled back overtime protections extended to millions of workers and scrapped the “fiduciary rule” requiring Wall Street firms to act in workers’ best interests in handling 401k’s. His administration has reduced the number of OSHA inspectors and weakened safety requirements for oil-rig workers. Trump has made it easier to award federal contracts to corporations that have repeatedly violated minimum wage and overtime laws, race and sex discrimination laws, and laws protecting workers’ ability to unionize. His administration has hurt LGBTQ+ workers by urging the Supreme Court to rule that they are not covered by federal anti-discrimination laws.

Trump’s nominee for Secretary of Labor, Eugene Scalia, has long been corporate America’s top gun, its leading lawyer, in seeking to quash many new regulations protecting workers. Trump’s Supreme Court appointee, Neil Gorsuch, provided the pivotal vote in important cases that weakened public-sector unions and let corporations prohibit workers from bringing class actions, making it far harder for millions of Americans to vindicate their workplace rights. Trump’s appointees to the National Labor Relations Board have been extremely aggressive in seeking to weaken unions and obstruct union organizing – for instance, declaring that Uber and Lyft drivers shouldn’t be classified as employees, making it far harder to unionize franchises like McDonald’s, and vastly reducing the ability of contracted-out workers to picket employers.

The only reason Trump deserves an F-plus and not an F is that he had made good on one big promise to workers — his vow to fight on trade. He has pushed to revamp NAFTA and confront China. But in renegotiating NAFTA, Trump failed to do the one thing labor unions said was most needed: to make sure that NAFTA’s enforcement mechanisms had teeth so that Mexican workers could push for higher wages and to unionize without being suppressed or jailed.

Moreover, Trump has hugely mishandled his trade war with China. Any child can tell you that if you’re going to pick a fight with a powerful adversary, you want your friends lined up at your side. But Trump launched his trade war against China, the world’s second largest economic power, without getting important allies like Canada, the European Union, Japan, and Australia to fight along with us. As a result of Trump’s unilateral trade war, China is feeling much less pressure and America’s workers, farmers, consumers, and corporations are getting battered. Trump deserves a failing grade for the way he has so badly bungled his trade war.

Steven Greenhouse was the New York Times’ labor and workplace reporter for 19 years and is author of the book Beaten Down, Worked Up: The Past, Present, and Future of American Labor.